We’ve encountered Ken Rose once before, with the 1981 game Palace in Thunderland, co-authored with Dale Johnson. That game was legitimately excellent (in the confines of being a difficult puzzle-box adventure). It is unclear how the workload in that game was allocated but clearly by 1982 Rose had some adventure experience.

Softline Magazine, also known as “the Apple II magazine Ken Williams started up to help publicize On-Line Systems”, started running a column titled Adventures in Adventuring in its January/February 1982 issue by Ken Rose, intended to teach how to program adventure games. Unlike some other “teaching” material we’ve seen (where it is possible the game came out more simplistic than intended so the author may have tacked on “it’s for learning” as an excuse) this column genuinely tried to be thorough, with clear explanations in the column and extensive REM comment statements in the code itself.

The first three issues from 1982.

For now I intend to cover January, March, and May. The January game isn’t even an adventure, the March game is clearly a demo, so the title for May (Journey to the Planet Pincus) is the only one I’m using atop this post. The remaining three articles for 1982 I’ll tackle some other time.

Neither the source for January nor March is available in any form other than print, so I had to type the code myself (or rather, copy the mangled Optical Character Recognition file and then do a bunch of editing for cases where the algorithm couldn’t distinguish a zero from the letter O or kept turning dollar signs into vertical lines).

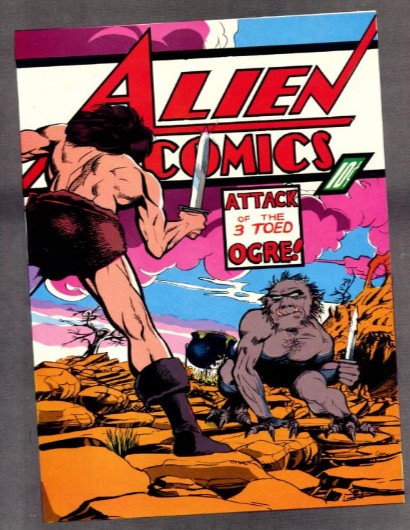

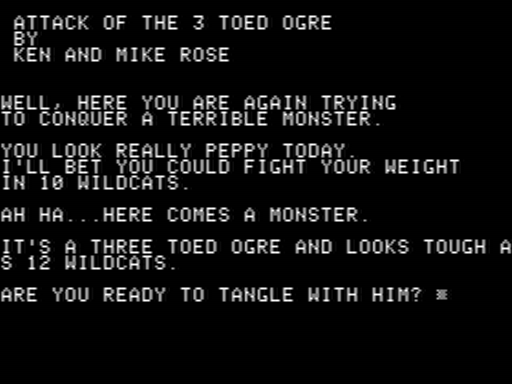

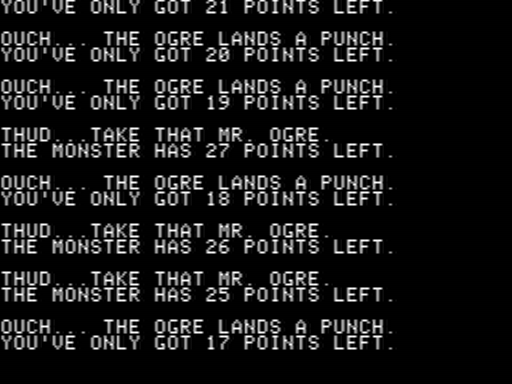

The first game is simply a combat against a monster with essentially no choices. There are a set of prefatory screens which explain how dire your situation is fighting the titual three-toed ogre.

Mike Rose (some relation, I presume) is a co-writer for this game. He’s listed as the sole writer on the game Pincus but I’m listing the pair as co-authors due to the article’s integration.

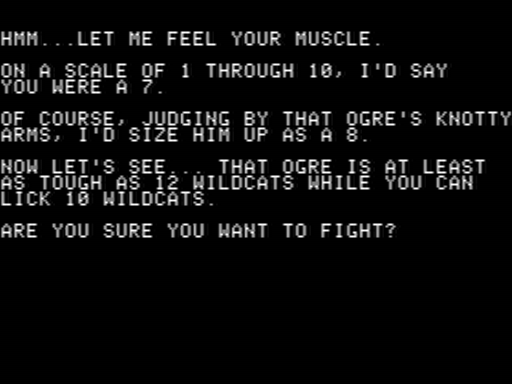

Nimbleness and intelligence are also sized up. Later questions switch from needing to say Yes to needing to say No (ARE YOU SURE YOU WANT TO FIGHT? vs. DO YOU WANT TO QUIT?) but once the fight is started it runs on its own, with a small pause while waiting for message to appear.

The odds seem generally titled to the ogre (or at least when I tried multiple times I lost more than I won) although the game does try to fudge that stats to be comparable:

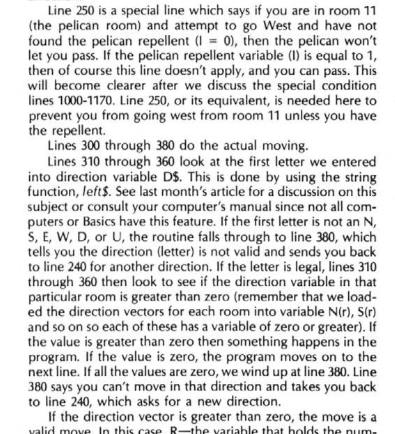

The villain, too, must have values set for him for each of the four attributes. Line 305 reveals an LF [limiting factor] of “CO,” with CO representing the constitution rating for ourselves. To prevent the ogre from being either too strong or too weak to be our worthy adversary, we have ins true red the program to make the number of sides on the die equal to our constitution value. In other words, if our constitution is rated 8, the ogre rolls an eight-sided die to determine his constitution value.

