Let’s do something a little different and have one of today’s co-authors introduce the game. This is a video from 5 years ago when Al Lowe was selling his source code from his days at Sierra. He included some pre-Sierra materials from when he was co-founder of Sunnyside Soft.

…and the floppy disk, that we copied ourselves on my neighbor’s pool table. We set up an Apple II, open the lid of it, blew an electric fan at it, and put in five disk drive cards and pairs of disk drives … we ended up producing hundreds of games in one evening on my friend’s table.

Prior to changing professions to software, Al Lowe was a veteran music teacher. A few years before, he had been caught ill with chickenpox and in isolation he was able to try out a DEC timesharing terminal remotely hooked up to a PDP-11/70.

This gave him the computer bug, enough so he bought an Apple II, and used it for keeping track of band information. When going to a band conference in the summer of 1982, he also went to the National Educational Computing Conference held the same week.

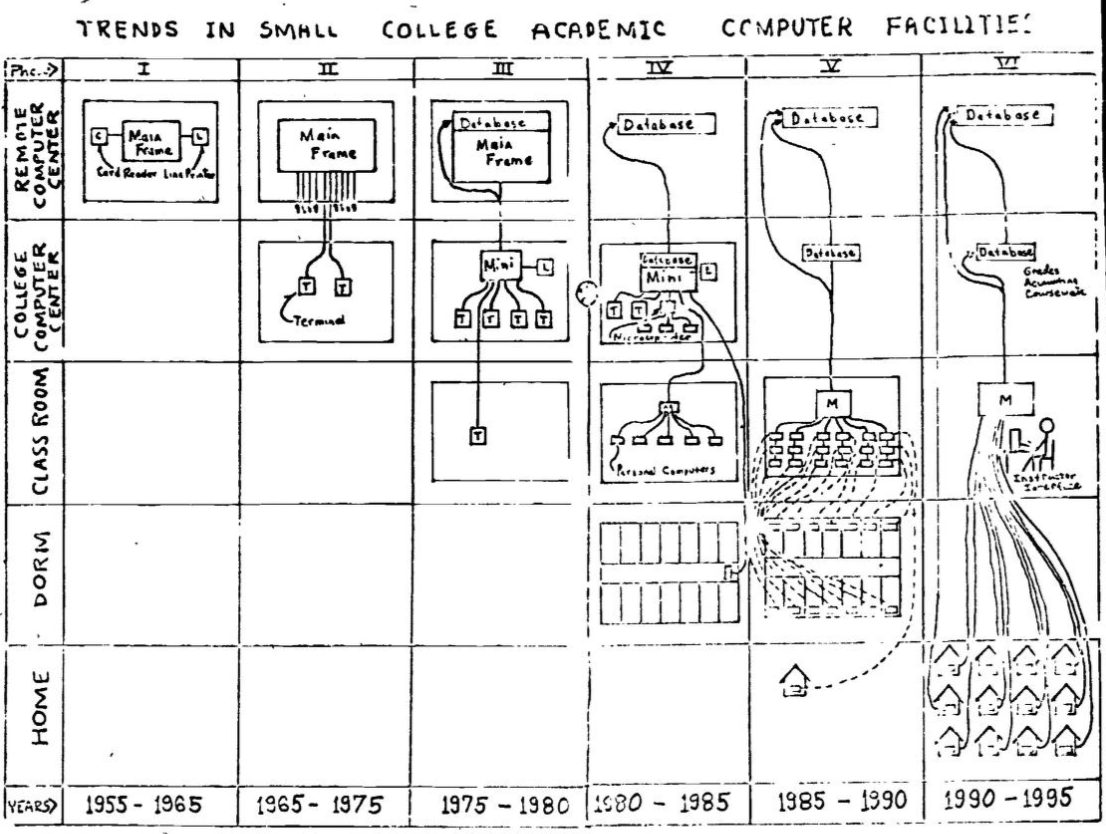

From the proceedings of the previous year’s NECC conference.

He was unimpressed, saying in a later interview:

Most educational-software material on the market today could be done in a workbook … what kids need is brain-world coordination.

