To be clear from the start, I am writing today about an extremely obscure VIC-20 game from 1983, but to do justice to the story, I need to start just a little farther back–

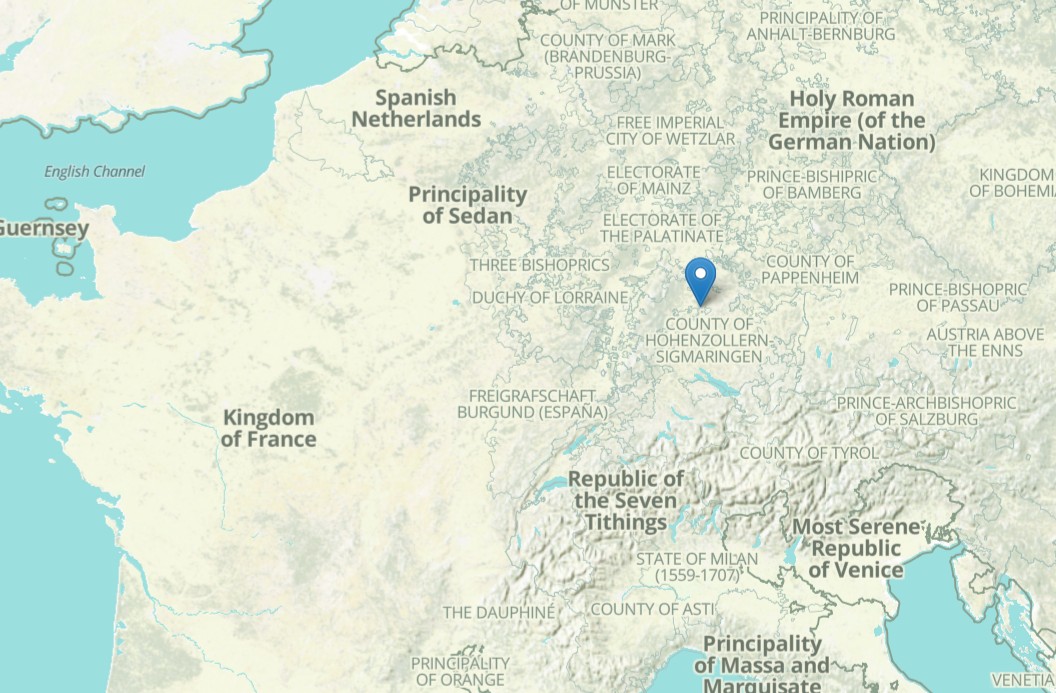

The University of Tübingen. Located in modern-day Germany, depicted here in the early 1600s.

While the German Johannes Kepler is now one of the most famous names in the history of astronomy, his work reached the scientific world in a slow burn. His first law of motion, describing the orbits of planets as ellipses (contra Copernicus and his “circles with epicycles”) was published in 1609 but not accepted until many years later.

Part of the issue was simply the quality of the astronomy data being collected. The obsessive work of Tycho Brahe (another one of the astronomy greats) was compiled by Kepler himself over a period of 22 years into the Tabulae Rudolphinae, a set of star charts and planetary tables with accuracy far superior to that which came before. Kepler was not a fan of the labor, writing in one letter:

Do not sentence me completely to the treadmill of mathematical calculations, and leave me time for philosophical speculations, which are my only delight.

His lack of enthusiasm for mathematical tedium was shared by another German polymath: Wilhelm Schickard. (By “polymath” I mean he was a Professor of Hebrew, Oriental Languages, Mathematics, Astronomy, and Geography.) Both Kepler and Schickard had affiliations with Tübingen University and were sometimes collaborators. We know from letters between the two that they had discussions on the labor-saving invention known as Napier’s bones (1617), rods intended to allow easier calculations; these rods, however, were still entirely manual work, needing to be placed against a frame.

Schickard got the idea: what if he could make a full “calculating machine” akin to Napier’s bones that would work automatically, like (literal) clockwork?

