One of the key skills in game design is being able to understand things from the mind of another person. They don’t know what you know; you have to imagine you are seeing information as they are. Beginners to designing puzzles especially will often include leaps that are clearly out of mental bounds of their players. The technical term (well, one technical term) is “cognitive empathy”.

I think the problem with The Scepter is the young author lacked a.) a sense of when puzzles are easy or difficult and relatedly, b.) cognitive empathy.

(Not weird for a first time author! And we’ll come back to Simon, so we’ll get to see if he’s made progress.)

From the Museum of Computer Adventure Games.

Here’s the item stash from last time:

wheel, crystal ball, sword, goblet, lamp, acorn, wire, diamond, axe, bag of dirt, old boot, key

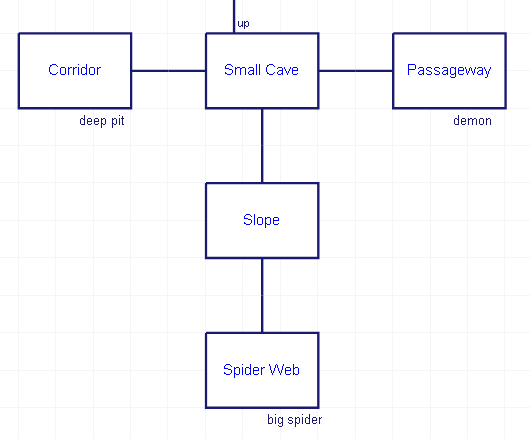

Here’s the map from last time:

One of the puzzles causing issue was a giant web with a spider. Any direct attack on the spider was ignored; the spider equally ignored the player in their efforts to kick, push, tickle, etc. in the hope of something, anything to happen.

I need to check with hints via rmartins; the puzzle is entirely unsolvable from the room itself, but rather you are supposed to look at the room adjacent, the Slope. From there, you can ROLL the WHEEL which will head downhill and smash the web.

This of course assumes the player knows the slope goes down, that the wheel is big and stable enough to roll free-standing on its own, that the web is placed such that it would make sense to get taken down by a wheel, and that the web is small enough for the same. Failure on any of these can lead to a very difficult-to-visualize puzzle; in particular I was thinking the web as being too large for such a thing.

Many of these could be fixed by a more responsive parser, so technical issues are partly to blame. It’s a pity because this is quite a clever puzzle in a way: a very indirect and creative approach to the solution. I’d probably (taking my game-designer red pencil) also allow DROP rather than ROLL as a solution; even though it is possible you might have the wheel roll down by accident that way, it is an unlikely dumping spot for the player. As an extra bonus you could have other items slide down the slope to emphasize the physicality of the space and give a hint as to what’s going on.

Past the web is a locked chest. If you have the WIRE in inventory you can PICK LOCK (note how LOCK is not even a described noun in the game, you just have to infer the command will work).

This gets a *SKULL* which is one of the three parts of the Scepter that we’re seeking.

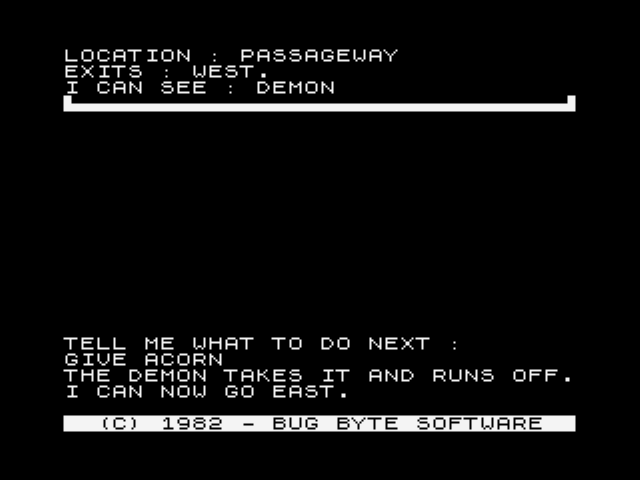

Moving on next is the demon. (Again, I needed an rmartins hint.) You’re supposed to give it …

… the acorn. Sure? Maybe it’s a demon-squirrel. LOOK doesn’t give any info so you just have to hit this randomly.

Past that is a *STAFF*, so that’s two parts out of three.

Over to the pit, you need to take the crystal ball — which already worked to gazing and seeing a goblet and a furnace — and rubbing it.

