Archive for September 2016

The Interactive Fiction Competition, or IFComp, is about to start. Unlike previous years, this blog now has a following outside the interactive fiction regulars, hence —

Q: What is IFComp?

IFComp has beeen running since 1995 and was intended to promote short (under 2 hour) interactive fiction. At the time this was synonymous with “text adventures,” although now pretty much anything that qualifies as interactive textual narrative is welcome. (Fret not, adventure gaming fans — a large chunk of entries still fall within the genre.) The first year ran with 12 entries, and this year will be along the lines of 50+. Some games run short and some run long, but I’d say the overall average is an hour per game. That’s over 50 hours worth of content.

The only requirement for entry is that the game be previously unreleased. The public then is welcome to cast votes in the form of ratings from 1 to 10. The judging period lasts from October 1st to November 15th, at which point winners are announced and prizes are allocated. Lots more details are on the website here.

Q: Are you reviewing all of them?

Last year I swore I wasn’t going to, and somehow it happened anyway. This year’s expected to set another record for most entries. I don’t know if a full review set can even be done. (Note to other reviewers: please don’t take this as a dare. Keep your health!)

Q: What’s your judging criteria?

A: I can’t use a rubric without feeling icky; somehow everything feels less pleasant to me if I try to slot it into little categories. I just pick on the most memorable parts, either good or bad, and let the words flow.

I appreciate good characters, good story, good prose, and good gameplay about equally well. Different works set up different expectations. I have greatly enjoyed some IFComp works with very little gameplay and others with almost pure gameplay. As long as the package as a whole makes sense I have a great deal of latitude in what I like.

Q: I’m an author! Can I comment on your reviews?

A: The rules of IFComp now allow public comment, although I will go on record as stating that author comments on public reviews are generally a bad idea. (Sam Kabo Ashwell’s essay here gets into detail.) I’m not turning on moderation just yet, but I reserve the right to filter comments until the competition is over.

However, I am perfectly happy to discuss anything via my email address; you can find it at my About page.

By Andrew Schultz. Played to completion on desktop with Gargoyle.

Confession: I originally put off reviewing this game because I wanted to give it a longer-than-2-hour treatment (judging time during IF Comp is normally limited at 2 hours). I then found out from the author that there was going to be a second release. When the second release came out, I heard about some bugs (with the alternate endings, apparently) and waited a bit longer for version 3, which still isn’t out. However, with IFComp 2016 fast approaching I decided to check the GitHub for the game which has something called “release 3.” I went with that.

The main character, Alec Smart, has just finished rereading The Phantom Tollbooth when he finds a mysterious ticket inside leading to somewhere called “The Problems Compound”. Thus kicks off a surreal series of vignettes with a main objective to find the “Baiter Master”.

Second confession: I also put reviewing this game off because it is slippery. My brain just can’t seem to catch a hold of the prose, descriptions, or most of the characters.

Tension Surface

While there’s nothing here other than an arch dancing sideways to the north, you’re still worried the land is going to spill out over itself, or something. You can go east or west to relieve the, uh, tension. Any other way, it’s crazy, but you feel like you might fall off.

Some mush burbles in front of the arch, conjuring up condescending facial expressions.

Well. You start to feel good about figuring the way out of Round Lounge, then you realize that, logically, there was only one. You remember the times you heard you had no common sense, and you realize…you didn’t really show THEM, whoever THEY are. “Not enough common sense.”

What does a dancing arch look like? How does the land spill out over itself? What do you visualize when you see “mush” with “condescending facial expressions”? What does that third paragraph even mean?

I’ve played other Schultz games without this kind of stress and what feels like roughly equivalent prose. I think what pushed me over the edge here was the wordplay is more of a world feature than a gameplay mechanic; specifically, there are many “transposed word” phrases like “Meal Square” and “Vision Tunnel” that serve as places, people, and things rather than puzzle elements. Strip away all the verbal dressings and there are some very ordinary applications of objects to other objects to solve puzzles, and the language felt more like a burden than a legitimate obstacle.

Speaking of the puzzles: an early part I enjoyed involved collecting 4 “boo tickety” pieces for deviant behavior. There was room for creativity (spoiler example in rot13: Lbh pna trg n obb gvpxrgl sbe gelvat gb qebc lbhe obb gvpxrgvrf) and the overall design advanced the feeling of the world being a coherent whole. Unfortunately, most of the puzzles after veered between too easy and absurdly hard. This may have resulted from the lack of a central consistent puzzle idea. Many involved simply giving the right item to the right person. On the other hand, I wonder if anyone defeated the “thoughts idol” without resorting to the hints.