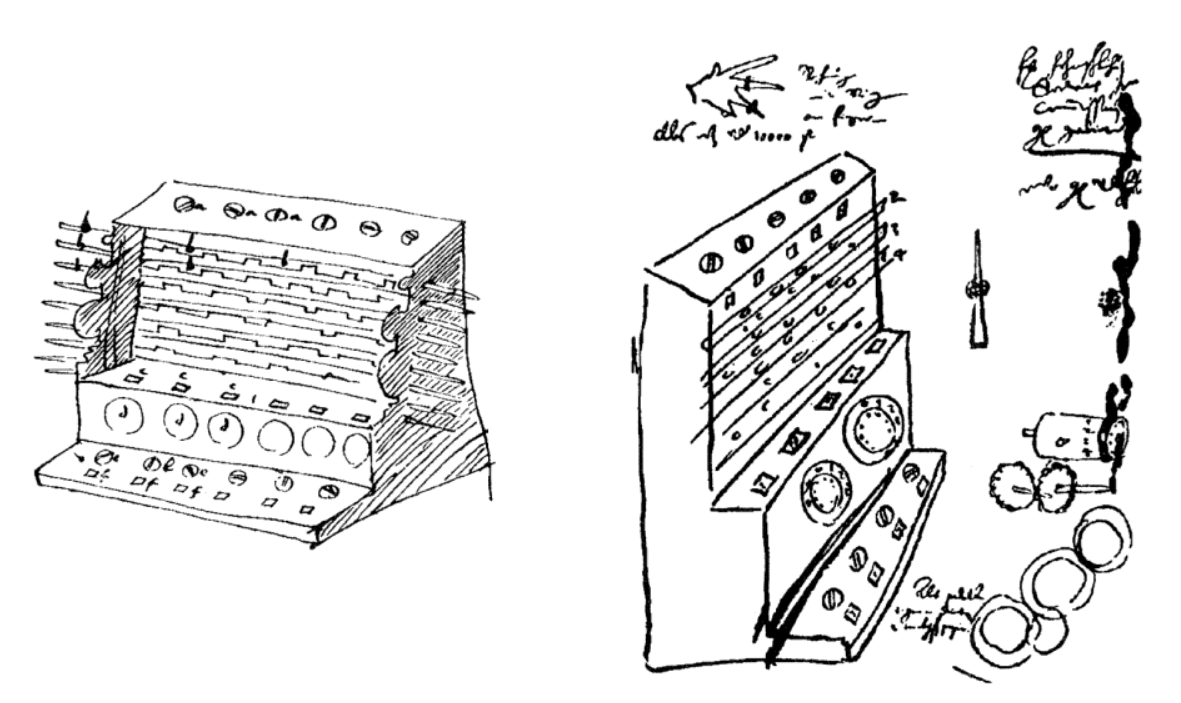

He got a device working and described it in some detail to Kepler in a letter, including a picture.

The device includes actual Napier bones in the mechanism, and uses an “accumulator wheel” that would cause a digit to go up by one. This involves a tooth of the wheel needing to move exactly 360 / 10 = 36 degrees and while it was unclear what exact method Schickard used, he likely had a spring set up to allow the internal gears to stop at specific points. It had the issue that an overflow (999999 + 1) could actually damage the gears.

Modern replica, via the Computer History Museum.

Unfortunately, the picture in Kepler’s letter was not found until much later (it was on a separate paper being used as a bookmark) so despite Schickard being the first to create an automatic calculator he was not influential. Instead, the icon for kicking off automatic calculation was Blaise Pascal, yet another polymath, French rather than German. He obtained fame in mathematics, science, and religion (his biggest contribution in science being to prove that pressure changes with altitude, hence the unit of atmospheric measurement being a Pascal).

From a lithograph of Pascal after a painting by François Quesnel the younger.

Blaise was born in 1623, hence the story now is squarely in the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), which started to be the utter ruin of all of Europe. The Pascals (father: Etienne; mother: Antoinette) were a rich family that lived in the small town of Clermont. Etienne had the aristocratic job of “tax collector”. (Blaise did not mention his mother much as she died when he was three.) Etienne decided (with Blaise at age nine) that it was better to be closer to Paris where intellectual and political life was blazing. Etienne sold his tax post and invested in government bonds instead, which would normally give the Pascals a generous income while in Paris. However, the Thirty Years’ War lasted (squints) a long time, and the government cut back on their interest rates of those aforementioned bonds while spending vast amounts on war. Etienne made a protest as part of a group; displeased, the King’s Chief Minister (Cardinal Richelieu) ordered those protesting arrested. Etienne ended up fleeing Paris (back to Clermont) and leaving his governess in charge.

Richelieu on the Sea Wall of La Rochelle, painted in 1881 by Henri-Paul Motte. The Siege at La Rochelle (1627–1629) ended up being a major victory for the Royalists. It was one as well for the Cardinal, who was trying to centralize power to the King.

Events turned by a stroke of luck: the wife of Louis XIII, Anne of Austria, was finally pregnant. This, in best Louis XIII fashion, was cause for great celebration. One of the invitees was Jacqueline Pascal (aged twelve) who was known for acting and reciting poems. She made an appearance during the event and talked to the Cardinal while there, getting a promise of rehabilitation for her father rather than arrest. This ended with his father being given an appointment as tax collector of Rouen, capital of Normandy.

To be clear, this was only halfway-generous on Cardinal Richelieu’s part. Etienne still had angered the Cardinal. His place of appointment was not an easy place to collect taxes. Its location near the Channel (and former affiliation with the English king) made it a prime spot for English and Scottish Catholics and it had a general reputation for chaos.