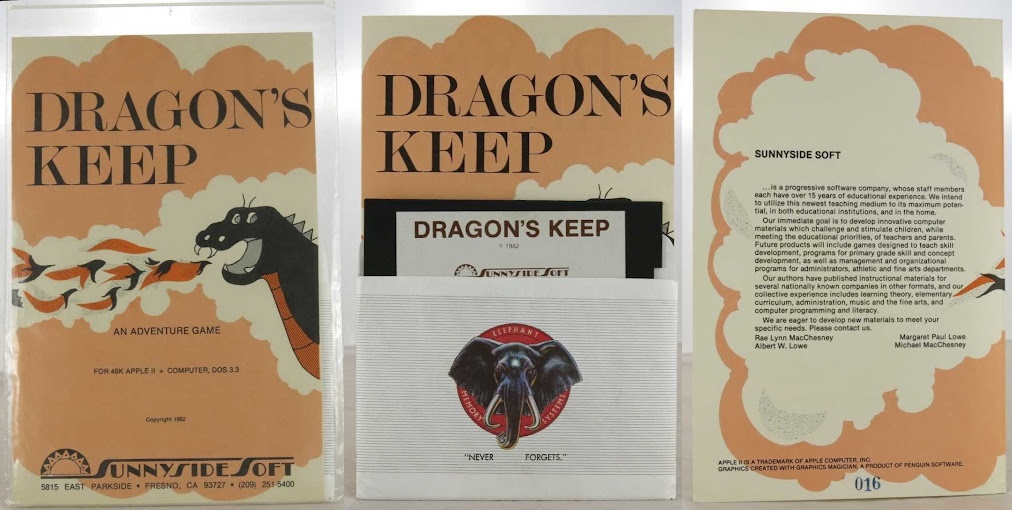

He felt he could do better, and he (with his wife Margaret, and his neighbors Rae Lynn and Mike MacChensey, all in education) founded Sunnyside Soft with Dragon’s Keep and Bop-a-Bet as starting titles. Bop-a-Bet is a maze game where you need to zap letters in alphabetical order, and Dragon’s Keep is an adventure game with menus rather than a parser (more on this later).

For art the team used the graphics software from Penguin:

In Dragon’s Keep, I used paddles! They were left-over from Pong – each paddle had a knob that could turn and a button to press. You held it in one hand, press the button with your left thumb, and turn the knob with your right hand. Your opponent had another paddle just like that. Since I couldn’t afford a joystick, I used the paddles to create backgrounds. You would turn one paddle to move the cursor up, and turn the other paddle to move the cursor across, and then you would press the button to draw the picture. Picture Etch-A-Sketch with a Paint program.

In early December, the company had a booth at Applefest in San Francisco.

Margaret Lowe demonstrating Bop-a-Bet. From Softalk January 1983.

At the same event was Ken and Roberta Williams, with a large space at the entrance devoted to Sierra On-Line. They had just added the “Sierra” to their name. Allegedly this was to avoid overlap with another company, but also, quoting marketing director John Williams, the original name of the company was “generic as could be and dull as dishwater”. The booth had a mural of a Sierra waterfall to announce the change. Richard Garriott was there, showing off Ultima II (now a Sierra product) while dressed as Lord British.

Of course, such events are for networking as much as sales. According to Steve Levy in his book Hackers:

Ken tried to throw himself into the spirit of the show, and took Roberta, looking chic in designer jeans, high boots, and a black beret, on a quick tour of the displays. Ken was a natural schmoozer, and at almost every booth he was recognized and greeted warmly. He asked about half a dozen young programmers to come up to Oakhurst and get rich hacking for On-Line.

As part of this schmoozing the Sierra founders came across the much smaller Sunnyside booth, and were impressed by how the look of Dragon’s Keep resembled a Sierra title. This connection led them to publishing the titles under the Sierra label.

As Sunnyside ceased to exist soon after this, copies are rare; it is possible the “pool table copies” were the only ones ever made under that label.

Three pictures of the same copy, from Larry Laffer dot Net.

The back of both Sunnyside games came with a “mission statement” which is worth quoting in full:

SUNNYSIDE SOFT is a progressive software company, whose staff members each have over 15 years of educational experience. We intend to utilize this newest teaching medium to its maximum potential, in both educational institutions, and in the home.

Our immediate goal is to develop innovative computer materials which challenge and stimulate children, while meeting the educational priorities, of teachers and parents. Future products will include games designed to teach skill development, programs for primary grade skill and concept development, as well as management and organizational programs for administrators, athletic, and fine arts departments.

Notice the “organizational programs” — they were clearly thinking of the software Al Lowe already wrote for music classes.

Our authors have published instructional materials for several nationally known companies in other formats, and our collective experience includes learning theory, elementary curriculum, administration, music and the fine arts, and computer programming and literacy.

