In the 1970s and 1980s, with each new computer system that arrived — the ones that because semi-popular, anyway — there came a blizzard of new books. Because computers were closer to the metal, a lot of these were lists of programs (typically in BASIC) although there were also programming tutorials in BASIC as well.

A sub-genre of the BASIC programming book was the one specifically for programming adventures.

From 1984, 1984, and 1985.

While there’s a little discussion of making your own game in the Captain 80 Book of Basic Adventures, that book still served mostly as a vehicle to print existing adventures. Writing BASIC Adventure Programs for the TRS-80 by Frank DaCosta is the earliest book I’ve found to be solely devoted to learning how to program adventure games.

Frank DaCosta’s first book was How to Build Your Own Robot Pet from 1979, and it honestly has an impressive goal, as the book includes: “full details on building a navigation system (Soniscan), a hearing method (Excom), a way of talking (Audigen), and an understandable language and grammar (Fredian).” You can see at this blog someone’s attempt to make the robot described from the book, which took 3 years while mostly using authentic 1979 parts.

From Ezra’s Robots, which contains much more detail about the process.

The same book has an autobiographical blurb:

A Trinity Divinity School graduate, he lives in Hollywood, FL. with wife Cheryl.

The blurb from the adventure book just describes DaCosta as a “computer hobbyist” so it seems that he was working as a pastor and doing robots and computers on the side. He still is a pastor in Texas and you can see some pictures at his blog where he writes about training pastors in Rwanda.

What I’m unsure the author is even aware of (although I have sent a message) is that the book, while only being a minor influence in the United States where it was originally published, was a major influence in a different country, nearly the starting point for all text adventure games in a particular language.

I’ll return to that story later. For now, let’s discuss the book itself. It contains two games, Basements and Beasties and Mazies and Crazies. The latter is a top down ASCII action-adventure, sort of like Kingdom of Kroz or The Thor Trilogy. Hence I will not be playing it here, but here’s a video in case you’re curious:

Basements and Beasties is instead a traditional text adventure, and the way the book is structured is to give the code piece-by-piece in a way that makes “beta versions” of the game playable as it works up to a full listing.

For example, the book starts with the map, and a “table of directions” that most adventure game designs used…

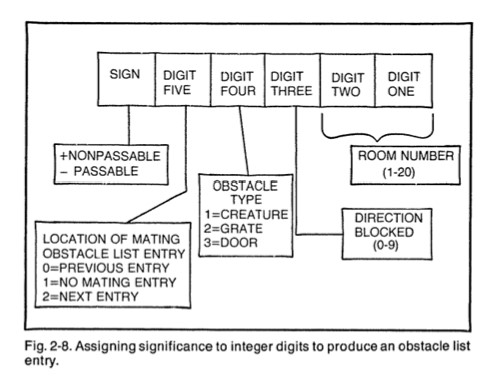

…and a relatively elaborate system for placing “obstacles”.

This section also claims “An adventure program is hardly complete without a maze.” Well, it was the 80s. (Honestly it is a little bewildering. One of my old projects from ’87 or so I didn’t keep — I was very, very, young — I included something like five or six mazes. It was just the thing to do!)

The first chunk gets summarized at the end of chapter 2:

1. A scenario is made up of rooms.

– You need a room list of short room names.

– You need a long description for each room.

– You need a room status array to indicate if a room is unvisited.

– You need a scenario map of room interrelations.

– You need a travel table defining entrances and exits.2. A scenario is made complex by obstacles.

– You need living obstacles such as creatures.

– You need inanimate obstacles such as locked doors.

– You need an obstacle list defining the obstructions.3. A scenario is occupied by objects.

– You need treasures, tools, and creatures.

– You need an object list of short object names.

– You need a long description of each object.

– You need an object status array to locate the objects.

With all the basic concepts defined, the book then starts writing actual code down.

Commands are added pieces by piece (motion, doors/items, combat, metacommands like SAVE) until a full source listing in chapter 9.

If you download the game from a site, like the version I have here at Github, it will be a reproduction of chapter 9. No typos I can find! This doesn’t sound bad, but–

The author isn’t done yet. He’s trying to follow the whole process of software production, and there’s still chapter 10, “improving the program”, full of optimization that do not make it into that source code. As is, doing one move takes about 11 seconds at authentic speeds (by comparison, Arctic Adventure from the Captain 80 book takes about 1.5 seconds).