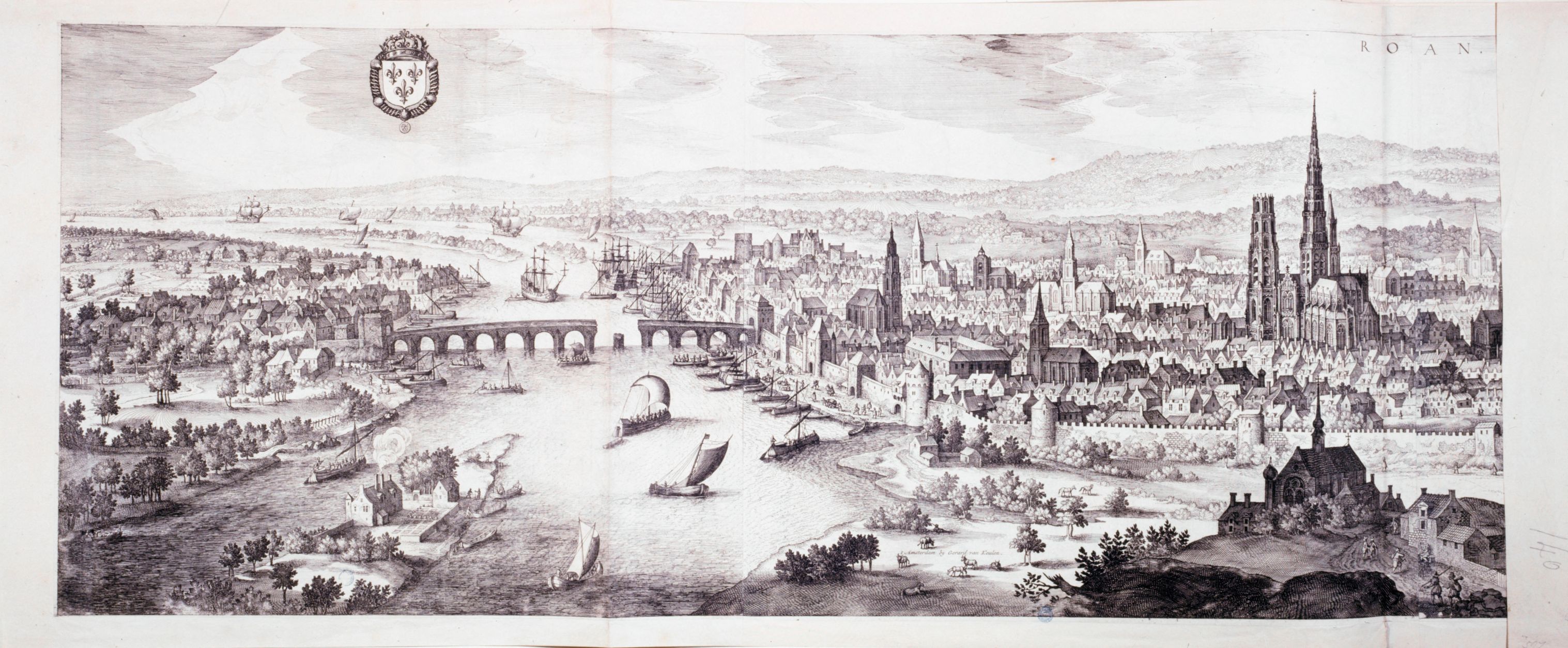

“Roan”, plan de la ville de Rouen, 1620. From Les musées de la Ville de Paris.

The calculations for tax collection were onerous. Blaise was recruited to help, leading the polymath in 1642 to devise an instrument: the Pascaline. It resembles Schickard’s device in using gears although it is addition-only (Schickard’s could do subtraction). On the other hand, Pascal’s device allowed gears in increments other than 10, making it better suited for financial use (example: 12 deniers = 1 sous).

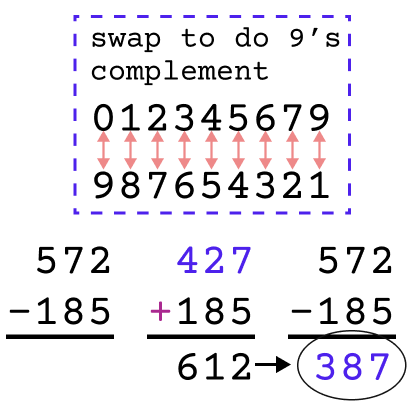

Since there was no built-in subtraction function, it was instead done with the 9’s complement method.

Because it is genuinely important for the story, a brief explanation how the 9’s complement method works. Suppose you want to do 68 − 34, but want to do it with addition rather than subtraction. Take the first number (68 in this case) and subtract it from 99; except, you don’t need to actually do the subtraction! All 0s will swap with 9s, all 1s will swap with 8s, all 2s will swap with 7s, etc. So 68 − 34 turns into 31 + 34. Do the resulting addition; with the example you get 65. Then take the end result and do the “subtract from 99” trick (or rather, digit swap) and you get 34, which is the correct result.

Another example. 572 swaps digits to be 427. Add and you get 612, then swap back and you get 387, which is the result of subtraction.

While Pascal wrote a pamphlet explaining the system…

The length and difficulty of the ordinary methods led me to consider quicker and easier ways in order to relieve me of the complex calculations I had done for some years regarding positions you honored my father with in the service of His Majesty in Upper Normandy.

…and he made multiple Pascalines over his lifetime, some which still exist today, it was expensive and only available to the very rich. Still, this method led to a general approach to automatic calculating devices which lasted much longer than you might suspect. Lurking closer to our ultimate goal, in the 19th century, the comptometer was designed very much like Pascal’s mechanism but with straight rods rather than rotating dials. (The prototype used meat skewer rods in a macaroni box.) It even still used the 9’s complement method.

