From The Retro Cavern.

(Continued directly from my previous post.)

In the past I’ve tried my best to point out how the various text games I’ve played (despite a very common set of elements) nevertheless have strong fingerprints which distinguish them. This game is no different, and I want to do some compare-and-contrast with two sections. This is useful from both a history-of-games standpoint and a theory-of-games standpoint.

Picking up the action from the obligatory troll’s toll bridge, I tried paying the troll and exploring a bit farther.

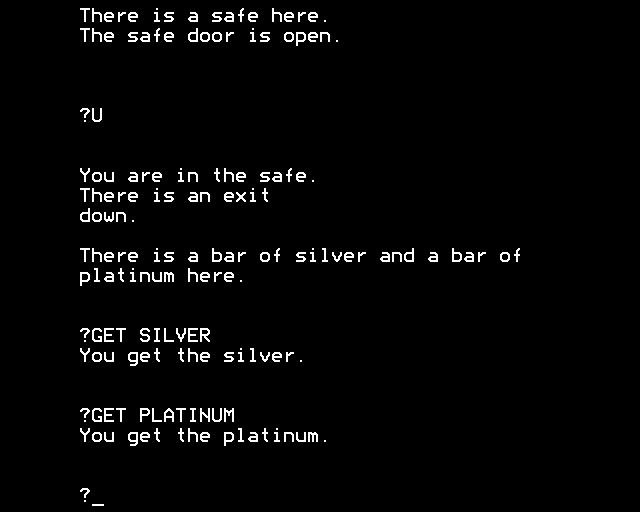

I was given the word “diaxos” in one of the rooms (it gets whispered like “Y2” does in Crowther/Woods). The word “diaxos” give a “very loud creaking sound” no matter where it is used, and the trick is to realize that this is the sound of the safe (back on the other side of the troll bridge, by the library) being opened.

By default there’s a bar of platinum but if you hand something over to the troll beforehand, it also ends up in the safe. So that problem’s resolved: you give up a treasure and you just get it back later.

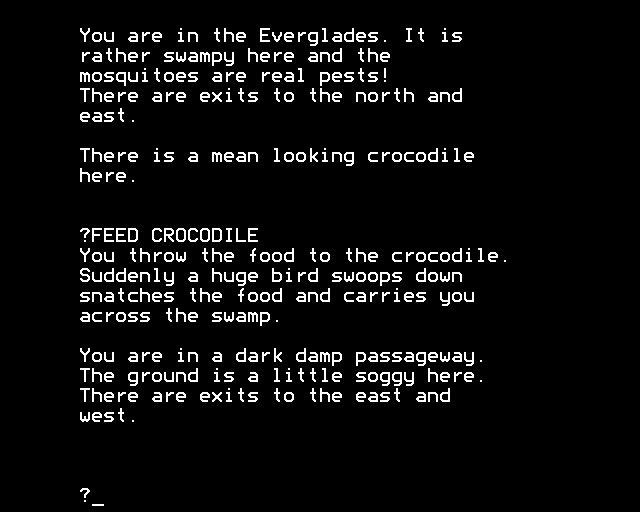

I also had encounters with an ogre, orc, and dragon in that order, but I want to save that for what will hopefully be a final or close to final post, and focus on the Everglades area. I was getting chomped by a crocodile who just needed some food (although the exact sequence of what happens is a bit unexpected).

The upshot of the sequence above is that the trip here is one-time-only. You can safely go back in the Everglades, but the still-hungry crocodile will still chomp you if you try to go by again. Fortunately, there’s no real need for a second trip, because the whole area has no puzzles: just locations with treasures lying around.

Treasure rooms marked with color.

In a sense, this means the game reverts to the type from some early games like Explore or Chaffee’s Quest: just movement and treasures. (Probably. There is one possible secret.) Furthermore, it has the random-placement style of those games; there’s a “yellow brick road” in one spot, some quicksand in another, a treasury, and a fairy grotto.

However, despite just being rooms, there’s some semblance of environmental narrative going on. The quicksand has a plank left by a previous adventurer.

Also, you can safely go “down”, but just end up at a dead-end: “Oh dear you seem to have struggled through that quicksand for nothing”.