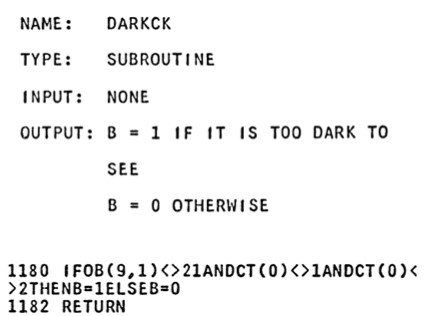

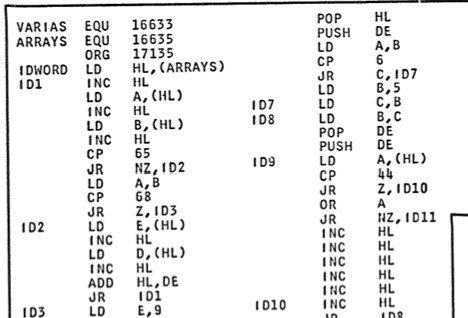

For example (as pointed out in chapter 10), when entering input, the game checks every word entered against every word listed in the word table, which is extremely slow, meaning if you feel inclined to swear at the game (perhaps inspired by French Colditz) you have to wait an agonizingly long time before the game tells you it doesn’t understand. As an alternative, the book provides actual machine code.

That … might be overkill? To compare to Arctic Adventure again, that game is solely in BASIC yet runs about 10 times as fast. The problem with Beasties seems to be that the game is not loading all its data into memory at once. That is, it makes a series of DATA lines containing verb names, object names, and so forth, and dynamically has the game pick which line of DATA to read (making convoluted use of the POKE and PEEK, commands long gone after the fall of 80s BASIC) as opposed to just having all the data get front-loaded into an array right at the start of the game. Look at one of the early lines of Arctic:

40 O = 41 : FOR A = 1 TO O : READ O$(A,1), O$(A,2), O$(A,3) : NEXT

This goes through lines written later in this format

1190 DATA Cave, 4, , Down, , , Ice brick, 0, , Trading post, 10, , Eskimo home, 10, , Eskimo, 12, , Cabinets full of supplies, 12, , Sign, 12, “The sign reads: We trade treasures for supplies.”, Polar bear, 11, , Flare gun, 11,

storing three aspects: the location, the object name, and potentially the object description. Every single object is read once and only once, then stored in the array O$ and only accessed in O$ from there on. Beasties, rather than storing all the information in an array, repeats reading DATA every time it gets used. DaCosta’s method is in a way much more clever but it has negative impact on the gameplay. On TRS-80 even on a max speed emulator a delay is noticeable enough to be painful.

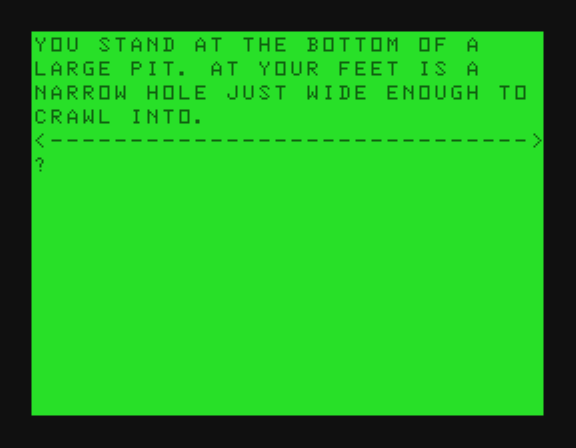

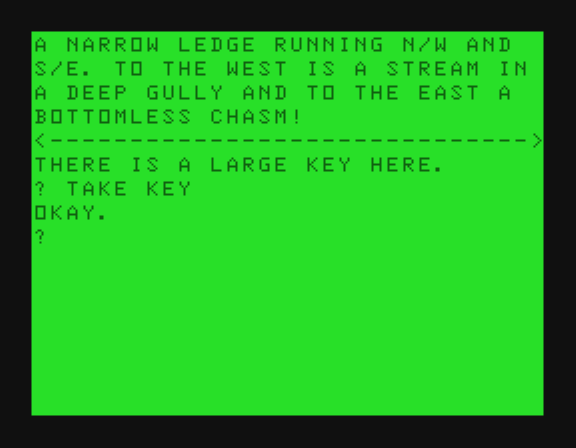

I still gave it a serious try. Here’s a preview of what’s going to happen a lot during the game.

I ended up switching over to the port by Jim Gerrie for TRS MC-10 instead.

Fine, other than the command speed, how does the game play?