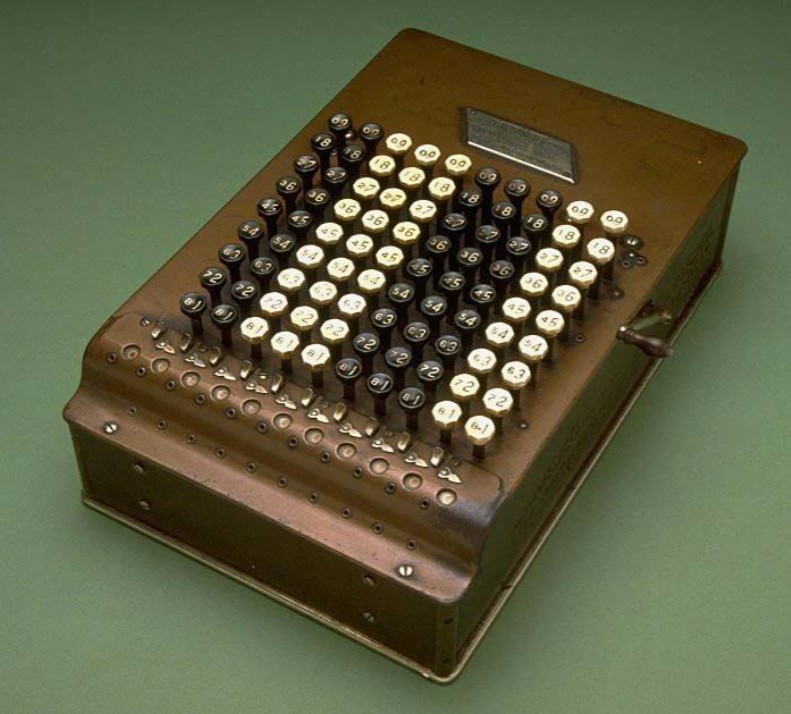

A 1909 model, via the Smithsonian.

The buttons of the device have two numbers on them; the smaller numbers represent the 9’s complement, so a fluent operator can think in terms of swapping the 9’s complement quickly. What I mean by this is that it wasn’t as terrible a system as it might seem to modern eyes, and the device had a fantastic feature: you could press multiple buttons at the same time. That is, on a standard electronic calculator, you might need to press 4, 7, 3, and 2 in sequence to get the number 4732, but an operator of a comptometer doesn’t have to wait: they can press all four buttons simultaneously. Furthermore, the 9s complement system means that with number-buttons only a fast operator can rapidly move through additions and subtractions in mixed order without slowing down to specify what operation they’re doing.

All this is relevant to the company of Bell Punch Co., Limited, founded in 1878 in the UK, which obtained the patent rights to a ticket punch machine already in use in America. It was used for trains to — as the name implies — punch tickets; it was generally the case beforehand that people paid a flat fee for an “area” rather than their actual distance travelled. With the punch tickets, you can have an exact number of stops marked automatically.

In 1924 they expanded into dispensing movie tickets (by purchasing the company Automaticket); in 1929 they expanded again into race betting tickets. (In between these, they formed Control Systems, Limited as a consolidation company.) Bell Punch tried putting an adding mechanism to go along with one of the ticket mechanisms, and got the rights to an adding machine design (the Petometer, 1933) in the process. They soon began creating just the adding machines by themselves. The video below shows the “Plus Adder S” manufactured from 1936 to 1940 based on the Petometer model.