We are eager to develop new materials to meet your specific needs. Please contact us.

Rae Lynn MacChesney / Margaret Paul Lowe

Albert W. Lowe / Michael MacChesney

Sierra added a map and stickers to Dragon’s Keep enhance the appeal, and included a parent guide which outlined specifically what skills were being taught.

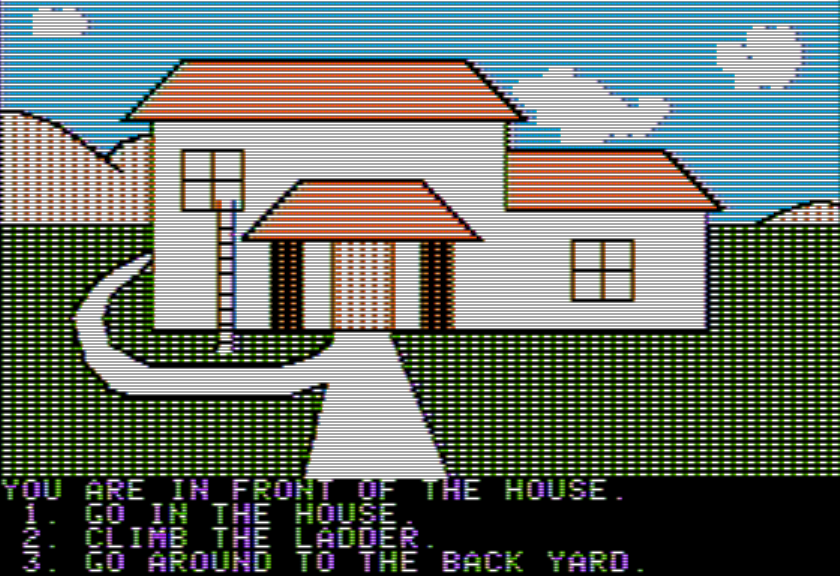

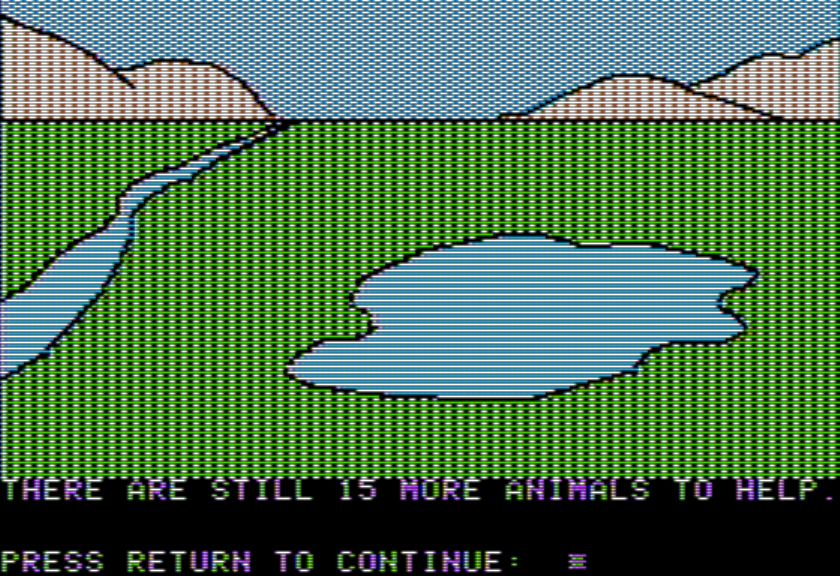

In the game, a magical dragon is holding 16 animals captive in and around its magic house. The player must find each animal and set it free. Sometimes the dragon appears and won’t let an animal go. The player must then leave the scene and return later when the dragon has gone.

Dragon’s Keep is designed to help your child develop reading comprehension skills. These skills include identifying details, making inferences and drawing conclusions.

The stickers correspond to the 16 missing animals.

From The Sierra Chest.

Navigation and action is all done via a menu system. We’ve seen this with Kadath in 1979 so isn’t the first appearance of this kind of thing, but it’s still pretty early.

The menu is slightly out of the ordinary, anticipating a child who has never touched a keyboard before. There are at most 3 options at any time, and even though the options are numbered, you don’t use number keys.

Instead, you move a cursor to the left by hitting the space bar, and then you hit enter once the cursor is at the option you want. This is at the level of games for children I’ve seen where the goal is to push the C key, and the authors anticipate this will present some challenge level. I personally would have included the numbers as a secondary scheme but they clearly didn’t want to muck up the directions.