The code is sufficiently annotated for the interest of someone coding in 1982. There’s isn’t much interest to the current player.

The March article is specifically about parsing.

There is some extolling of the virtues of Zork and most particularly the fact it understands complete sentences with conjunctions and so forth; but rather than speculating how that actually works (it is possible the author doesn’t know) the source code for the column goes into a demo for a simple two world parser. There is a section header marked What Happened to the Frog? which may be the title for the game, or it may be the game just doesn’t have a title.

Now, Ogre’s source code wasn’t too tough to handle, but in this case, getting the screen above was a journey, because the printed code has mistakes. I in fact needed to guess what was the author’s intent and interpolate, bringing out the true 1982 experience (type-ins had mistakes all the time).

ASIDE: For this game there’s no name listed so it is unclear if this was Mike Rose, Ken Rose, or a combination of both who wrote the code; either way, any mangling could easily have happened on the magazine editor’s end.

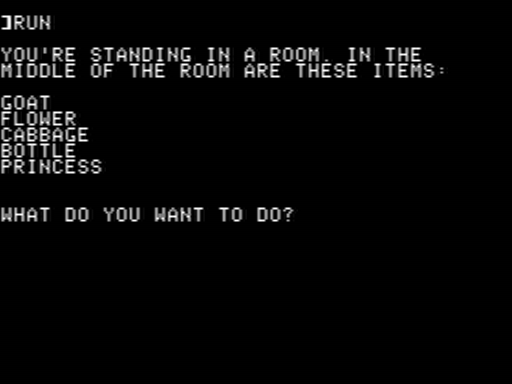

Look how the code kicks off:

What this is doing is reading verbs and nouns from DATA lines later in the source code. It loops four times (A = 1 TO 4) to read four verbs as V1$(1) through V1$(4). Then it loops five times (A = 1 TO 5) to read five nouns as N1$(1) through N1$(5).

This would be straightforward except the source code doesn’t provide five nouns. It only provides four.

This means the game throws up an error right away when the code is typed exactly as written. Notice how line 955 almost has a noticeable gap, like someone covered a noun with white-out.

I tried first simply only reading four nouns (assuming one had gotten removed in editing without the fix prior) but the game was still doing wacky things as if there was some kind of noun mismatch. I eventually settled on realizing the gap must have had a CABBAGE, so put the noun back in, although a few lines still required fixing. With my version of the source code whenever I changed a line I added a REM 2023 after it. It is unclear what is an “authentic typo” and what is simply a printing error, but given the game doesn’t run as printed it isn’t worthwhile doing any hand-wringing.

Back to the game! There’s just four verbs, EAT, DRINK, SMELL, and GIVE. The game manages a bit of humor even within those constraints; while the most logical thing to eat is the CABBAGE, you can eat anything else as well:

This feels like something out of Thunderland. Maybe because it isn’t a full game with lots of constraints to worry about the author decided to let EAT work as it does.

Drinking the bottle is a loss (or at least, it was once I fixed the source code).

If you EAT CABBAGE the game mysteriously specifies I’M IN LOVE; then you can give the princess a flower.

Now on to the main event! It’s time to Journey to Planet Pincus. Albeit this is a journey where you should temper expectations because, again, Ken Rose is really quite thorough about documenting what every line does, so the type-in can only be so long. (The game itself is listed in the code as solely by Michael Rose.)

Seriously, it explains everything.

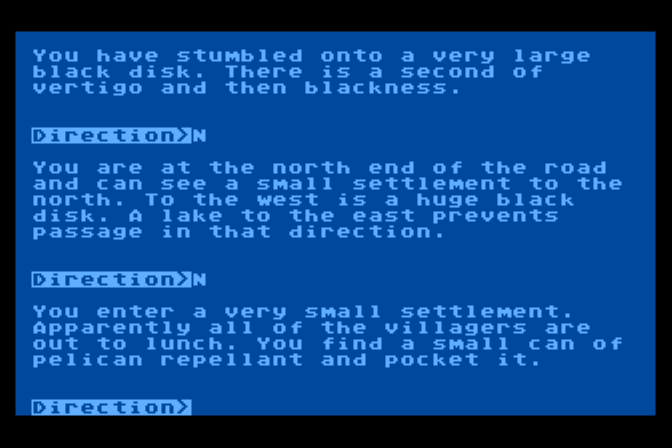

Again, Apple source code isn’t available, but this time a conversion to Atari source is, so I played with that version. The problem with typing-in the type-in is extreme spoilers on how to beat the game, so I’m happy to roll with an operating system change.

There isn’t that much to spoil, though: this is quite intentionally a directions-only game with a tiny map. Remember January focused on monster combat (…odd pick, but ok…) and March focused on a simple parser, but assuming someone who is learning by following along, they haven’t tried making a map yet.

You need to find some dilithium crystals. First you go north and find some pelican repellant, then go south and use it to get the crystals, then go back to the ship and exit. It took me a little longer to solve making the actual map, but maybe something like five minutes?

Maybe eight or nine. I stumbled into the “teleporter” early (see west on the map) so I had two distinct portions that needed to be joined into the larger map once I realized the structure.

Otherwise this is almost literally the simplest adventure possible while still being an adventure.

But: keep in mind the context. This is to illustrate programming a map to someone who hasn’t made one yet. I admit this was a lot of lead-up (and 1000+ words) to get to that, but it’s easy to run across one of these types of games (on Atarimania, say) without context and assume maybe the author just didn’t know what they were doing.

We will of course be returning to Rose’s 1982 column at some point, where the later iterations of the sample games may be a little richer in content.

The source code for the initial two games (which can be cut-and-paste into AppleWin, or an online interpreter of AppleBASIC) are available at my GitHub directory of BASIC source code.