(Continued from my previous posts on PRISM.)

Nobody is easy. Almost nobody, that’s the tricky part.

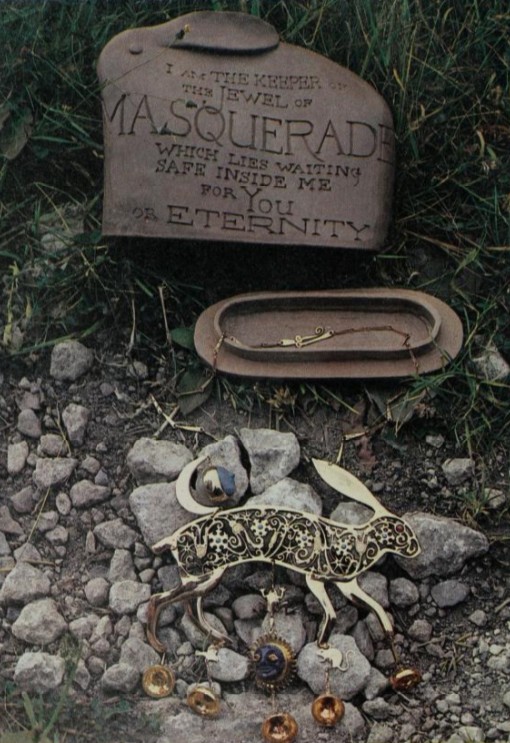

On the night of August 7th, 1979, I set off with Bamber Gascoigne, who was chosen to witness the burial. Once at the right spot, I cut a turf about ten inches square with my knife, then dug down until I’d made a hole to the depth of my elbow. There was a moment of panic when my trowel hit rock, but it turned out to be just a small stone. In went the pot with the gold, then the earth and the turf. I watered the spot to encourage the grass to grow again. As Bamber and I shook hands over the burial ground, the moon came out from behind a cloud and, I like to think, shone down a blessing on us.

— From Masquerade, The Complete Book With the Answer Explained

The grand “thousands (or or tens of thousands, or more) participants / only one winner” treasure hunt seems particularly daunting to manage if it is meant to go over a large chunk of time. It is unclear if Masquerade’s multi-year span was accidental or intentional. Certainly, when Williams designed the puzzles and hid his hare, he fretted over the puzzle being too simple, as explained by the witness Bamber Gascoigne:

Kit had explained to me the basis of his puzzle, but even with that privileged information I was unable to make it work out. The cause of my growing uneasiness was the thought that if it was in fact impossibly difficult, then I was the only person in the world in a position to form that opinion. Kit considered it very possible, even perhaps dangerously easy, because he had invented it.

The game had the right density of red herrings to baffle the public; more than “he had invented it”, I think the reason Williams thought the puzzle was easy is he knew exactly which elements were red herrings. The excess of extra text and riddles (including hiding a hare in every picture) made it easy to project almost any answer whatsoever.

They are far more complex than anything I had imagined, yet they fit the book. It’s a scientific principle that if you want something to work badly enough, you organize the facts so that it does. I watch people allowing themselves to be twisted round and round. In the long run, solving the book is a matter of trial and error.

— Kit Williams quoted in The New York Times, The Legend of the Golden Hare, November 15, 1981, while the hare was still buried

One issue (which applies also to Alkemstone and PRISM) is that the puzzle requires indicating an exact spot. This was long before public GPS use. Even getting somewhere in the ballpark isn’t good enough; a small field is too hard to dig without more information. Williams managed this (possibly with incorrect measurements) by using a particular day and a particular time and the exact position of a shadow. Based on what we know about Alkemstone, I’m guessing a similar idea. With PRISM, I’m not sure; PRISM’s job is made more onerous by having to give the location of three items.

People have been using clues to guess states (and I’ll get to that) but somewhere, somehow, there has to be something at a numerical level. Perhaps it is the shadow trick again (given the product’s theme of light). Is there some other way to do it?

Or it could be the puzzle is broken by unclear directions, like the stereotypical pirate map “forward 50 paces, then right 60 paces” which isn’t very exact at all. I had at least vague concern that this screen might be like that, although there’s a theory from the comments I’ll get to later that treats the puzzle as wordplay.

All this relates to another issue: how close are the keys to each other? There is no rule that says they need to be spread out across different states, and in the review I referenced last week the author asked specifically that question (with no answer received). I could see some particular landmark being marked which then gets re-used three times for three different shadow points, for instance.

