Howard W. Sams — previously employed for Goodyear and General Battery — eventually landed at the battery manufacturer P.R. Mallory during the 1930s (headquarters: Indianapolis, Indiana). While there his responsibilities included sales literature and he got involved with technical printing like with the Mallory Yaxley Radio Service Encyclopedia (1937).

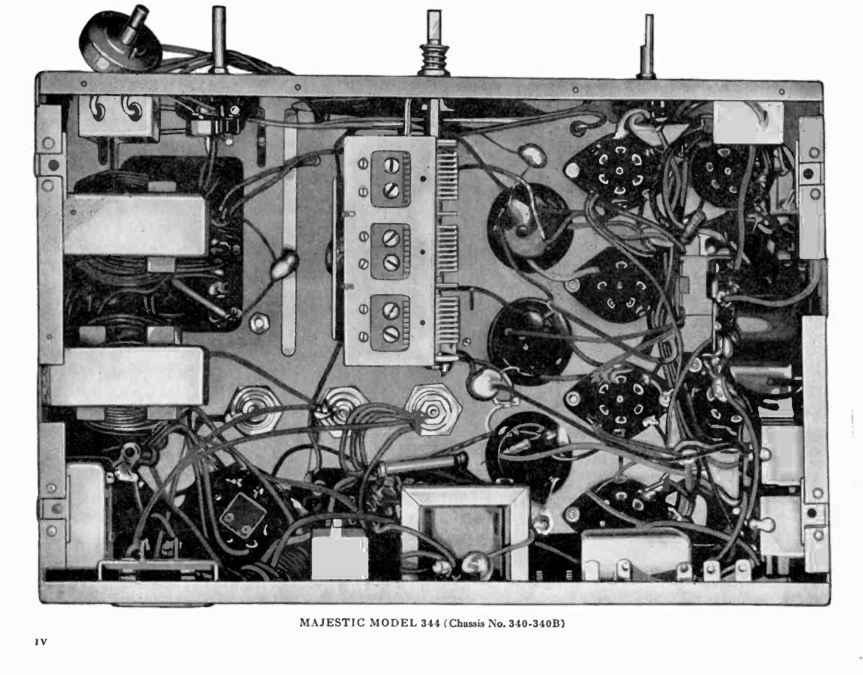

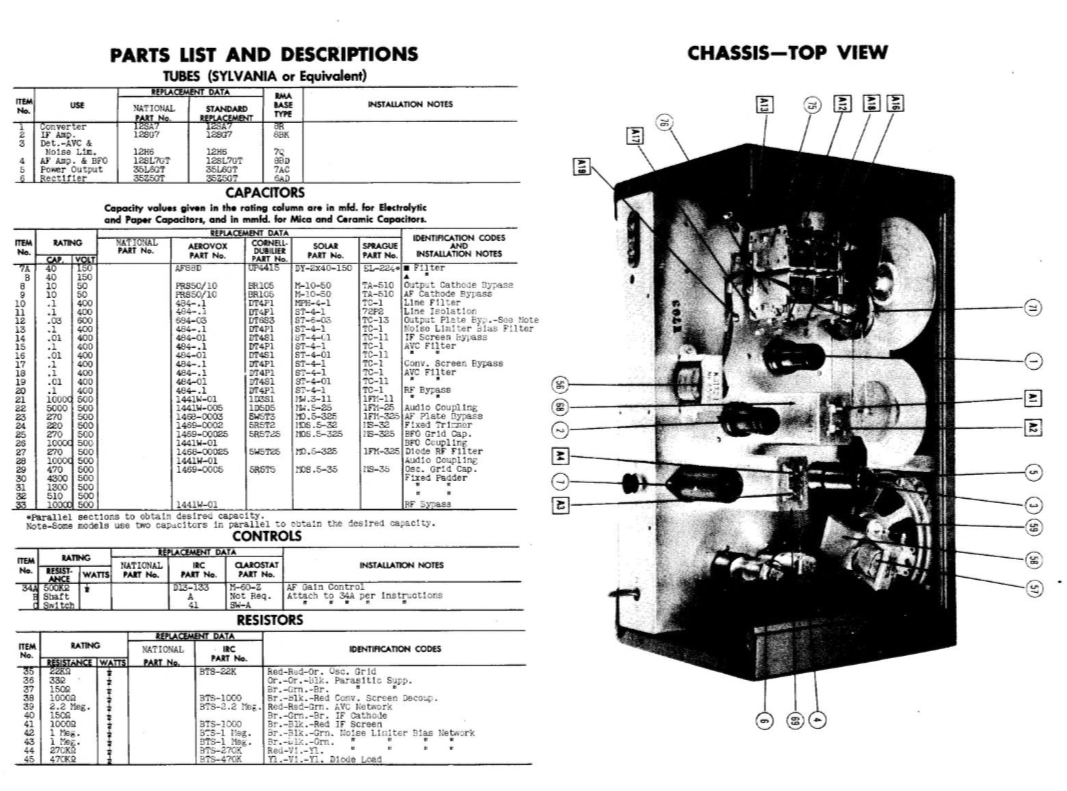

He tried to coax his employer into diversifying into technical publishing in general; being rebuffed, he founded his own company in 1946, named after himself. Howard W. Sams and Co. became prolific in publishing “Photofact” guides and their technical manuals are still valued by people who work with old electronics.

From a 1948 guide to the National NC-33 receiver.

The company Sams eventually became large enough to purchase Bobbs-Merrill Publishing (famous for The Joy of Cooking) and diversified into textbooks in general before selling the company to ITT Corporation in 1967 (while eventually being sold again in 1985 to Macmillan Publishing).

As a technical publisher, they got into computers early, like with the Computer Dictionary & Handbook (Sippl, 1966)…

…or the book Computers Self-Taught Through Experiments from the same year. The culmination, Chapter 17, is titled Building a Calculator.

You might assume they would immediately make a natural segue into programming languages when those books started to appear, but their books through the 70s tended to stay at their roots in electronics, aimed the “circuit design” layer. The first book of theirs I’ve been able to find with programming is the 1977 volume How to Program Microcomputers, followed by The Z-80 Microcomputer Handbook from 1979. Both stick solely to assembly language. In 1980 Sams finally broke into the mainstream source code market with the Mostly BASIC book series by Howard Berenbon (an automotive engineer in Michigan who worked on computers in his spare time).