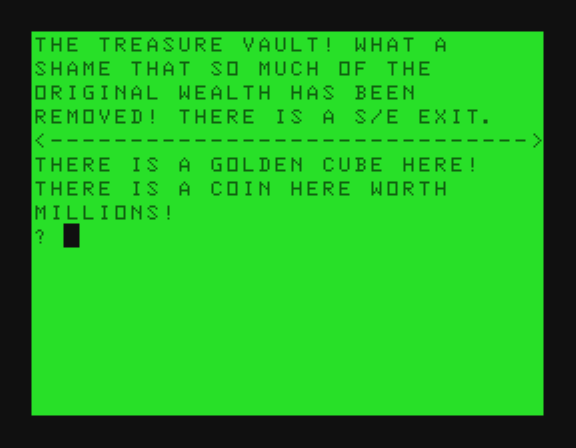

Well, it’s a little bit of the “slot machine” style. There’s not really any puzzles, unless you count finding a key and unlocking a door.

The point is simply to collect treasures and drop them in the starting room while also killing various monsters that appear. The problem is that the way combat works is:

a.) sometimes when you enter a room with a monster, you get killed outright

b.) if you don’t get killed outright, you use KILL MONSTER and may or may not hit

c.) if you miss, then the monster has a chance to kill you

On top of all that, there’s a wandering orc that can kill you in any room at any time, and he doesn’t seem to stay dead after you kill him.

I was not able to kill the spider with my axe but had to use a nearby “enchanted grenade” instead.

Once dying you have all your items drop where you died and you get sent back to the start (so you can rescue your items like an old school RPG). If you’ve unlocked any doors or deposited any treasures they stay, so getting to the end of the game is a matter of persistence and grumbling every time an orc appears and arbitrarily kills you again.

I don’t think we’ve had a Coke cameo since Crystal Cave.

There’s also no “ending screen”, you can just check your score and watch it go up, and there’s no acknowledgement if it is at maximum or not.

It’s not worth fussing that much over the gameplay, because this is a tutorial-programming game, like Planet Pincus; the simplicity is the point. While I haven’t seen evidence the book had influence in the US (it looks like nobody bothered to upgrade the parser and there were other sources by 1982 of text adventure templates to use) it apparently hit big in Hungary.

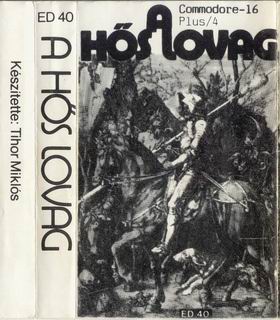

There were three Hungarian-language text adventures in 1985, but where the penchant for writing adventures really started in Hungary (according to the Rosetta Interactive Fiction blog) was 1986 with the publication of F. Dacosta’s book A kalandprogram írásának rejtelmei. (What “F.” stood for was a source of speculation for Hungarians.)

I am still unclear how the book ended up making it over the Iron Curtain, but (according to the aforementioned blog) its appearance coincided with a “népmozgalommá” (people’s movement) in creating adventure games.

Some early Hungarian games directly used English sentence structure, which comes off as completely wrong in Hungarian. From the instructions for A hős lovag, one of Hungary’s first commercial games, it explains the player should type not EAT THE BREAD but (the Hungarian equivalent of) HE EAT BREAD. This is a format only used for people learning the language; the computer should be treated as if it, too, was a language learner. The instructions opine that perhaps in time the computer will recognize suffixes and learn to speak correct Hungarian.

Fascinating history! Structuring the book as a series of refinements seems like a smart teaching tool.

I hope by now we’ve finally taught the computers to speak Hungarian.

I’m under the impression that by the time the Hungarians managed to make their own adventures they had most of it under control. Most of it, because like French you have the accented characters which are vital. I do know that by the early ’90s they had it done beautifully…at which point they switched over to using English for the most part, even for native productions. (for example, Perihelion and Amberstar)

Caveat, I am not a speaker of Hungarian, but I did know a guy who did and I have a rough understanding of how the language works even if I don’t actually know how to say much, if anything in the language.

And… what’s the point of reading the DATA’s again and again? Avoid spending memory? I don’t understand.

Nice archeology work!!

Seems to be a space-saving measure, yes.

I thought I was a pretty talented programmer when I was in high school. Then, when I revisited my Arctic Adventure code a couple of years ago, I wasn’t sure. Thank you for giving me new reason to be at least modestly impressed with how I wrote an adventure game that was decently fast given that it was in BASIC.

Pingback: The Werewolf Howls at Dawn, The Case of the Pig-Headed Diamond, The Labyrinth of the Minotaur (1982) | Renga in Blue

Pingback: Mad Martha (1982) | Renga in Blue