I think part of the reason Pimania had a superior puzzle from what we’ve seen so far is it did not require an exact location; it was able to use fairly general symbolic language without getting into the nitty gritty of exactly how many meters forward from spot X to get.

I bring all this up not just because theorizing is part of the point of this blog, but also because it may help in forming a solution. Thinking backwards, we know three exact locations have to be clued somehow. (Maybe in a flawed way, but even the most self-deluded of puzzle-setters would know they can’t just indicate a particular park somewhere.) There’s not a lot of emphasis on time of year (like there was on Alkemstone — which is why I suspect that game was using the shadow method); if a game was not using the shadow method, is there some other compact way to represent three entirely different digging spots?

I note that the majority of the “twisted round and round” answers that I’ve seen referenced for Masquerade fail the criterion of giving an actual spot to dig. (From the NYT article: “Among the most common ‘solutions’ Williams receives are: Stonehenge, the Greenwich Observatory and the Hill of Tara in County Meath, Ireland.” I suppose you could claim you meant the “high spot” of a hill but even that would tend to be ambiguous. To be fair, some of these were sent to the author trying to go “fishing” for information with the hope they’d get feedback that they had the right area, just they needed to refine down to an exact spot.

Swerving back to looking at the actual content, we had various theories trying to interpret the different side messages. Regarding that “In at 7…” message, John Myers had a promising theory:

The word “rerouting” has “out” at position 4, “in” at 7 and means “forward” (as in to forward mail) and is slightly more than 8 letters. No idea how this fits into the puzzle if it is correct though.

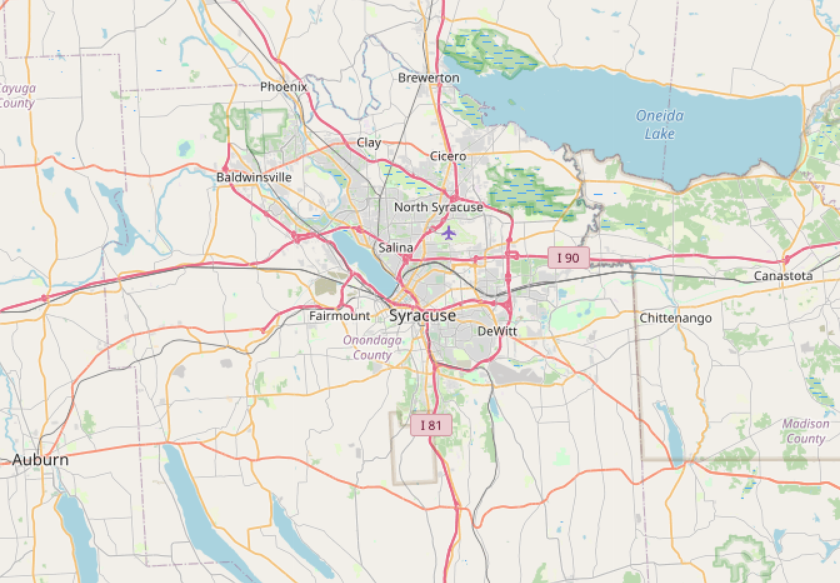

That is, the word being built is _ _ _ O U T I N _ like a cryptic crossword clue. I’m not sure where to go with this information, though; it might suggest US map routes, but not what to do with them. Syracuse is incidentally at the intersection of I81 and I90:

Aula and Aspeon tried to interpret messages as US states:

Also, “TWO OF ONE” comes before “ONE OF TWO” because the only always-sensible reading order is left/top/right/bottom. This makes the text rhyme at the halfway point and end (here TWO/BLUE) with the only exception on the page with “1 THRU 3 / OF EIGHT”. There are several states with eight-letter names, but only in “Oklahoma” all of the first three letters can point to other states; O for Ohio, K for Kansas (34th state, so XXXIV) and L for Louisiana.

“IN AT 7 / OUT AT FOUR / FORWARD 8 / AND SLIGHTLY MORE” is probably cluing South Carolina in a similar way: letters 6-7 of Carolina are IN, letters 2-4 of South are OUT, letters 6-8 of the full name is CAR, and there are a few leftover letters. (S/H/OL/A)

In more expansion of the “maybe some clues indicate states” idea, Rob suggested that “Up north / Lines meet / Down south / Fates greet” was in reference to some kind of state lines (like the “four corners” area around Arizona/New Mexico/Colorado/Utah) and Matt W. though perhaps “Fates greet” could be Truth and Consequences, New Mexico.