Berenbon, from the second Mostly BASIC book, 1981.

I’ve referenced the first book before as it has an early CRPG, Dungeon of Danger. It is not impressive as a game, but it does represent Sams entering the software industry, in a sense. They soon after entered the software industry proper (with boxes on shelves). But why?

It could be brisk sales of the book (enough for a sequel) gave them favorable thoughts. However, my current best theory has to do with a competitor: in late 1980, the California company Programma was bought out by the Hayden Book Company. The timing is suspicious: in March 1981 Sams formed the spinoff division Advanced Operating Systems, and they hired a former Programma employee, Joe Alinsky, to be in charge of the division.

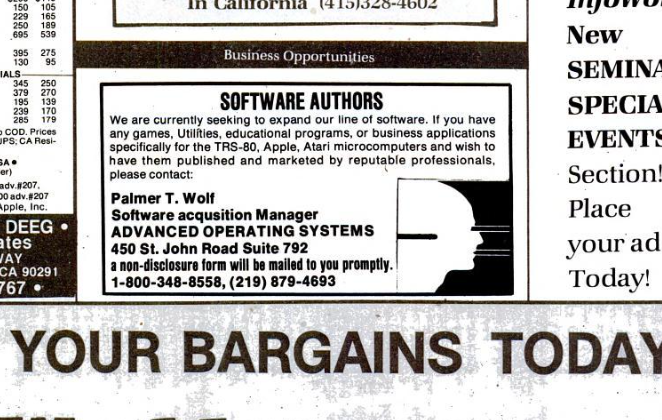

Unlike Hayden, Advanced Operating Systems planned to build their catalog from scratch. Palmer T. Wolf (previously at Instant Software) was hired as the “Software Acquisition Manager”. Wolf blitzed classified ads in the trades looking for submissions.

InfoWorld, Nov 23, 1981.

In the original 1982 printing of Caves of Olympus, he even included a letter in the manual identical to one from magazines. I haven’t been able to unearth anything about the authors (Thomas and Patrick Noone) and if they had any prior relationship with Sams, but it is possible they simply saw one of the ads and sent their game in. (Wolf claimed “50 submittals” in his first six weeks, so around one game a day.)