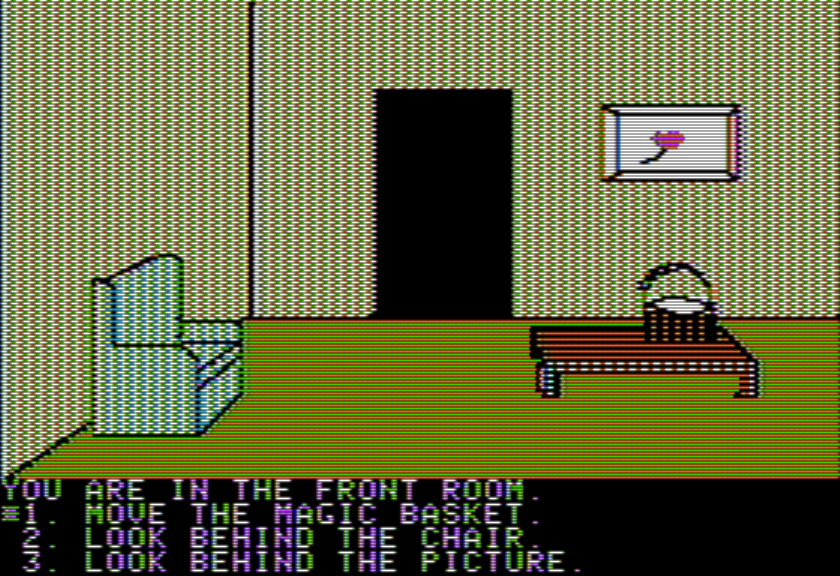

This shows going into the back yard, and presents one of the major oddities with the game: map traversal isn’t all two-way paths. Notice there’s no option to go back to the front of the house, so someone who wanted to reconsider and climb up the ladder instead now doesn’t have an option.

Even if you think — well, I’ll go back in the house, and then I’ll be close enough I can go up the ladder, no, you get entirely different options:

(There’s a dog behind that chair! Mean old dragon.)

Eventually the map kind of makes sense, but if the goal is to teach map skills, this is a curious way to do it. The navigation reminds me more of regular-gamebook style, where sections often get elided or skipped over; that is, if a section of map requires you travel 3 sections to get to a dead end, the game won’t necessarily have you take every step back, because in terms of narrative it can feel strange to read the exact same texts in reverse order. There are books that do this anyway; Scorpion Swamp of the Fighting Fantasy series has an “open map” so has more adventure-style map movement, but that translates to sections that look like this:

290

You can see signs that others have walked this way recently. Ahead is another clearing. This is Clearing 26. If you have been here before, turn to 323. If you have not been here before, keep reading. As you enter the clearing, an arrow whizzes past your head. You see three mangy-looking SWAMP ORCS armed with bows. The other two let their arrows fly. If you have the Golden Magnet charm, turn to 83. If you do not have it, turn to 151.

Notice the “if you have been here before” failsafe (which is made even more complicated here because you’re allowed to flee from this encounter, so section 323 might kick you back into combat).

For example, the game has a school. To get to the school from home you go to the back yard (with the fish), then follow a river…

,,,then go to the mountain, which happens to have a train…

…then from the train station go to the bus stop…

Dog number 2. Notice the stickers show brown dogs and these dogs are white.

…and finally from the bus stop go to school.