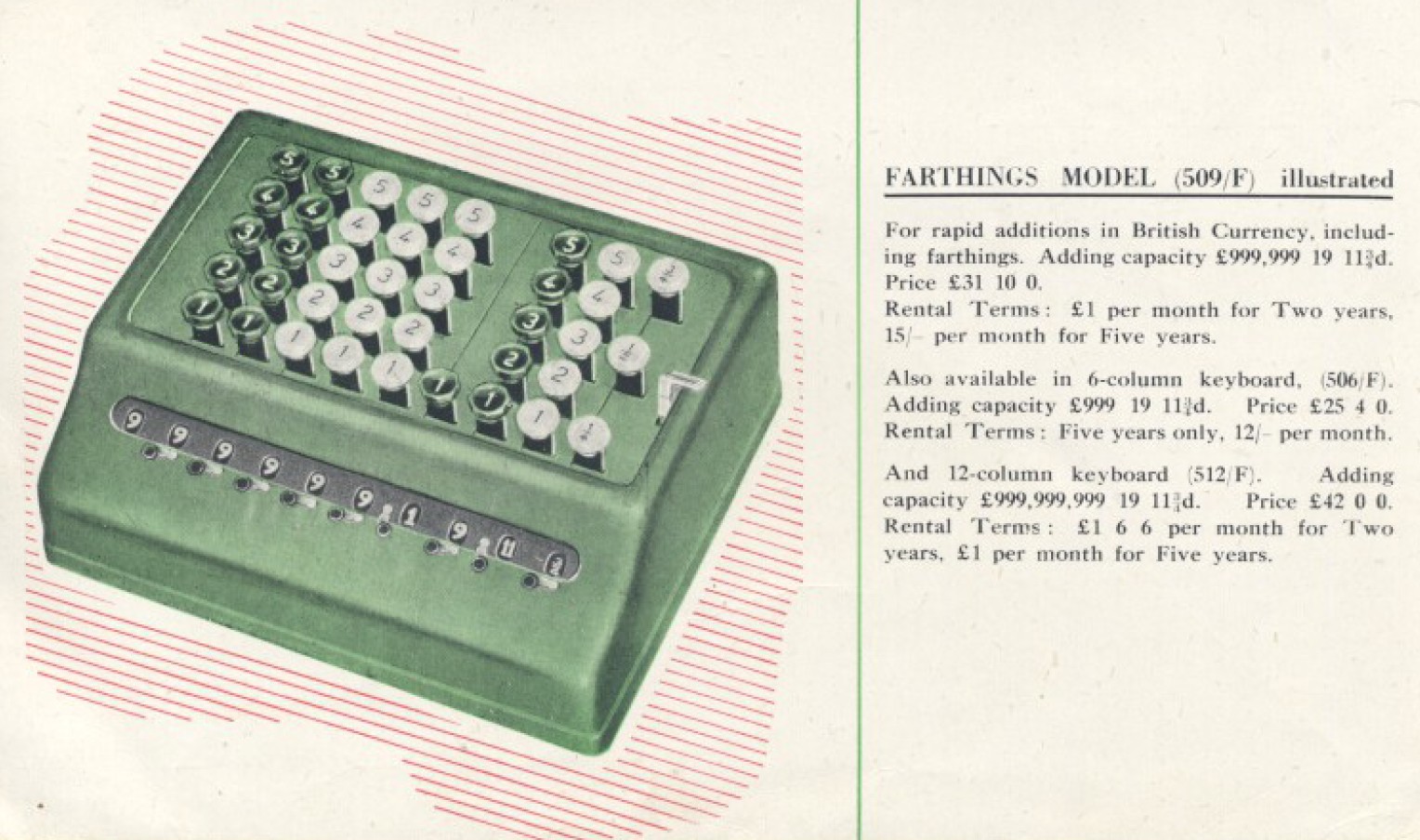

During WW2 they made a subsidiary brand, Sumlock, specifically for the manufacture of calculating machines. A 1943 ad highlighted the “more-work-less-staff-problem” being faced during the war. After the war they pushed even harder into the calculating space.

From a 1948 brochure.

They consequently were poised to hit a remarkable milestone of 20th century technology: they made the first fully electronic desktop calculator.

The genesis of Sumlock’s device (code-named ANITA) started at Birkbeck College in London, where Andrew Booth led one of the groups in the UK looking to build digital computers, and due to limited resources tried to think small, embarking work on an Automatic Relay Calculator (or ARC).

December 1946. Kathleen Britten, Xenia Sweeting, and Andrew Booth. Kathleen Britten was soon to be Kathleen Booth.

He visited the United States for six months, including two very important meetings. One was Warren Weaver of the Rockefeller Foundation. who was interested in funding a computer project as long as it led to research in “natural language translation”. (Odd for a calculating device, although Birkbeck College ended up becoming a center of automated language translation research.) Andrew also met with von Neumann at Princeton; the ARC was consequently redesigned with von Neumann architecture and Kathleen and Andrew wrote a paper about the possible methods of producing such a computer.

This design was picked up by Norbert Kitz who was a graduate student at the college in 1950.

I was collecting data on the older types of conventional calculators for an introduction to my dissertation on digital computers. While studying those old calculators in the Science Museum, the thought struck me that there was actually one more important page to be written in the book of their history. I had some knowledge of electronic digital computers and it seemed to me that it must be quite possible to use this knowledge for the construction of an electronic desk calculator.

He thought about such a device for some time but it wasn’t until 1956 that he met with directors at Control Systems; Sumlock was still busy at work making giant mechanical machines with 9’s complement markings on the buttons but they were keen on forming a new electronics department; by now Kitz had worked on the Automatic Computing Engine (originally Turing’s design) so had plenty of computer experience. Kitz not only was concerned with the fundamental mechanics of the arithmetic calculation, but he also needed to design the keyboard and the method of display (as prior to all-electronic calculators the displays were mechanical). As Kitz points out in an interview, “our greatest difficulty” was keeping the price down; they were aiming for the £350 to £400 range rather than the usual £50,000 for a computer.