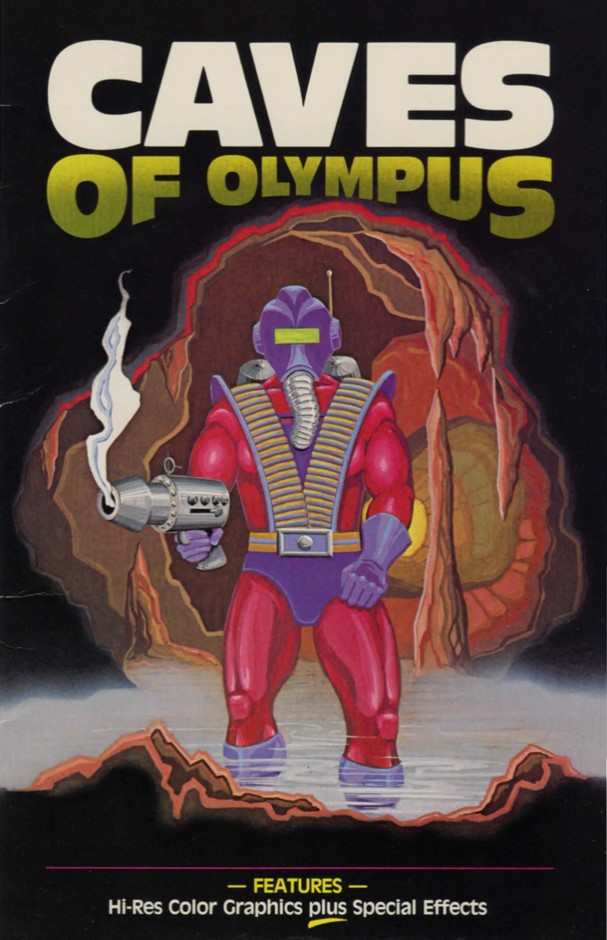

From the Museum of Computer Adventure Games.

The above is the cover from 1982. The survival of Advanced Operating Systems as a separate division from Sams was short-lived; they got wrapped back into the fold in 1983 (without Alinsky and Wolf), so a re-print in 1984 of this game is purely under the Sams label (I’ll show what that cover looks like in a later post).

This is the only adventure game published by Sams and the only game by Thomas and Patrick Noone. (The credits also list a documentation editor, Jim Rounds; shockingly, a company renowned since the 40s for providing documentation for technical devices cares about their documentation.)

On the devastated planet Olympus, beneath the ruined palace of the Emperor, lie the Caves of Olympus, the last fortress to withstand the onslaught of the evil Loren hordes.

You are Anson Argyrus, an advanced Vario-500 robot. Stranded and alone, you must make your way through the caves to safety and freedom. Cunning is your ally, reasoning is you1 weapon, as you battle against the destruction waiting at every turn-false chambers, one way doors, death traps.

But negotiate the caves successfully, and you’ll escape to join the rebel forces gathering to counter the Loren invaders.

We’re a robot! I think the last time we got close to that was Cranston Manor Adventure but that was pretending the “I am your puppet” perspective had a digital avatar in the world conveying information to us. Cyborg from Michael Berlyn united both the the player-avatar and the computer-narrator. Here, we are straight out playing a robot, no human attributes at all. Not only are we a robot, we’re a small robot “a little more than fifty centimeters tall” and who is centuries old. We are in fact old enough to have helped build the Caves of the story, but our “bio memory” has failed us so we don’t remember what’s inside.

