The original Crowther and Woods adventure hits above its weight class. It has all the sloppy edges of an innovator, but there’s a tactile atmosphere lacking in most of the imitations that follow, and I theorize that this is due to the original being based on the actual Colossal Cave in Kentucky, closely enough that it is possible to match the map of the game to the cave. It’s awful easy to link rooms called “cave” together just out of one’s imagination, but harder to match the character of the WINDOW ON PIT, or Y2, or the HALL OF MISTS, all real locations.

The strength of coding and reasonable puzzles didn’t hurt, either, but my general point is that a certain grounding in reality can elevate what otherwise would be a mundane room location.

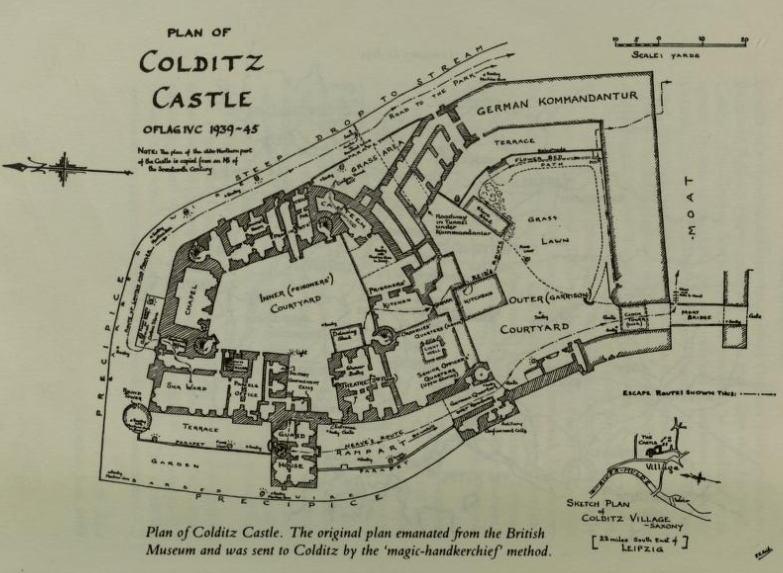

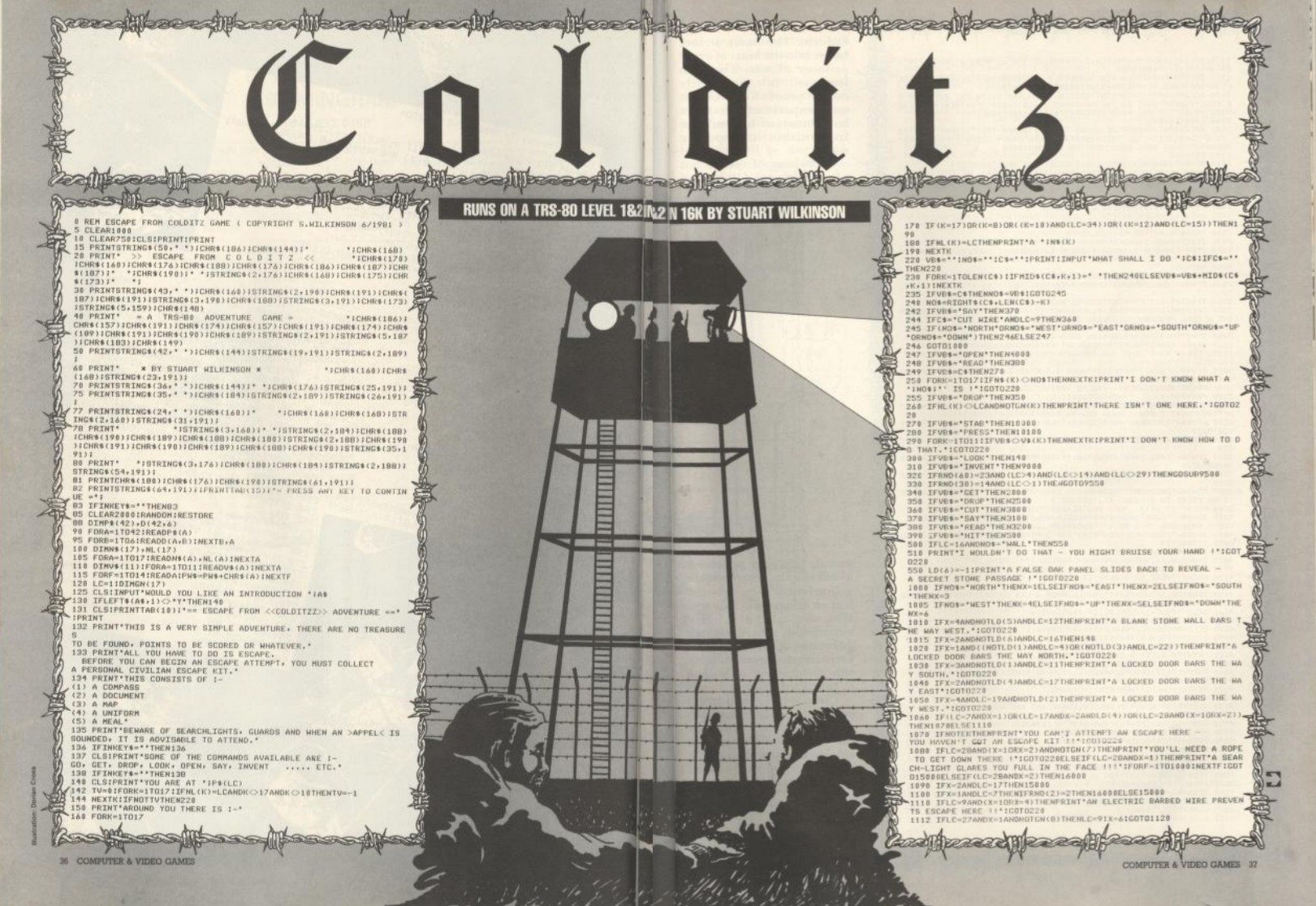

The TRS-80 game Escape from Colditz by Stuart Wilkinson is based on a board game, and the board game was made with consultation of someone (Pat Reid) who lived the experience. So for what qualities the game has, it automatically gets some via the same grounding in reality as Colossal Cave.

Unfortunately — and I regret to inform you, given I wrote two posts worth of buildup — in most other respects, the game is very, very, bad.

At least the title screen is a good rendition of the castle.

The instructions state

THIS IS A VERY SIMPLE ADVENTURE , THERE ARE NO TREASURES

TO BE FOUND ,POINTS TO BE SCORED OR WHAT EVER .

and that before an escape attempt can begin, you need to collect an “escape kit” consisting of a compass, document, map, uniform, and meal. (Compare with the rules for the board game: “The Escape Kit consists of Civilian Disguises, Magnetic Compass, Food, false documents, maps, and money (Reichmarks). For the purpose of this game, documents, maps, and money have been combined together, providing a total of four components to be collected.”)