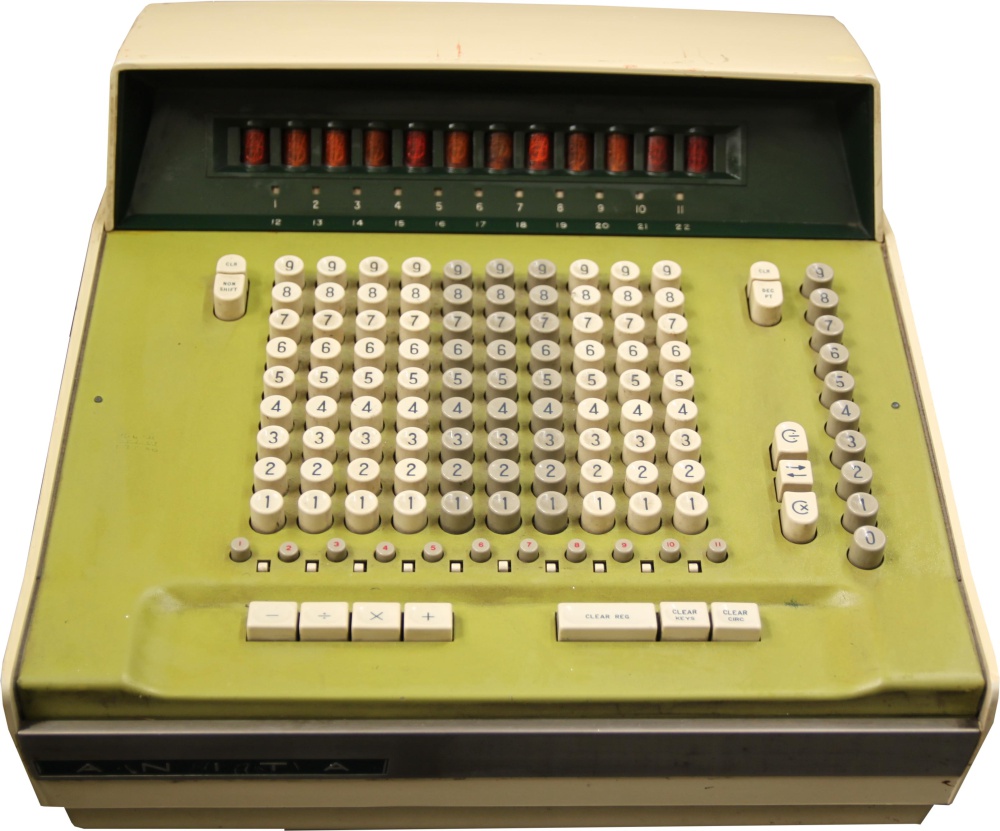

Sumlock introduced their Mark 7 and Mark 8 fully electronic desktop calculators at the Hamburg Business Equipment Fair in 1961, and started selling in 1962, beating everyone else to market. (Sharp, for instance, had Atsushi Asada lead an R&D group in 1960 towards that goal, but they weren’t able to announce the fruit of their labors — the Compet CS-10A — until 1964.)

The follow-up Mark 9 from 1964. Notice how it still follows the form of the original Comptometer, which was itself based around the mechanics of the original Pascal device. Via the Centre for Computing History.

By 1970 (now owned by a new company called Lamson, with Kitz still in charge of calculators) they were at the peak of the UK market.

The company claims to have just under 50 percent of the U.K. market, a market that is expanding. Sales are mainly in the U.K. but outlets do exist overseas through distributors.

A March 1970 market report states they “doubled” their unit sales even with “pressure from competition supported by the full weight of the Japanese electronics industry”. However, Sumlock’s mainstay was the business industry and started selling calculators of other companies in order to fill niches.

Mostek introduced a “calculator on a chip” in 1971 and companies like Texas Instruments soon after introduced their own. (In the UK, that is — Texas Instruments had the first calculator chip to market worldwide, it was used in Japan.) Sumlock tried to jump into the fray getting a chip from Ferranti (which failed) but they ended up going with Rockwell in 1972. Quoting John Lloyd, Chief Engineer:

In 1972 Rockwell, the American defence company, approached us with an offer to put all our calculator circuitry on to one chip. Previously we had always bought from British suppliers because of the need to keep close technical back-up of these suppliers in a high-tech industry. It was a change of policy which was to prove fatal.

Development was started and the prototype of a pocket calculator was produced, the ANITA 800. I was then chief engineer of Sumlock Anita Electronics and Norman Kitz was technical director of the Bell Punch group. He came into my office looking very shaken and put the prototype pocket calculator on my desk and asked what I thought of its sales potential. I said that I thought that with good production engineering we could get the cost down to about £25 and sell a million on the home market and the sky’s the limit for export. ‘Yes I agree with that John’ he said, ‘I have just shown it to our M.D. and he can’t see a market for it’.

The prototype was fully engineered and could have been in production in weeks, but it lay in a drawer of Kitz’s desk for months.

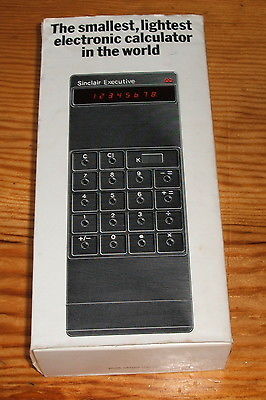

Then Clive Sinclair brought out his pocket calculator. The sales director rushed into Kitz’s office in a panic asking what could we do about it. Kitz opened his drawer and said ‘We can do this’.

Sinclair had beaten the company to market with their Sinclair Executive; as Lloyd claims, “our engineering vision was not matched by our management’s vision”. According to a report from The Times, in 1972 Sumlock went from £1.1m profit to £290,000 loss. Rockwell ended up buying Sumlock in 1973 (separating it from Bell Punch, who was still producing ticket devices, tax counters, and cash collectors); both Kitz and Lloyd stayed with the Bell Punch. Prices of calculators started to plummet as there was a race to the bottom; by 1976 Texas Instruments was able to sell a scientific calculator, the TI-30, for a mere £14.95.

Sumlock still had plenty of expertise and could have diversified into other office machine areas (like word processors) but not long after the sale, Rockwell got a NASA contract for the Space Shuttle and started to lose interest in their foreign investments. Everyone in the main company was “made redundant” by July of 1976 and the various branches worked out splitting off into their own franchises.

Branches tended to land on computer sales; the 1980 Commodore PET price list includes Sumlock Bondain (London), Sumlock Tabdown (Bristol) and Sumlock Electronic Services (Manchester). Even when selling calculators they diverged to other brands. Sumlock-Bondain, as reported by Practical Computing, originally kept selling Sumlock calculators but eventually went to Texas Instruments and Hewlett-Packard.