This again seems like a failure of cognitive empathy. Imagine the process from the player’s end: how will they solve it? The only real way seems to be testing RUB at random to see if it is magical, and then testing RUB in every location looking for an effect. I could see in the author’s mind thinking that — oh, the only way across is magic — and thinking there wasn’t a big leap in logic, but it isn’t even obvious that crossing the pit is desired (I tried for a while to survive the jump in, or use a rope from the demon’s direction as a way of climbing down).

The ghost puzzle is terrible but let’s zip by a moment for the easy puzzles. There’s that furnace where you can melt the goblet, getting a coin (not only was there a vision of the two together but the goblet said MELT ME, why so many hints on this and not the acorn-loving demon?)…

…next to a vending machine to use the coin.

The scroll allows teleportation back across the pit.

Then there’s a “fierce dog”, where the only tricky aspect is you’ve been trained by the spider and demon to look for a “weird” solution. No, you’re just supposed to kill it. With your sword.

A sad dragon is made happy again. I mean, I got it first try at least.

And then we reach a puzzle that would truly bit nifty if it weren’t for a verb issue.

Remember the bag of dirt I was making fun of from the start of the game? I realized quite quickly this was meant to be the Indiana Jones weight-swap. You have to SWAP, SWITCH doesn’t work, nor does PUT DIRT or many other variants.

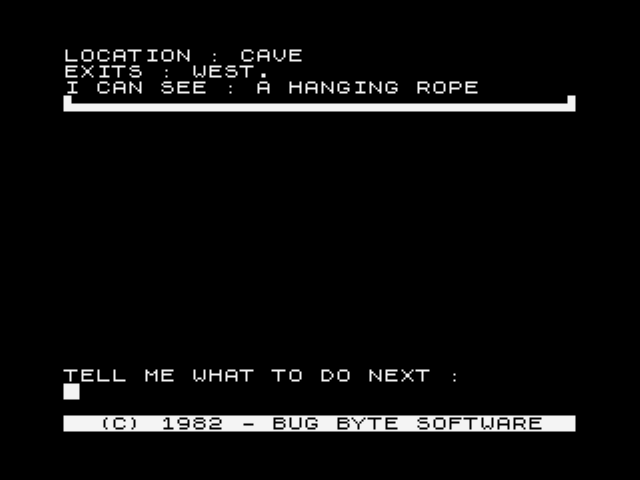

Before leaving you need to deal with the ghost, and boy, you thought the acorn was unprompted:

This isn’t “moon logic” — SAY HELLO isn’t a 100% absurd thing to do, after the fact — but it has zero prompting and is it highly unlikely someone would just hit upon the act naturally. Even if someone gets close (“I want to talk to the ghost”) other words like HI don’t work. It has to be that exact command.

Using this advice, you can go back aboveground, BUILD SCEPTER to put together the staff, ruby, and skull, and then WAVE SCEPTER while at the chopped-down tree in order to teleport home. Why we could not walk back the way we came is undisclosed.

I think you are being too empathic with the author. I think that, if it had been published later the sheer “competition” with other authors (i.e., simply more software available), would have made this game unpublished. The descriptions are simply missing, I thorough debug/testing is completely needed, and the parser is lacking (though I’ve been browsing the listing and it seems to include some machine code). Although the memory limitations of the ZX81 can explain some of it defects, I think the game is clearly sub-par.

I thought I was being pretty obvious the game is bad. I realize my writing style is “always try to look for the good in things” but really it is more of a case of I’m more interested “why did things happen the way they did”. I’m trying to create a “history of game design” essentially.

In this case since there’s later games (and I’m going to date the unpublished sequel to this in 1982, so it won’t be that far away) I’m wanting to remember points to check later to see if the author improved.

Man, your idea of building a reusable verbs list and revisit it across games is just wonderful. That was at the core of making it possible for me to solve most of this game. It really makes a lot of difference and makes these old school treasure hunts *much* more enjoyable!

That said, the SWAP was weird; first SWAP RUBY then FOR DIRT. It took me a few minutes to realize I had to pull a Colossal Cave Dragon kind of trick and not use a verb for the first word. I see that you didn’t comment on it, did you think it was clear?

Some other couple of things that I’d comment on:

* The slope puzzle made sense “locally” so-to-speak, i.e. there is a slope, roll something down it, done. But I agree that, by itself, that’d not be enough; what helped me was that I looked at the verb list and tried to roll all items elsewhere, and the wheel had a custom response, so I knew I’d end up rolling it somewhere. In a way, a more responsive parser would have given you a more “global” sense of logic (as in, the puzzle makes sense as a whole, as a thing in itself), but on the other hand, if the parser was powerful enough that many combinations of verb+items would give custom, but ultimately useless, responses, just for the sake of aesthetics, then I might not actually have realized that rolling the wheel was an important thing. So to be honest I’m a bit on the fence on whether the broad reach of modern parsers actually help you with the actual puzzle-solving of such games.