The opening screen is above. Notice: no room exits, and more or less no description. This holds throughout the entire game. The only way to find out an exit works is to try it out, and even then you may not know, because the game simply reprints the room description if going a direction fails instead of stating outright a particular move is impossible. We’ve seen this before in Arnstein’s Haunted House, which compounded the problem by putting two identical rooms next to each other (so you couldn’t tell you had changed rooms!) Escape from Colditz repeats the same trick.

The Theatre is three rooms. I only found this out very late in my playthrough. I had entered the westmost room, and then tested the exits by typing GO EAST, GO SOUTH, and GO WEST, which of course looped me back to where I started without realizing I was changing rooms! This meant I missed the eastmost room (with a ladder) altogether.

I had found a PASS CARD, a COMPASS, a MEAL, and a TAG that read “DER BEUTELMAUS” fairly early but I was otherwise stuck. I knew I likely needed to go north of the APPEL

THE GUARD ON DUTY STOPS YOU

WHAT IS

YOUR IDENTIFICATION ?

but I was stuck trying “password” phrases, including various permutations of DER BEUTELMAUS. I finally broke down and looked up hints, to find that the prompt was being a continuation of the parser, and rather than the prompt being for what the player would say in response to the guard’s question, it was asking for another parser command, one that had to be typed in exactly.

THE GUARD ON DUTY STOPS YOU

WHAT IS

YOUR IDENTIFICATION ? SHOW PASS CARD

Bravo, game: you found a brand new way to be awful.