All this finally leads to the Manchester branch, run by Mike Pomfret. Rather than just being reduced from a mighty engineering company to a sales company, they decided to produce their own software line under the name Sumlock Microware. Mike’s son, Tony Pomfret, was working at the store when he got recruited by Ocean (located “just down the road” from Sumlock) and Tony even makes an appearance in the infamous Commercial Breaks documentary featuring Ocean succeeding and Imagine failing utterly, the latter frittering away money on a game called Bandersnatch.

Retro Gamer: In the programme, you are shown working on Hunchback II, and in one scene, the whole team is sitting around a table, discussing the game’s design. Is that actually how it worked?

Tony Pomfret: That was utter bollocks. It was all staged. I did that game on my own.

Imagine also crosses paths with Sumlock in 1983, as Sumlock’s products included a clone of Frogger called Jumpin’ Jack for VIC-20 (every British company had a Frogger clone, it seems) and a year later Imagine also accidentally hit a nameclash by calling their C64 version of the game Jumpin’ Jack. The two companies managed to work on a plan where neither name would be changed but when Sumlock released their C64 version of Frogger, they called it Leggit.

For today we’re concerned not about C64 games, but VIC-20 games.

From the Centre for Computing History.

Sumlock released a set of games they called a Puzzle Pack written by Kew Enterprises, like Rainbows (“complete the series by typing in the next three letters”), Knight’s Move (“fill all squares of the chess board starting at the marked corner using the knights’ move”), and Graphic Twister (“rearrange each bottom square to look like the top display”). Their ad copy gives a little clue who the proprietor of Kew Enterprises is.

A compendium of six intriguing puzzles, games and IQ tests for the unexpanded VIC20. Specially written by an expert in puzzles to be both entertaining and educational for all ages and abilities. Programs include: ORBITS, KNIGHTS MOVE, GRAPHIC TWISTER, RAINBOWS, SLIDE PUZZLES, DIGITS.

The “expert in puzzles” plus educational aspect make me think we’re dealing with yet another math schoolteacher turning to games, but that’s just a guess (the address of the company is residential).

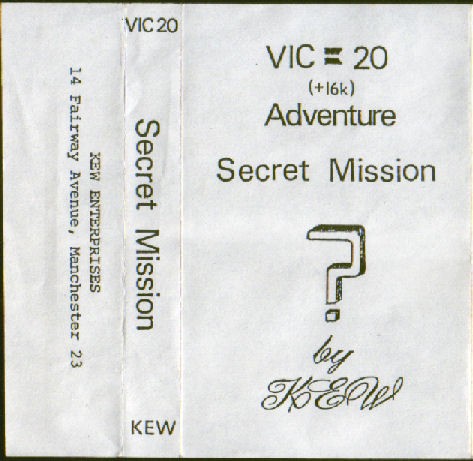

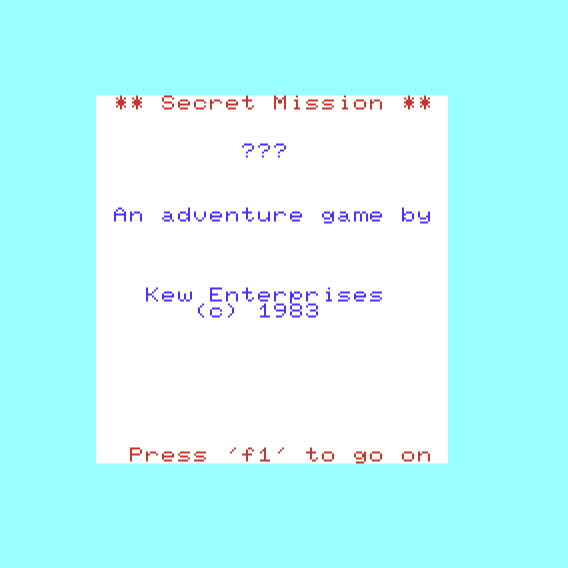

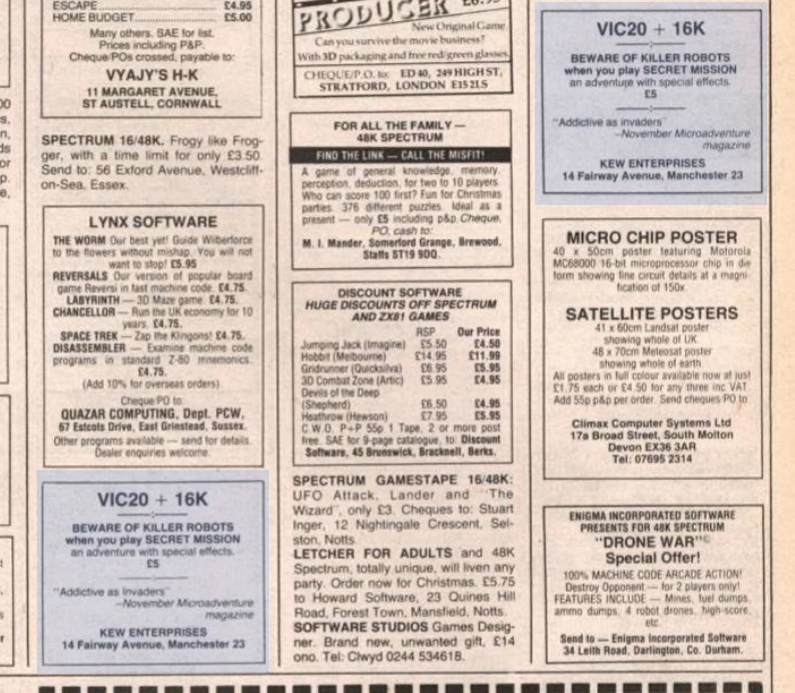

The Puzzle Pack games were eventually republished for MSX and Plus/4 under the name Can of Worms, with a few modifications, and Kew Enterprises still mentioned on the game’s screens. What’s puzzling is after this game was picked up Kew Enterprises started advertising their game Secret Mission on their own, using magazine classified ads.