There was a character that I liked; it is the main character, Alec Smart, who might be the strongest I’ve seen in an Andrew Schultz game.

You’re reminded of the day you didn’t get a permission slip signed to go to the roller coaster park at science class’s year end. You wondered if you really deserved it, since you didn’t do as well as you felt you could’ve.

Small bits of attitude here and there permeate the game. Alec is nervous and smart and socially awkward in ways that feel natural and real.

[1] Boy howdy! This sure is an interesting place!

[2] For such an interesting guy, you sure have nothing better to do than stand here and block people going north.

[3] Can you let me north? Please?

[4] Um, later.

> 2

You’d like to say that, and someone with more courage can, but you can’t right now.

This is made doubly stark by the presence of a “cheater section” of foods Alec can eat that will change his personality. For example, “greater cheese” makes him bolder…

You manage to appreciate the cheese and feel superior to those who don’t. You have a new outlook on life! No longer will you feel bowled over!

…and you can just stroll to the “ending” from here, but this isn’t the most positive outcome. Despite small tweaks in personality making things easier, it’s clear Alec should be able to succeed just as he is. I think this game’s problems with rampant surrealism might have been mitigated by just letting Alec have a stronger voice, grounding events in ways that reflects the real world.

Third confession: I am fairly certain I am not doing this game justice. There are, according to the documentation, a lot of alternate solutions and branches. There is a command (“BROOK BABBLING” or “BB”) which will let you shorten conversations to just essential facts. As weird as it comes out, there was clearly a lot of thought to the character design. Possibly I am the wrong person to pry open all of this game’s secrets.

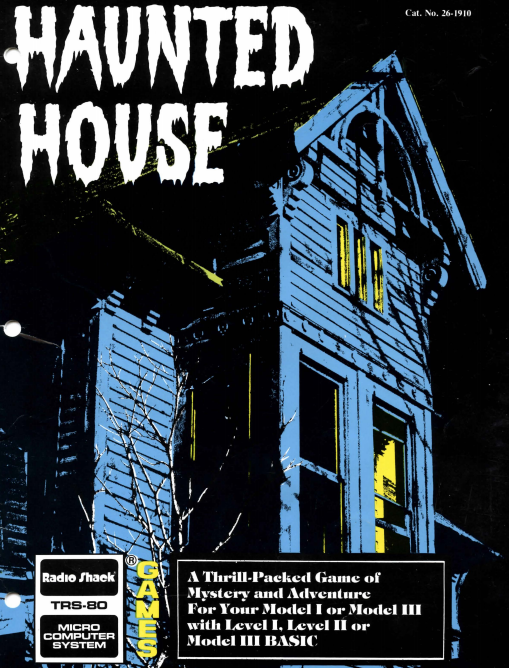

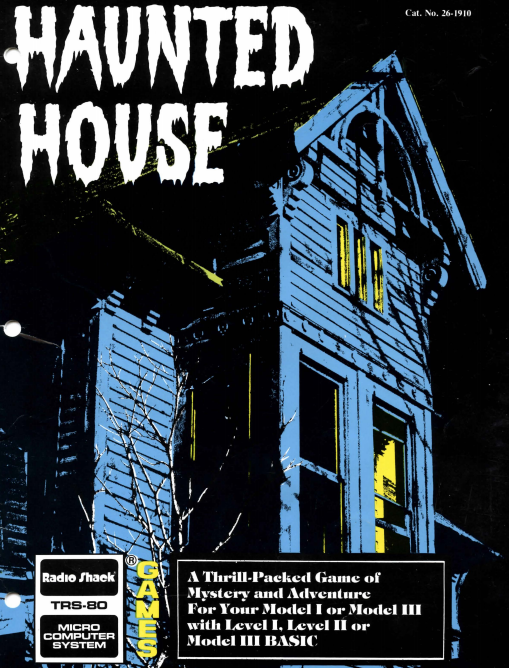

Last I visited Haunted House I thought I was done playing. Fate decided otherwise.

Before I go on, I want to preface: this game was written with *very* tight requirements. The TRS-80 was originally released with only 4K of memory space, and while the base model was swiftly upgraded to 16K it appears Radio Shack wanted Haunted House be playable on any of their systems, including the lowest end models.

Hence, the entirety of this game fits on two 4K cassette tapes, and not for a total of 8K; each cassette is a self-contained part of the game. For reference, Adventureland (which is legendary for extremely tight space requirements) uses the entire luxurious 16K of the newer model (that is, four times the size).