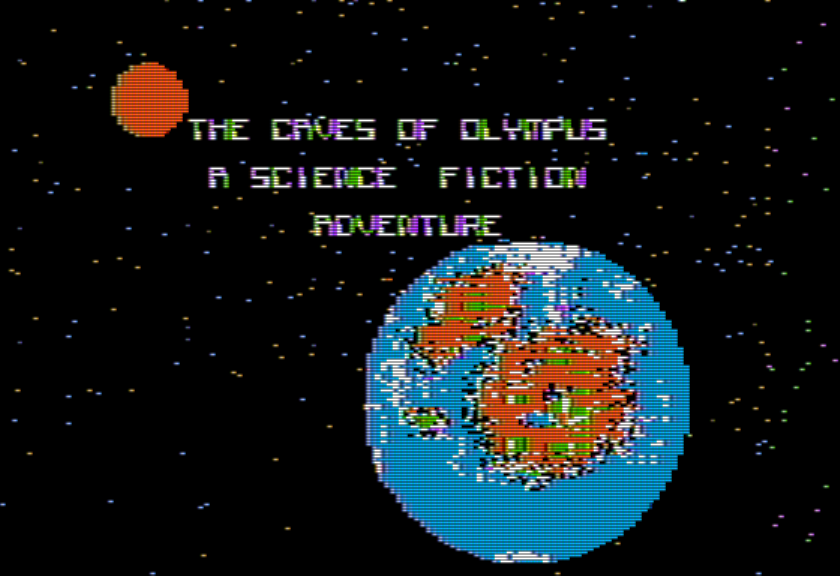

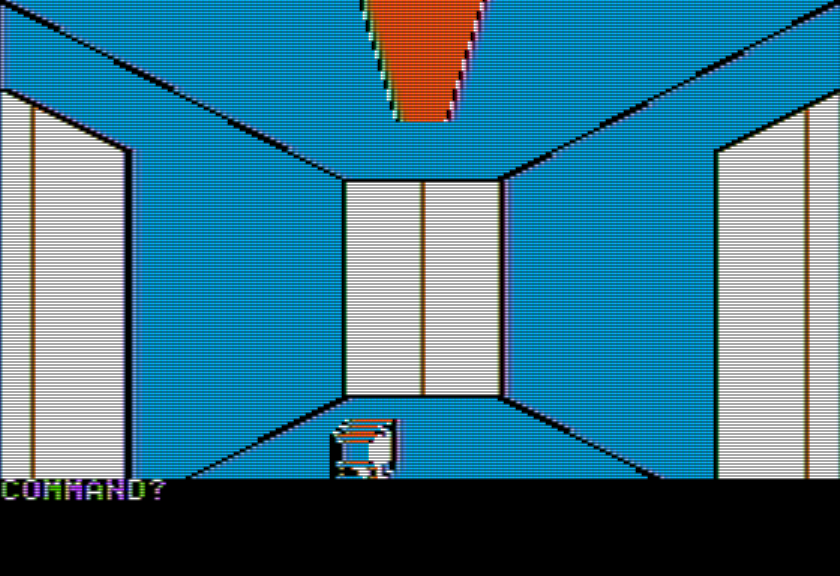

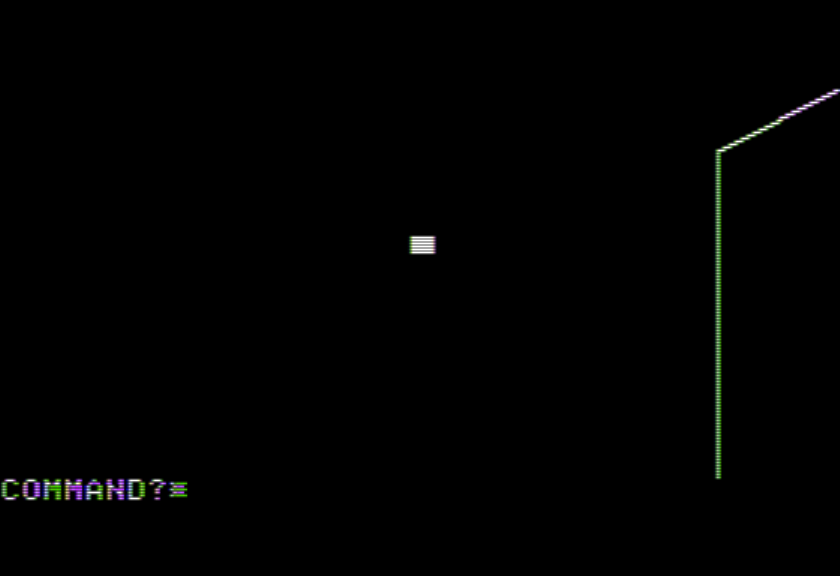

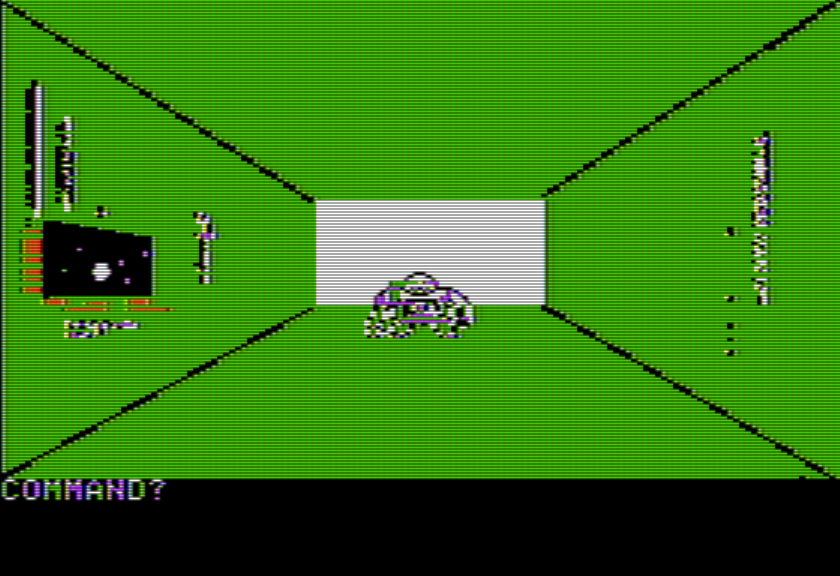

Regarding the graphics, the display uses Jyym Pearson logic where you press enter to swap between text mode and graphics mode, and you pretty much have to keep swapping between the two as you’re walking around as you don’t get enough information conveyed while in graphics mode.

I should also highlight — and it will become more obvious soon — the actual graphical style is very different than anything we’ve seen before. Essentially all the 1980-1982 Apple II games have used some form of vector graphics, like Mystery House; some have looked better, and have incorporated wavy lines and fancy fill effects and the like, but still there’s a sort of basic continuity where it is easy to recognize Apple II graphics as falling within a certain family tree.