* Rubbing the crystal ball anywhere also gives a somewhat-custom response, “I can’t do that… yet.” So that would be a clue that you will end up rubbing it somewhere for something special. I am not saying it’s good design, but I have to be honest and say that sometimes I miss this kind of constrained approach to game design, where it’s easier to determine the actual objective game boundaries. A modern parser-based puzzle adventure will give you so many things to consider and think about, and so many abstract and wild possibilities, that I’m not sure I can handle the kind of cognitive overload that this generates. Of course, there are many ways for “modern” games to include this kind of in-game-clues when a certain verb+item combination is important, but many don’t do that, and the powerful Inform parser by itself cannot save a poorly-designed game.

The only game that really foiled me on verb-testing was Time Zone, where some disks had unique verbs not on other disks.

That’s pretty good logic! I sometimes have used odd parser message reactions (right action, wrong place) as a help but I just had trouble sorting things together here.

When you look back at the many games you’ve played I think it becomes easier to confidently avow what is a fair puzzle and what isn’t. For instance, the “London Dry” puzzle in Acheton would I think be universally accepted as hard but fair. Written in the pre search engine days, it would have sent most people (even English I think and that is a very English item) scurrying to their nearest encyclopaedia to do some research. As the puzzle was created by a man whose entire professional history was predicated on book research he would have considered it as natural as breathing. Other puzzles in the same game (the ningy for instance) may be patently unfair.

From the same stable the famous item in Quondam that is described completely differently depending on which direction you approach it from (even after being picked up!) is absurdly unfair and of course game breaking through no fault of the player. The catch-all phrase “Welcome to the land of Quondam where all things magical are possible” is a lazy get out to excuse some ridiculously unfair puzzles. I wouldn’t consider the two puzzles solvable by using obscure verbs in the same game unfair. On the other hand, games where you have to guess passwords without any kind of previous clue are totally unfair. I can think of at least three where “open sesame” or “abracadabra” work as puzzle solutions for no apparent reason other than a quick get out clause for the author.

Learning by death was of course perfectly acceptable once upon a time and I have no problem with those games as they can be very funny and it takes but a few seconds to reload and try another tack. What I like to term “microwave games” i.e. modern ones where you have to publish a walkthrough upon release, have no hard or soft locks, no nasty deaths to send the lachrymose player sobbing to his psychiatrist and tick every politically correct box are anathema to me and just as annoying as The Sceptre (sic).

I suspect I am in the minority here. Even in the worst games as you said above there is normally something to enjoy. I am interested if you have ever played a game you really hated and derived nothing whatsoever from. I would guess probably not.

African Escape was pretty bad but kind of interesting from an outside perspective

the one I thought was just hateful was Adventure in Ancient Jerusalem.

Hah, I love your concept of “microwave games” and agree 100% that they are aggressively uninteresting. I think there was a time when the goal of an adventure game was to challenge the player; I usually say that the game has not started yet until you get stuck for the first time (and if you never get stuck, well… then the game ended without starting). Of course, good puzzle design then comes from being able to make puzzles where you can get stuck and unstuck on a healthy, reasonable basis, with some nice “aha!” moments. That is of course extremely hard (and as far as I know, entirely ad hoc). Maybe this kind of challenge is a relic of the past, when one might buy a new game every few months, and the world moved a bit slower.

On the other hand, nowadays it seems that if you get stuck on a game that is seen as a design flaw? Many other goals have emerged over the decades when designing a so-called IF game: telling a story, political/ideological commentary, experimentation with the medium, etc. Getting stuck on a puzzle will hinder those other goals (whether any of these other goals can actually be reached effectively with an IF/text-adventure game is of course a topic for another discussion).

The way I see it, there is a quasi-academic community of IF players/designers who are basically 99% of the audience to each other’s games, and with the staggering number of games being constantly released (especially in the many yearly competitions), getting stuck keeps you from moving through your queue. I’m an academic myself and I see a lot of similarities between my own research community and the IF community (in terms of how the designers/writers are also the players/readers and as such the content is directly shaped by what we expect the other colleagues to say/think about our work).