So in a way Haunted House is an impossibility, a marvel. It is still a deeply bad game.

We left off on holding a bucket of water, with no apparent way to apply it to a fire.

You can “pour bucket” but it just pours water on the ground and refills. Would you suspect a bucket of endless water is a useless red herring? (Well, maybe Joseph Nuccio would.)

I want to stop for a moment and emphasize you can walk through the fire without carrying the bucket of water. The bucket of water is entirely unnecessary and its entire existence seems to be very specifically engineered to force players into an intentionally impossible game of guess the verb. Perhaps this doesn’t sound so frustrating with me just describing it, but I assure you in terms of actual gameplay this is possibly the worst maneuver I’ve ever seen. There is an analogous part in Crowther and Woods Adventure but that at least has the saving grace of no item that seems like a completely logical solution.

In any case, the part with climbing the rope which takes you to the second floor swaps you to “Tape 2.” (The version I was playing has the tapes merged so a tape swap is unnecessary.) The code on Tape 2 is entirely self-contained to the extent that some verbs that work on the first floor don’t work on the second floor, and vice versa.

To continue, I took the magic sword and went wandering:

Given your original inventory is all gone, and the verb set is even more limited than the first floor, the only option is to kill them all (“YOUR MAGIC SWORD ENABLES YOU TO KILL THE GHOST!”).

After slaying the ghosts, there’s another ghost, a … superghost of sorts?

KILL GHOST

THE GHOST IS IMMUNE TO YOUR ATTACK!

It won’t let you just pass by either. With only TAKE, DROP, direction commands, and KILL at your disposal, what to do?

Well, obviously, go off to another room and drop off the sword. (In another context, this might have been kind of neat, but here it is just random.)

This is followed by a “maze” of sorts with a bunch of identical ghost rooms, exploiting the fact that going in a direction just repeats the room description, beating out stiff competition for the award for Least Verisimilitude in Any Maze Ever.

Eventually, going south gets to a room with a sign.

Let’s just summarize:

- There are three exits: east, west, and south. Two of them will kill you. There is no hint as to which one.

- If you ignore the sign, by, say, wandering around the maze too fast, you will die because you have to read the sign in order to live (even if you went through the correct exit)

- If you carry the sign with you after reading it you will also die (even if you went through the correct exit).

- Dying for any of the reasons above requires a reset of the second floor. I am dearly hoping it didn’t require reloading the cassette.

Somehow I don’t feel bad about spoiling the end.

Of course, a game like this deserves a seriously impressive Amiga remake (thanks, Sean Murphy!)

Feel free to share any personal stories you have about this game in the comments. The back cover claims it is fun for the entire family. When is the last time you’ve played something that’s done that?

This game was was published by Radio Shack — the same ones who made the TRS-80 — and for obvious reasons was only available on that platform. The manual and tapes (it was originally published on two) give a copyright date of 1979, so I’m sticking with that.

It gives no author but mentions “Device Oriented Games” as the developer, who goes on to make them Bedlam (1982) and Pyramid 2000 (1982). Bedlam names the author as Robert Arnstein, who I am fairly certain was the author of every game from that company. Robert Arnstein is also credited as the author of Raäka-Tū (1981) and Xenos (1982) so we’ve got a genuine text adventure auteur on our hands. (Trivia: earlier he wrote 8080 Chess, the very first microcomputer program to participate in the ACM North American Computer Chess Championship.)

Clearly the most dramatic text adventure opening of all time.

Old Man Murray once ran a feature called “Time to Crate” which evaluated games based on how long it took for the game to have a crate. (They were everywhere at the end of the 1990s. Often it took 5 seconds or less to find a crate.) Text adventures of this era could be evaluated on the “time to reference of Crowther/Woods Adventure” system, which in this case is two moves.

Saying “plugh” tosses you inside the haunted house, with an objective to escape. There are no room descriptions, just room names (“YOU ARE AT THE DEN.”) and so far the only danger has been in ignoring a floating knife:

(Just taking the knife prevents the death.)

If you go in a direction that is invalid, the game will just print the room description again. I first thought there were mazelike loops everywhere but given this property happens in every single room it just must be a quirk of the game.