No vectors: Caves of Olympus relies heavily on pixels. This is very different from every other adventure game I’ve played in 1982.

Notice the random break-up of mountain ridges by pixels rather than smooth curves. It’s almost like the authors added “noise” as a stylistic feature. It looks as if at least part of the images are being stored as bitmaps.

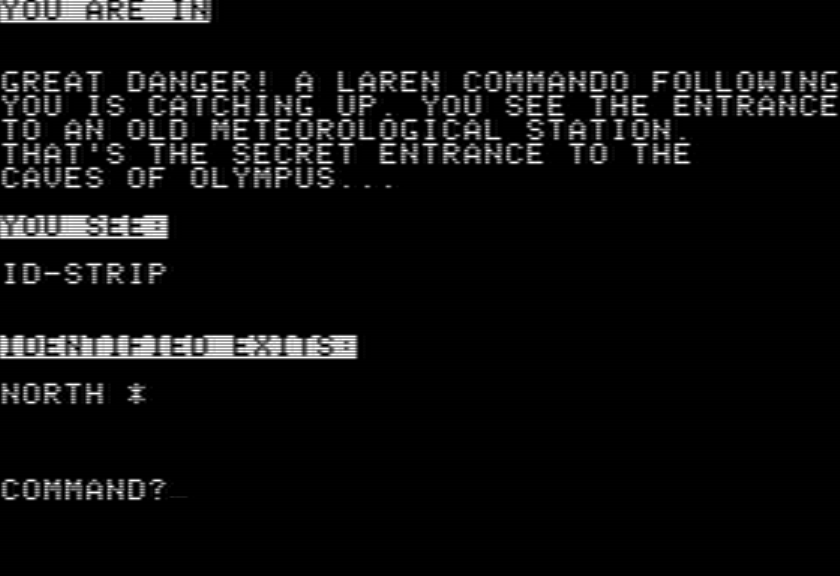

I’m not sure what to do with the ID-STRIP. Trying to TAKE, EXAMINE, etc. just gets the message RESULT: NEGATIVE! and if you waste more than one turn before going inside the meteorological station, you die. So I’m going to assume the strip works automatically for someone travelling north to keep the Bad Guys out.