I don’t think there was some kind of animosity, especially given the continuing use of the other product. It might simply be a matter of platform; Secret Mission was a VIC-20 game (for systems with a 16K expansion) and Sumlock started to focus on C64 games from this point, adopting the label LiveWire (but still “published by Sumlock”; they’re the same company).

From Everygamegoing.

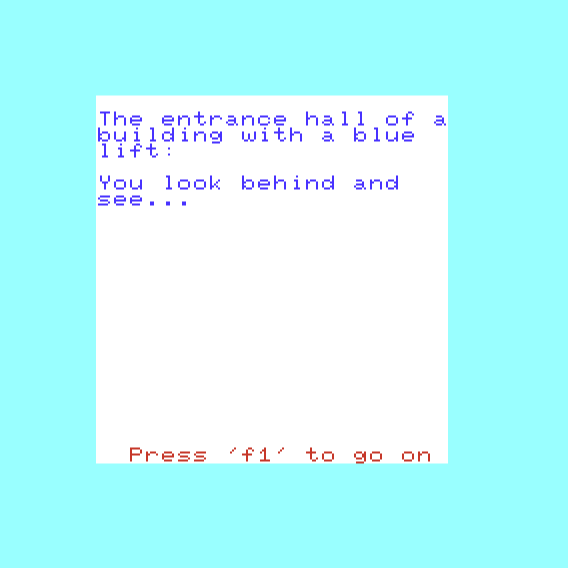

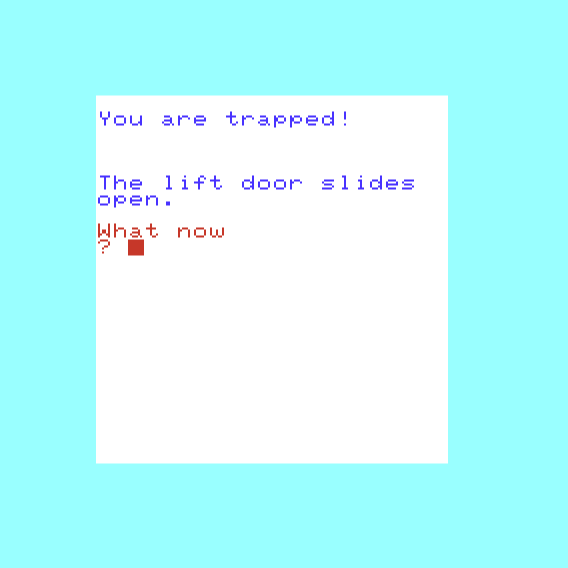

Our job is to infiltrate a building and disable a rogue computer.

This is animated.

You need to LOOK in every room in order to see items. Furthermore, for many rooms the game starts by prompting if you want to use a computer terminal while there; the terminal indicates which floor the player is on.

Sometimes the terminal produces an visual giving the side effect of the player being “hypnotically distressed”.

While I’ve finished the game, it is far more complicated than you’d expect from a VIC-20 game, so I’m saving the rest for a part 2 where I’ll do my playthrough. The game includes one of the most outrageous puzzles I’ve run across in an adventure game and it is overall convoluted enough (and obscure enough) it is possible the number of people in the past who finished are in the single digits.

Eventually one of these posts is going to start with the Big Bang, and it’ll still make sense how we get to a type-in Latimer program in the yellow pages of Family Computing

cosmic microwave background image with arrows at salient analysis points explaining the failure of Commodore to fully capitalize on the Amiga

“Behind the scenes”, incidentally, when I found out Kew’s other company affiliation, my reaction was “the calculator company!?” and that sent me down a very long rabbit hole where I had to sufficiently explain how a calculator company ended up being just a small shop in Manchester selling dodgy VIC-20 games (their C64 stuff is decent…)

I genuinely found it helpful to realize that the very first calculator did include subtraction, it waws just a particular decision in Pascal’s design to use the 9’s complement shortcut, that the physical underpinnings were exactly the same Sumlock’s calculator, that money-changing was baked into the design, that all these things put together made them on a very stodgy course even when they had the good luck of Nobert Kitz running across the Sumlock folks by chance (no way that would have otherwise been first to the post) hence they were too conservative to beat Sinclair to the pocket calculator even when they had the design ready.

Another incredible article that combines the history of an interactive fiction game along with the actual history of mathematics and astronomy along with their intellectual luminaries.

Thank you!

The Andrew Booth link doesn’t work.

fixed, thanks!

Pingback: Secret Mission: Misdirection | Renga in Blue