Even for the era the verb set I’ve been able to find is really sparse: directions (NSEW only), OPEN, CLOSE, DROP, GET, READ, POUR, CLIMB (which just gives a response of “NO.”) Trying to use an invalid verb on an object gives the response “WHAT SHOULD I DO WITH IT?” which is frustrating in that it almost barely pretends to understand, and the way I found to test if a verb works is to type it without an object upon which the game says “WHAT?” as opposed to “I DON’T UNDERSTAND.”

For a long time I was stuck by a locked door. It turned out to be an absolutely horrible trick. I’ll explain in a second, but take a moment to study the right side of the map and think about it first.

…

Recall the “loop” property where room descriptions just repeat if you can’t move. There’s a servant’s quarters with a cabinet next to another one with a cabinet. There is no way to distinguish the difference between looping and realizing you’ve entered a new room without having dropped something in the first room.

Things did not improve after I found the key. I came across a raging fire. I happened to be holding a bucket of water (one that magically refills if I pour it, even) but I am completely unable to apply it to the fire.

It’s been a while since I’ve skipped finishing a game for this project without completing it, but I just might have to invoke that option.

This is the first “full length” game for Eamon past the Beginner’s Cave, and is written by Donald Brown himself.

“Girlfriend” as a choice was automatic. If your character is female it assumes “boyfriend”.

In order to play I had to take a character through the Cave first to gather enough experience in combat, then port that same character into the Lair. I can’t emphasize enough how pleasing this sort of continuity feels; I’m fairly sure this is part of the reason Eamon took off.

There’s sort of a plot?

This doesn’t play nearly as fun as Beginner’s Cave. That game was tight enough that it felt like a genuine dungeon crawl and all the features had a chance to shine. This game has the same problem as Greg Hassett where more space for rooms leads to more rooms that do nothing.

(Click on the map for a larger version.)

Mind you, the RPG system is still relatively strong, and I had emergent sequences like this one:

- I ran across a “black knight” whose heavy armor was very hard to penetrate in battle; fortunately, the knight fumbled and dropped their sword which I was able to grab. It then proceeded to run away. This led to a weird inversion where I was chasing a black knight trying to hit it (for the weapon experience, of course) like I was the relentless stalker of some horror movie. Eventually I got tired of trying to knock the knight’s hit points down to zero and let it live.

- In the process of knight-stalking I came across a “wandering minstrel eye” who was friendly and started following me around. Not helping in combat, mind you, just following, like a small puppy.

- I met an (evil?) priest in a room full of ancient books which I bested in an extended combat. Unfortunately, in the midst of battle the priest decided the wandering eye was a valid target and slew it in a single blow.

- I found the girlfriend in need of rescue tied to an altar with another evil priest. Unfortunately I was low on health and died before I could free her.

Related to health, I had enough money to come in with a spell this time (HEAL) which predictably healed some damage from prior combats, but as far as I could tell only worked once during the game. It’s almost more like I bought a consumable potion rather than a spell. Maybe it regenerates after enough turns or some such but I wasn’t able to figure out a way to use the spell again.

After the debacle above I made a second character which I first ran through the Beginner’s Cave again trying to get better statistics. That character fumbled and killed himself with his own sword before he could even make it out of that game. Whoops.

I repeated the sequence with a third character and much more successful character before bringing to the Lair. This time I was a bit more selective in my combats and managed to free the girlfriend, who then was able to contribute to combat. I then made my way through the maze (see map above; the “loops” connecting bottom to top were non-obvious) and defeated the minotaur mainly by hanging alive long enough for him to drop his weapon.

The strongest aspect of the game past the regular Eamon system is the amount of optional activity. Since no treasures are “required” and simply result in more gold at the end of the adventure, monsters and puzzles can be ignored to an extent there’s a “branching plot” feel.

For example: There’s a stone with the word “CIGAM” on in and if you SAY the right word (I’ll let you guess which) an emerald will pop out. There’s a portion that appears to be recently dug and if you bring a shovel you will find some gold coins. There’s a room with 5000 silver coins which are tractable to carry if you find a magic bag in another part of the map.

There’s also two “neutral” monsters: a blacksmith with a golden anvil (who is neutral upon you entering his room, but you can kill and rob because D&D) and a gypsy with a wicked looking sword. The charisma stat also comes into play here. I suspect it’s possible to make friends with the black knight with a lucky enough reaction, for instance.

There’s even one “backup item” branch. At the beginning there’s a coffin with a skeleton; if you kill the skeleton you get a “skeleton key” you need to unlock a gate later. If you skip fighting the skeleton (not unusual to occur, there’s a river after which is a one-way trip), the previously-mentioned priest with the ancient books has a skeleton key you can use instead.