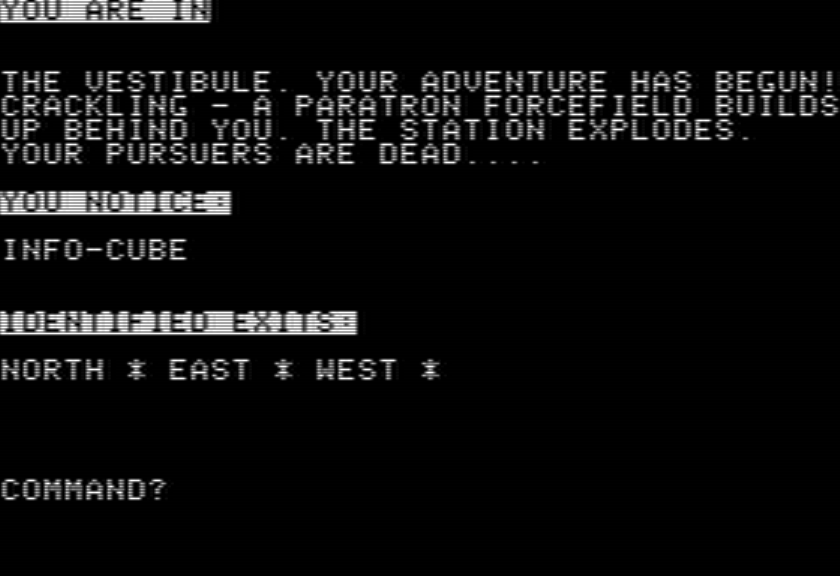

Going in, we arrive at a “vestibule”.

TAKE INFO-CUBE: “THE CUBE GLOWS IN A WARM LIGHT … WHAT INFORMATION MIGHT IT CONTAIN?”

The room description includes some “narrated action” which skips some steps. Rather than going from straight outdoors to the room we’re in, our robot hero goes from the outside to a meteorological station, and from there into the caves. The part in the middle is skipped over, more like a gamebook than a regular adventure game. Not all room descriptions are like this but there are some others which assume action rather than just description.

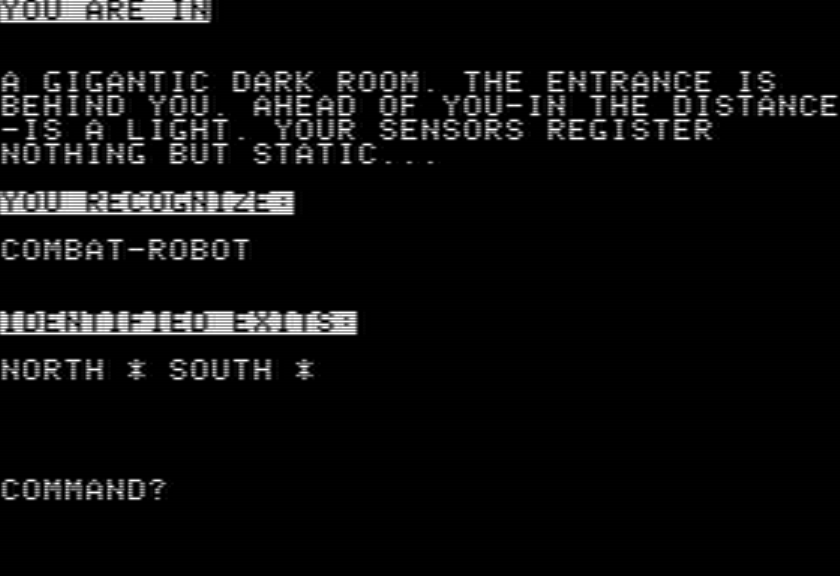

For example, heading north, there is a dark room with a combat-robot (fortunately you can just sneak on by)…