Once I made it by the guard I found a KEY and some DOCUMENTS. Combined with the COMPASS and MEAL I was lacking before, I just needed a MAP and UNIFORM.

For the map, I needed to win another epic struggle of getting the computer to understand me.

The MAP is past this door in a tunnel.

For the missing uniform, the game here invokes another nearly unique bad trope, one I’ve only seen in the original Dog Star Adventure. In the earliest type-in version, that game had a supply room where you had to guess at what the room contained and just try to GET stuff (like a BLASTER) and hope you were lucky.

Once I had my uniform disguise, I was able to stride back through with the pass card and make a beeline for the front gate.

Here we come up to the second-to-worst part: there is only a 50% chance the action above will work. (No doubt attempting to invoke the randomness of the board game.) If the action fails, you lose, with no indication it was random chance that did you in.

And yes, I did say second-to-worst. That’s because there’s an entirely different escape route. You remember the ladder from the theater? You can use that plus a rope to try to climb over a wall, but you always get caught, 100% of the time. (This is after going through the work of collecting an escape kit.) You can check Dale Dobson’s writeup for more detail. (He calls it a “bug” but I’m not so sure the game isn’t just trying to be cruel here.)

Looping back to my introduction, despite all the suffering, there is an interesting setting buried in here. The real Colditz has plenty of tunnels and obscure nooks and crannies via the centuries of history, the board game replicates the same thing, and the TRS-80 game tries to do the same. It’s legions off my being able to recommend it to anyone, but there were still moments, like when I first went underground, or I first stepped in the Chapel, that I felt the distant wonder of adventure games.

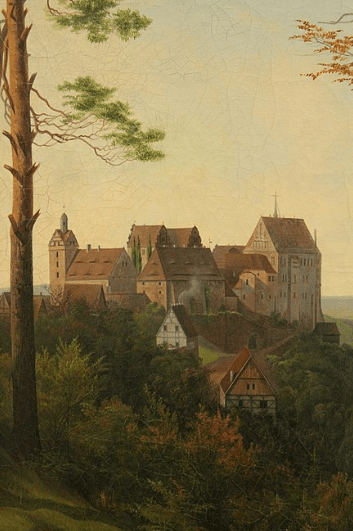

An 1828 painting of Colditz Castle by Ernst Ferdinand Oehme.

I did mention last time there were nine Colditz-inspired adventures — here are the other eight in chronological order —

Colditz (Hans-Peter Ponten, 1981, in Dutch)

Colditz Adventure (Superior Software, 1983)

Colditz! (LVL Software, 1983)

Castle Colditz (Felix Software, 1984)

Colditz (Phipps Associates, 1984)

Mission Secrète A Colditz (CPC, 1985, in French)

Colditz Escape (Adventure Probe, 1986)

Colditz (Uto, 2010, in Spanish)

— and yes, the existence of the Dutch Colditz means it may have come first, but I have a few question marks to resolve with that game before I can say more.

Having gone through mounds of research for a profoundly terrible TRS-80 game, I can say there is good reason why Colditz spawned so many adventures; everything is naturally self-contained, the plot is clear and dramatic, and the interaction for most escapes was based mainly on cleverness-with-items rather than smooth-talking the guards (see: Reid’s failure to bribe a guard in his first escape attempt). It also used to be part of the cultural landscape; there was a time the name Colditz gave instant recognition.

And perhaps it still has instant recognition now in some places? A question I put to my trusty readers.

The game was published in the September 1982 issue of Computer & Video Games magazine.

Captain Yule also arranged music for the prisoners’ orchestra. The strains often drowned out preparations for breakouts or distracted guards when escapes were in progress. On one occasion, the music started or stopped to signal two escaping prisoners on the whereabouts of sentries who were in view of the prisoner musicians. And a space below the theater stage was used by four escapees as an exit toward passageways leading to freedom.

From the obituary for Lt. Col. Jimmy Yule who died in 2001. As a prisoner at Colditz, he operated a hidden radio. The secret radio room was discovered in 1993 (!) and still had Yule’s old codebook. It included a poem: “Back in London, here we are / Back to clubs and caviar. / Back to Covent Garden’s fruits, / Back to 50-shilling suits.”