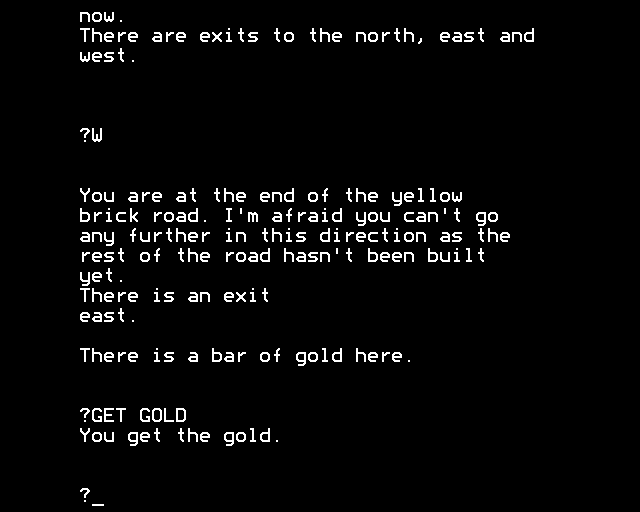

Similarly, the yellow brick road was only previously yellow:

And it is possible to make it to the end of the line where the road stopped being built:

The effect is really light and vignette-based. I did mention one possible secret; the fairy grotto has no treasure and it is highly tempting to think a magic word or something like that goes here. On my “best progress save” I am saving nabbing all the treasures in this area because of the fairy grotto, although it could easily be more environmental storytelling.

One other subtlety I want to point out — and this is true of every area, not just this self-contained one — is how the structure of the text is part of the user interface. If we go back to original Adventure (the only reference for this game) there is one major standard established right away:

YOU ARE INSIDE A BUILDING, A WELL HOUSE FOR A LARGE SPRING.

THERE ARE SOME KEYS ON THE GROUND HERE.

THERE IS A SHINY BRASS LAMP NEARBY.

THERE IS FOOD HERE.

THERE IS A BOTTLE OF WATER HERE.

Namely, that objects that you can pick up are separated from the main text. There is, of course, an easy technical reason for this (it is a lot harder to modify the body text than it is to concatenate a bunch of object-in-room messages) but it also serves to make the player have an easier time. By contrast, consider the ICL game Quest:

You are in a small log cabin in the mountains. There is a door to the north and a trapdoor in the floor. Looking upwards into the cobwebbed gloom, you perceive an air-conditioning duct. Lying in one corner there is a short black rod with a gold star on one end. Hanging crookedly above the fireplace is a picture of Whistler’s mother, with the following inscription underneath: ‘If death strikes and all is lost – I shall put you straight’.

The short black rod which you can pick up is placed in the middle of the text, and furthermore doesn’t have the line-skip to separate it. Despite both cases dealing just with prose, the first example more easily highlights the things a player can interact with, and so the text structure itself provides a UI.

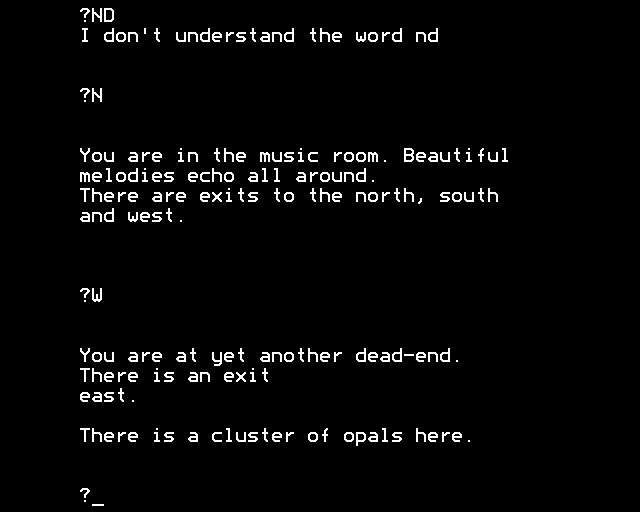

Now consider Sphinx Adventure:

The format is

You are in a music room. [Statement of room name] Beautiful melodies echo all around. [Description of environment]

[Break to next line]

There are exits to the north, south, and west. [Listed description of exits.]

Notice how this easily gets across: the room as a short name (for ease of mapping), and the break between description and interactable parts (in this case the exits). When an object is included there is a further break.

You are at yet another dead end. [Room name, no description.]

[Break to next line]

There is another exit east. [Listed description of exits]

[Break to next line]

[Another line break, meaning the break here is different than the break between room name and exits.]

There is a cluster of opals here.

This conveys quite quickly the one direction you can go and what you can take, and the two kinds of breaks subtlety adds another bit of help in reading what the player needs.