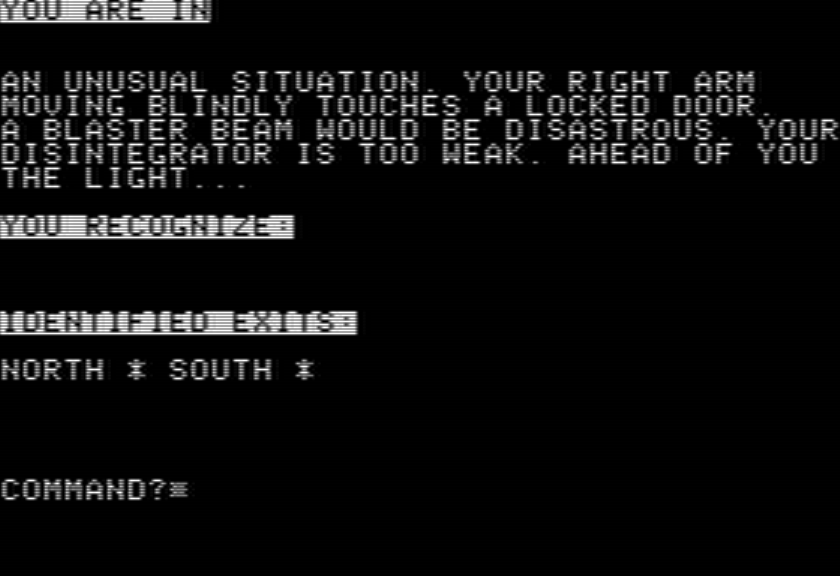

…and the room farther north is both described and depicted quite oddly.

This sort of room description tends to get avoided in modern text adventures, since it doesn’t hold up well to repeated viewings. For example, if you go back to the starting vestibule, you get the same dramatic description as if you just entered the room with the station exploding behind you.

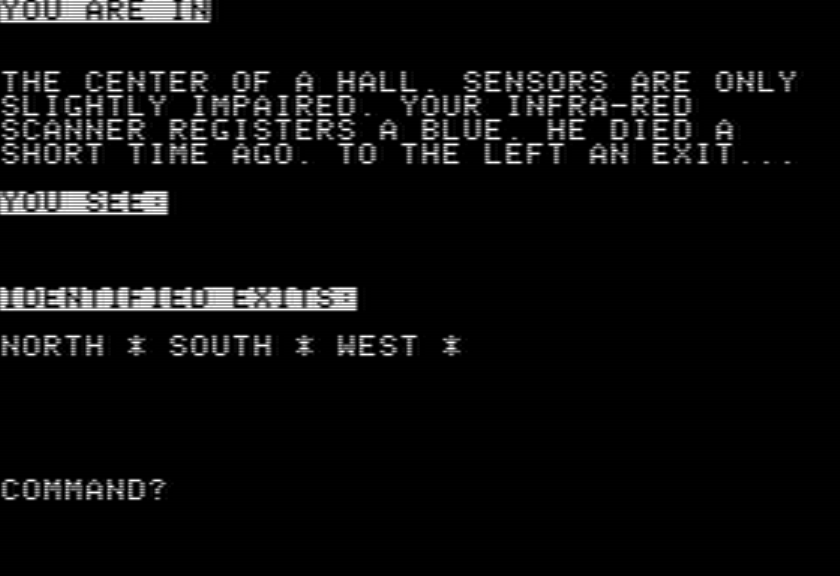

Moving on further, you reach a hall with a dead creature.

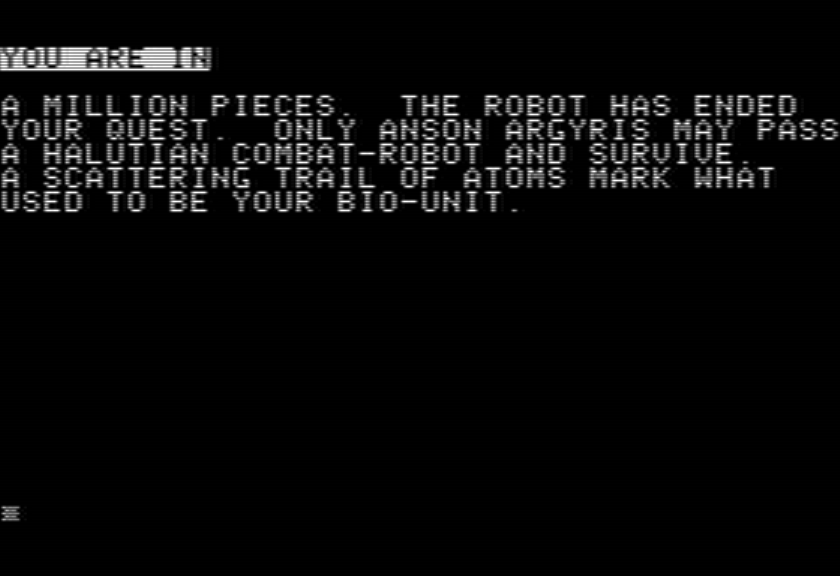

Taking a turn west, there’s a combat robot, and trying to move on further is disasterous.