It’s also worth pointing out that if you want to win one of those contests you’re probably not going to be making something very hard or requiring a lot of restarts. In Ifcomp you only get a hour for each game, though others allow for more time. Deaths shouldn’t be a problem owing to most modern interpreters having an undo function, but dead ends tend to be looked on very poorly. People wouldn’t even recognize it unless it was very obvious or the game outright says it’s going to do it.

Interesting; there’s not a lot of love lost out there. I support one particular side of that eternal conflict but this isn’t the place for a political debate. And remember when you feel the awkwardnes of reviewing a game that Stiffy Makane is still years away.

yeah, the bad design doesn’t have to do with the stereotyping (and we’ve honestly seen worse, it’s just an extra bit of kicker) — the softlock at the start just by going in the wrong direction, the bugs, the completely unmotivated magic word bit where you have to abuse the HELP command, the section you need to map out with multiple deaths (and there’s no save game feature), the hidden “treasures here” message — it was just a painful slog all around

we’ve got a 1982 sort-of equivalent to stiffy makane (actually there’s a 1981 game too I haven’t played yet and isn’t indexed anywhere, but I’m unclear how makane-like it is)

It’s up against some stiff opposition.

A propos of nothing I drew up a list of what I consider to be the fifteen most difficult text adventures I have ever played (roughly in order). This means difficult by design rather than difficult by bad programming.

Quondam

Philosopher’s Quest (Brand X)

Acheton

Ferret

Xeno

SNOAE

Hezarin

Castle Blackheart

Warp

Castle Ralf

Cornucopia

Reefer Island

Mulldoon Legacy

Stugan

Savage Island Part II

what’s SNOAE? it’s not even up at CASA

Cornucopia is not bugged like Catacombs, right?

you might like Finding Martin, that’s a more recent game that’s definitely on the tough side

https://ifdb.org/viewgame?id=tmf83w8qcbeiibeq

I’m curious, would you consider Personal Nightmare by Horrorsoft to be a text adventure? Granted, having played PN and not any of the games you mention I suspect it’s a lot easier, but it seems to be something of a standard for graphic adventures with insane difficulty. (it has a parser, so it’s some weird hybrid)

I must admit I have never really played many split graphics / text adventures as I am a self confessed old fogey traditionalist who prefers pure text. I am sure I have missed out on some good games though because of my stance.

I had a quick look at some images from Personal Nightmare and it looks like a proper adventure game. Certainly the reviews suggest it is very difficult.

Finding Martin would definitely be in my top twenty toughies. What an enormous game. I reckon the coding for the watch must be larger than most games in their entirety.

Cornucopia is mercifully now a fixed game; the latest version is available on CASA. It is a real stinker, much larger than Catacombs but at least solvable. There is a lot of spell casting but it is another game that has almost endless soft locks and some unfair puzzles.

Whoops I meant SNOSAE. This game must have more puzzles than almost any other. It is extremely difficult and probably a p*ss take.

Castle Ralf is an old DOS game that has the longest, most elaborate puzzle I have ever come across. I still haven’t solved it. It includes a sequence which appears to be formatting your C: drive.

oh, SNOSAE the ifcomp entry! That was back when people were supposed to be more serious about the two hour limit (I think because of games like that it has relaxed a bit and a long game is ok, just the judge should put their score after two hours) but for 1999 it was incredibly cheeky

Is there an IF competiton that encourages old style parser-based epic works nowadays? I get the impression that a lot of competitions have been aimed at forcing people to write smaller games and bundling a solution in as well. I may be wrong of course.

ParserComp tends to be more oriented to the old school (not always “epic” but that’d be hard to have people cranking out epic games yearly!)

https://itch.io/jam/parsercomp-2023

You may recognize the person who won this year

there’s some oddities but they’re more in the “freestyle” category

There’s usually always a few in classic IFComp that qualify, I’m guessing you played the Only Possible Prom Dress game from last year? That’s long and old school

https://ifdb.org/viewgame?id=u4u57v2ggfcqvll7

I downloaded The Only Possible Prom Dress recently and have had only had time to take a cursory glance but it looks right up my street. I played Not Just An Ordinary Ballerina a few years ago and I was very impressed by the all-round strengths of the game. I suppose coming from a seasoned Science Fiction author like Jim Aikin the quality of writing should come as no surprise but the puzzle elements were of a high standard too. He sent me an inchoate map and some notes of the sequel a few years back when he was still mulling over whether to turn it into a full-blown offering or not. I remember an octopus but I’m not sure how much of what he sent me back in 2018 actually ended up in the finished game.

Actually for Castle Blackheart read Castle Blackstar. Very Zork like but considerably tougher.

BEYOND MOON AND BANANA LOGIC!!!