While this game and the next couple Eamons are early enough in history I wouldn’t want to miss them, I do suspect enough of them tip far enough into the “RPG” category I may start skipping them in my All the Adventures list. As is, though, Eamon won’t be coming back until I’m out of 1979.

Retro enthusiasts who follow this blog may be wondering why the only home computer featured so far is the TRS-80. I apologize; I did try with Lords of Karma to use a Commodore PET or Apple II version but neither was cooperating. Now, finally, we have our first game designed specifically for Apple II.

I prefer the title screen in monochrome to the color version.

Donald Brown’s achievement with Eamon really is remarkable. He created essentially an “RPG campaign system” which lets you make a character that can then play in multiple adventures. I’ve occasionally heard talk in the interactive fiction community of a “shared universe of objects” that allows porting things between games, but it never really materialized; here it was done in 1979. (Definitely 1979 even though it’s been reported differently elsewhere; Jimmy Maher has a blog post about the issue.)

Failing at character creation can be deadly.

The game starts with you specifying a name (which corresponds to a saved character), choosing male or female, and then being handed a randomly-chosen set of statistics.

Character creation can be deadly even when you do follow directions.

This is followed by a long set of instructions, which I’ll summarize: There are five weapons classes (clubs/mace, spear, axe, sword, bow) which I’ve just listed in order from easiest to use to hardest, although I gather swords cause more damage than maces and so forth. Armor (leather, chain, plate) makes it harder to be hit but also makes it harder to hit others, and shields are usable when not wielding a two-handed weapon.

You can carry weight up to 10 times your hardiness; your hardiness also serves as your “hit points” although the amount of damage felt is conveyed in text (“YOU DON’T FEEL VERY WELL”) as opposed to numbers. Agility affects your ability to hit monsters. Charisma affects the prices in shops and the friendliness of monsters (more on the latter point later).

There are some magic spells, although as far as I can tell stats don’t affect their use (other than them having effects *to* stats).

I mentioned a “shared universe of objects”; as noted in the screenshot above, it isn’t complete (one author can’t create a magical object which then affects other games) the persistence of money, weapons, and armor is non-trivial and makes the general experience of Eamon feel more like a modular set of stories rather than many distinct ones. (I should add many later Eamon games do end up customizing enough to be stand-alone; there was even an Eamon game in IFComp 2010.)

In any case, after choosing to embark an adventure the player is prompted to swap disks; without swapping disks, they are sent to the “Beginner’s Cave”. The game is emphatic about the “beginner” moniker — if your character is too experienced they won’t be allowed in.

The map is fairly straightforward but does have the feel of a room-by-room Dungeons & Dragons crawl.

The “charisma” statistic plays a big part in what happens. There is a “hermit” and a warrior named Heinrich, both which can be peaceful and follow you around. (There’s random chance going on here, so even with a higher charisma stat it is possible one or the other may not be friendly.) They will then fight with you in combats with monsters, which helps enormously with the chance of survival.

There’s a chest which is really a mimic, a bunch of rats, and a pirate with a sword with a magical flame (that will activate for you with the word TROLLSFIRE). The combat system does make the world does seem a bit dynamic; enemies can run away from you multiple times, causing monsters in one room to end up in another. One time I chased the rats into the room with the hermit. I hadn’t befriended the hermit yet but fortunately he turned out to be on my side and started killing the rats.

“Critical hits” and “critical misses” are in; you can fumble and drop a weapon in the middle of a fight, or kill an enemy instantly with a single blow. (The downside is the same can happen to you; once the pirate killed me in a single blow when I had full health.)

There are magic items, but fortune and death are dealt in equal numbers: There’s a bottle, which when drunk, will heal wounds. There’s a book, which when read, will automatically kill you.

The ostensible “goal” is to gather as much gold and items as possible and then leave once satisfied. However, there’s a secret door (which is revealed by hanging out in a room and LOOKing, just like Lords of Karma) which leads to a priest and a stereotype.

Once the battle against the priest is won, Cynthia will follow you around; rather notably for a videogame escort mission, if getting into combat she will run away to safety rather than get herself killed.

Since the game is essentially goalless, you can leave whenever you like:

Even though Eamon games seems to classify more as “RPG” than “Adventure”, it feels like their popularity at the time is not proportional to historical memory. There are at least 255 Eamon games. Donald Brown clearly provoked some sort of affection for his creation which lasted a long time.

This cover is from a dodgy plagiarized version with the author name stripped out. You can read more details at The Eamon Adventurer’s Guild.