I’ve explored more rooms but I’m still getting a feel for the geography (and what interactions really work) so I’ll save more details for next time.

(And thanks to Allen Wyatt, who has been helpful with the history here, as he worked for Advanced Operating Systems starting in mid-1981. He moved to Michigan City to be closer to AOS in late 1982 but had to move again a few months later to Indianapolis when the operation got wrapped back into the main headquarters location.)

I’m kind of amused by the room descriptions which play with “You are in” and follow up with a state rather than a place, like “Great danger” and “A million pieces”.

I’m always fascinated by games with deviant room descriptions.

There was one of these with room descriptions like “You’re in Trouble” and “More Suffering” and I used those on my map and y’all thought I was editorializing, but I can’t remember which one, anyone know?

I don’t know, but I’m currently suffering through the mapping of an absurdly oversized desert maze in Sharpsoft’s Mexican Adventure, and I’ve taken to naming the rooms ‘”DEEP HURTING”, in honor of the infamously endless sandstorm scene in one of those MST3K Hercules movies…

This is an interesting one– I’ve not seen it before.

With regard to the pixelated “vectors”, can you describe how the color fills? Is it the same as you would see in a typical Sierra Hi-Res adventure where the lines pre-populate and then the color paints in over about 5-6 seconds?

Also, I’m confused that you call out the misspelling of “vestible” and then the following screenshot has it spelled correctly. Was it just a one-time error?

It is absolutely nothing like Sierra. No fill. It’s a left-to-right wipe like a transition from Star Wars. I’ll drop a GIF in my next post so you can see it.

Other issue is just my typo, but since I typed the word normally later, I think I must have read the word wrong off the Apple II screen and thought the original had a typo!

I decided to take a look for myself and downloaded the ROM to play on AppleWin. I see what you mean– first of all, the “wipe” is obfuscated if you enter the room on the text screen.

Next I would think that the “wipe” effect could mean that each room is pre-rendered? I remember reading somewhere (maybe this blog) that the Sierra Hi-Res adventures, in order to save disk space, provided the Apple with instructions how to draw their images which is why you see the room images “paint in” when you enter them. (pre-rendered images took up many more byes of disk space so could allow for fewer rooms)

Will be interesting to see exactly how many rooms this ends up being, and how they compare in size to a typical (one disk) Sierra adventure of the era.

Most enjoyable. I have always dabbled in electronics starting in the 60s. Sams texts were always most useful when digging into commercial equipment. They were quite expensive. Sometimes they were available at public libraries.

The linkage to Sams makes this game significant.

Thanks, fos1

Hayden always seemed a little more flexible (more humanities textbooks, and they published Spencer’s Game Playing With Computers in the 1970s, republished one of the PCC games books in 1980) so their foray into games didn’t seem too shocking. I admit I put a lot of effort into “why would Sams go into games publishing” because their older books always seemed so serious and I always associated them with heavy lists of transistor parts. Their 80s stuff is “friendlier” but they still did Photofacts for computers.

Advanced Operating Systems is additionally kind of a hilariously stodgy name if you’re publishing games, so I wonder if they were going to focus on utilities (like Apple-Aids, which Allen Wyatt wrote) but when they brought the outsiders in (Alinsky and Wolf) they steered things differently.

The impression I get from flicking through the old magazines is that Sams decided they needed a new name to market software instead of books, and were indeed more focused on utilities in the beginning. In fact, the earliest ads for Caves of Olympus offered a contest for the first three players to solve the game, and the prizes were some cash and a bunch of their (generality quite expensive) utility programs. By early/mid ’83 they were repackaging all this stuff and selling it under the parent brand name, so this experiment didn’t last too long. They kept releasing games until just after the market crash, but I wouldn’t say they ever really emphasized them over the utilities and books.

It was interesting seeing the critical takes on this game from the era. I definitely get the impression that the graphics came across as a bit unusual, but opinion seemed split on whether they were good or bad. Almost all reviewers (except Kim Schuette) thought it was quite difficult, though. As for me, I only remember one friend of mine having it at the time, and I vaguely recall wandering around aimlessly and getting killed a lot when I played it once or twice over at his place, but otherwise it seems to have kind of fallen into a memory hole compared to many of the classic Apple II graphic adventures.

Pingback: The Caves of Olympus: [YOU ARE IN] PANIC | Renga in Blue