Morpheus Kitami tried to organize the letters based on color (using, as Aula points out, the proper order of starting left and going clockwise):

Red: PIMSRNESUHRTTENAREGVIXXX

Blue: RLACENONESRNENUR

Green: GCKFKAEUASVYOLA

Purple: APOLARTFLIE

With anagrams of

Red: PRISM HUES GRANE XXXVI (NRTTE extra)

Blue: CLEAR ONE RUNNERS (N extra)

Green: YOLSVA

Purple: POLAR LIFE

(The green is excluding the “GCKFKEA” text.)

He also highlighted what he calls an “elevator”…

…although I admit I just thought of it as a door with the text over it. Intuitively, I do think there’s a fair chance this is a real clue, perhaps indicating whatever we find will have “west” amount indicated first and then “north” amount after. Or perhaps the up-arrow can be interpreted as a mountain, because there’s a few I Ching symbols scattered throughout, all of them referring to Gen (Mountain).

There’s a similar symbol at the fallen-tree picture. (It could be two versions of Li or Fire stacked on top of each other.)

There’s enough mountain references in the art I got suspicious, but other than my guesswork going nowhere, it was failing the basic question of how do you indicate three exact spots? One could imagine very expensive surveying gear somehow being placed at particular heights but it seems like you’d need to still convey a large amount of information in order to mark where X is.

Even the “mystery anagram” page which is fairly sparse has part of a mountain in the picture.

I’m definitely going to be making at least one more post — I am determined to organize the information into some sort of (likely spectacularly wrong) theory so I can at least encapsulate what the authors may have been up to. More ideas in general are of course welcome.

In the meantime, anyone with a theory on NOT A ROCK, NEVER HOT, NOT FRUIT, NEVER LOCKED? I might throw this one out to social media because it seems plausibly standalone. It doesn’t work like a “riddle” since there are plenty of things that fulfill all four categories, but is there something themed around the contents of PRISM that would work best? Or maybe a set of five things (or more), where four out of the things are excluded neatly by the “rock/hot/fruit/locked” phrases?

You seem to be assuming that (just like in Masquerade) the solution must be contained solely in the pictures and that the pure-text screens are irrelevant. Is there any reason for that? As a first guess it would be more sensible to assume the exact opposite, because there are several possible methods to hide the locations within several thousand characters of text.

I am not assuming but I also have not found anything worth sharing. (Other than “looked redly” being curious.)

I also noted the very regular and symmetric I Ching symbols as especially standing out in the otherwise more chaotic images. And three trigrams (3x trigram 7), each in their own color, matches well with the different locations. Their name (according to English Wikipedia) could be said to be “keeping still” or “bound” and some of their representations are “mountain”, “earth”, “northeast”, “northwest”, “hand”, “resting”/”standstill” and “dog”(!).

Note that I Ching hexagrams have their own meanings, not just a “double” trigram. Again according to Wp this one (hexagram 30) is made up of two “the clinging”/”radiance” (representations including “fire”/”glow”, “south”, “east”, “summer solstice”, “spring equinox”, “eye, “light-giving” and “pheasant”) (seems very fitting with our PRISM and its rays) trigrams (trigram 3) and the combined hexagram is called “radiance”, “the clinging fire” or “the net”.

Do we have any background on how do into I Ching things we could expect the game authors to be?

What is known about the “animated slide” format used? Could the animations (the rays) have been made it off any number of frames per slide, could the order of colors be any order? What are the exact color cycles in all (ray) animations, or are they all the same? Could there be some encoded meanings to find here?

lol I commented on the wrong post.

I was trying to think of landmarks that would match the riddle, and got distracted by the collection of color letters, where “Trent” was “leftover” in one group.

The Big Sioux River has a place called Double River Bend near Trent, SD:

https://www.hmdb.org/PhotoFullSize.asp?PhotoID=342215

I don’t think any guesses have focused on numerical NESW coordinates yet, especially since the text isn’t explicit about numbers in great detail. I include this link as it has the GPS coordinates expressed in the traditional lat/long that are probably more likely (if coded) in the game’s text. 96W/43N for this one.

The Big Sioux flows through multiple states as well, but not sure if that counts as “lines meet.”

In at 7, out at 4, forward 8 and slightly more:

https://www.wilsoncastle.com/

Not sure how the 8 fits into this, but the picture has a castle, and US 7 leads north-ish toward Rutland, VT as US 4 leads away from it.