This seems like a small and obvious thing (and it was at least started off in Adventure) but certainly not everyone followed the system so cleanly. (Having windows like the French Colditz game I played recently is another approach, but one with different issues.) One major gameplay consideration is if there’s any important objects sequestered in the “room description” portion. This game the answer seems to be no; you can’t refer to the plank at the quicksand, for example. Many a time I’ve been stuck has been when a game seems to establish this “sequestered room description” setup but then violates it. The biggest thing to remember in UI design is consistency, lest your UI gets mocked like like this chart of all the different ways to go left and right in Starfield. (I especially like how in one case it’s the letters Q and E and in another the letters Q and T and yet another the letters Z and C … why?)

Arguably, whether the convention of separating the carriable or interacting objects from the text is orthodox is debatable. It does somewhat break the immersive qualities of the game, which I find to be a defensible argument to not doing it, because immersion is essential to the IF genre. On the other hand, it makes things more accessible to the player, but not all games are aimed at beginners. Orthodoxy is not a good thing for a discipline that depends on a creative effort. Mixing decoration with significance in descriptions may make things harder, but that is how scenes would be presented in the adventurer’s mind by the implicit narrator.

If the mimesis argument is not convincing enough, let’s just say that the IF genre has in later eras been defined by the degree of experimentation and “abuse of the tacit rules of construction” by authors. Very illustrious exponents of the IF elite have had unreliable narrators, unreliable puppets, rashōmons, blurry distinctions between scenery and objects, deliberate linguistic traps, and many other creative deviations of “the norm”. And we are all the richer for it; but these excursions may not be for everyone.

Give me Sphinx Adventure over all the self-conscious smartarsery that masquerade as text adventures nowadays. Ever wanted to play a Twine based one room game in which you can have 73 different conversations with a tin of creosote? No me neither. Mulldoon Legacy and its parent Curses showed me how the genre should develop. You can keep 99 percent of the modern stuff.

I assume that was a joke, but… is there a Twine game where you talk to a tin of creosote?

Now I want to make one! Just for the experience. (although it seems like it’d be better as parser, so you could LICK TIN, KICK TIN, ARGUE WITH TIN, etc)

the closest to the experience right now would be Pick Up the Phone Booth and Aisle

https://ifdb.org/viewgame?id=6vej1yd9quwfm9qn

>frotz me

You now glow brightly with an unnatural light. While you’ll never be in danger of being eaten by a Grue again, you’ll also be incredibly unpopular at the movie theater.

btw, was meaning to ask, did you finish Prom Dress?

Roger, Is that a reference to any specific games that I don’t know about? I’m just curious because it sounds oddly specific. The tin part has me for a loop, but otherwise it might not be too far off from a critic of Galatea…

This reminds me of several examples of IF that appear in the “Road to Gehenna” DLC of “The Talos Principle” (a first-person-puzzle game, not IF in itself). Without giving anything away, they are small text adventures created by rogue AIs trapped in a virtual prison and trying very hard to imitate the examples of human art they had seen. They are taken absolutely seriously as deep, philosophical meditations on life but the joke is they are nonsensical, pompous drivel — this is evident to the player but not to the in-game NPCs. I think the authors (Croteam, well known for “shoot all that moves” games) were trying to make a statement. :)

Sturgeon’s Law applies to old games as well as new, though.

The point and click adventure The Sea Will Claim Everything is by the same author, if you don’t mind point and click.

(WordPress won’t let me reply another level down…) @Jason I have played Pick up the Phone Booth and Aisle, or maybe it would be more accurate to say “tried to play”, lol. I remember it being very obtuse, but then it is basically a gag game (just like Pick Up the Phone Booth and Die).

I wasn’t really meaning to condense my outlook to any particular game. I have tried several “modern” games but they leave me unmoved.

I don’t think in reality that there is a game where you converse with a tin of creosote. Although I am sure we can all think of similar games; some are parody but most aren’t.

Prom Dress remains on my to-do list. A bit like finding Picnic At Hanging Rock from 1975 I occasionally stumble into something magical even now. Without hope what is there?

It was suggested somewhat tongue in cheek, but you have to convince the tin to allow you to open it by vanquishing its personal depression and withdrawal from the world of wood preservatives; was it caused by the rising tide of bitumen and shellac users so that the tin has lost its sense of worth? Maybe some Johnny come lately protective sealant has been invented that has become the new poster boy of the timber protection world. It all plays out in front of a plain wooden shed that has no door. If you finally manage to get the lid off, the shed collapses on top of you in a sudden gale and you are crushed to death.

Pick Up The Coal Tar And Die? Nothing is preserved, neither shed nor your own life.