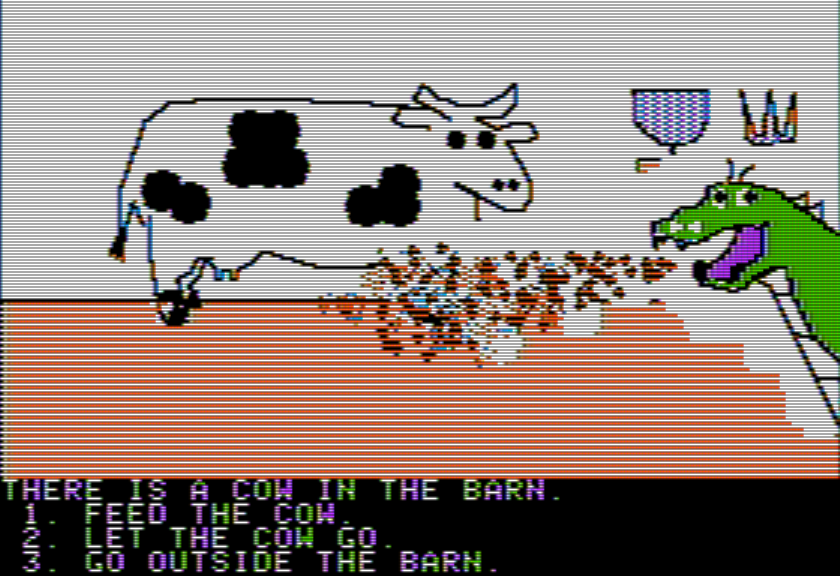

The dragon at that last stop represents the other element of the game: in some scenes the dragon will be there at random. It really is truly a random dice roll if the dragon shows up, plus the dragon will just stop you from rescuing an animal in the immediate scene; you can leave and come back. (Unless you leave the school. In which case you get back sent to the front of your house, and you have to take all those steps to return.)

The dragon shows up in scenes, not rooms, so if you’re in a library and pick up a book to read, the dragon may show up at the book but won’t be in the room.

Ah yes, the “hen is at the station”. One of the other quirky things about the game is that it generally expects you to think about where animals might be where you still don’t have the stickers placed and go where the animals might be. To problem is quite a lot of the animals are in odd locations so that logic doesn’t work that well. If you’re still looking for a rabbit, and you remember you saw a top hat you neglected to look inside, sure, that’ll work:

A calf? At the zoo.

In the end, the game is more “about” the skill of lawnmowering through all the story options. The hen (hinted at in the book, the only animal with this treatment) is the most curious find, as you locate it by taking a nap at the train station.

Mind you, the odd directionality isn’t that bad, and parts of the map (as given at The Sierra Chest) do direct around like normal, although I should make one last point that there’s not really a geographic sense to any of this — I have no idea what the real layout of the house is.

In the end, the game requires enough reading I’d say it has legitimate educational purpose, but I think modern children might find the overarching idea too simplistic.

In historical terms, other than uniting Sunnyside with Sierra, the interface was noticed at the time as a potential new direction for adventures. Jay Lucas had an extended 1983 review in Infoworld which begins with an extended rant about his difficulty with text parsers:

I used to be hooked on adventures, but like most of my computer colleagues, I closed my adventure era because of reoccurring frustrations. The programs have limited vocabularies, and I often had to go through four or five synonyms to find the word acceptable to the machine. Once past the word barrier, I was still limited to the choices of responses envisioned by the program author.

He then goes on to do a mock-example, then point out that the game “cleverly avoids” such issues.

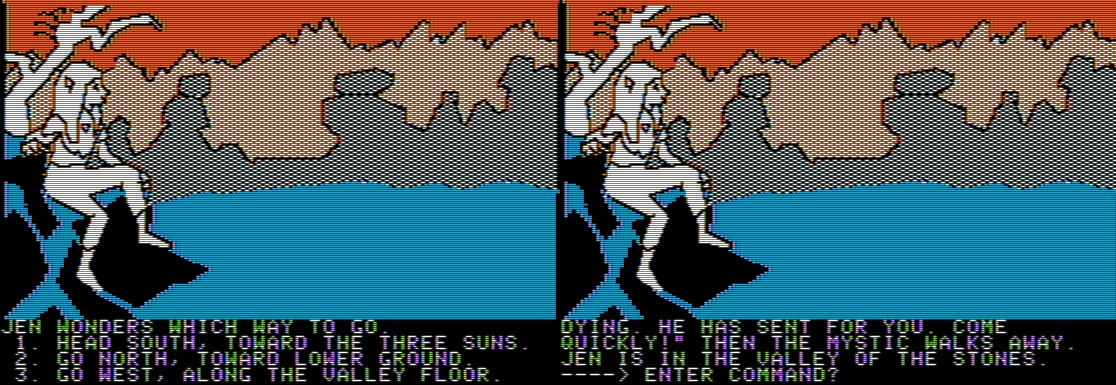

Of course, this is a game which isn’t even trying to have puzzles. It was rather harder for people at the time to imagine what a “crunchy” game would be like with a menu system (Kadath pulled it off but had a wild navigation gimmick that wouldn’t work elsewhere). At least Sierra didn’t drop the notion, as the Sunnyside crew followed up with Troll’s Tale in 1983. Perhaps the most interesting use was taking the text-parser game The Dark Crystal (published early 1983) and converting it for a menu system in Gelfling Adventure.

Menu version on the left, parser version on the right.

Up next: a con-artist anthropologist, and the game based on their work.