Recently I played a game by John Olson of Kansas (as opposed to John Olsen of Oregon), Island Adventure. Purely by random chance another Olson game came up next on my list, except I was somewhat baffled at first because my brain interpreted it as Oregon John; that is, I was expecting a game with complex coding, interlocking puzzles, high enough difficulty to give trouble, and a scenario where every item is important. No, this is instead Kansas John, the one with simple coding, lots of items that don’t mean or do anything, and some of the most straightforward adventuring I’ve played.

Honestly, in its original context, it isn’t bad: it was published in Chromasette, sister publication to CLOAD. CLOAD was for the TRS-80, Chromasette for Tandy’s follow-up, the Color Computer. (I’ll get back to what I mean about context later.)

Chromasette tapes are the blue stacks to the right. From Z-JunkEmporium.

It also — despite being founded by the same person who had been editor-in-chief of CLOAD since 1980, David Lagerquist — is a lot rarer than CLOAD, and the picture above is the only one I’ve found of any genuine physical Chromasette tapes. The issue at question here is January 1981, which includes an animated line movement demo as the “cover art”.

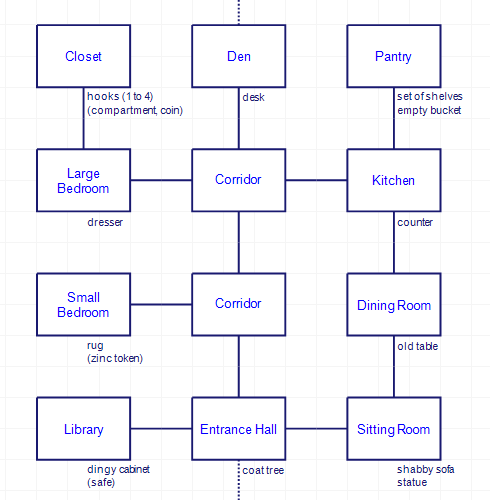

The premise lands you in a mansion where you need to retrieve a diamond.

You start with a pry bar and need to bust your way in.

Inside there are lots of shabby furnishings which have various hidden items, and really the big task is trying to nudge anything at all loose.

The coat tree hides nothing.

The main challenge is the verbs being picky.

For example, to get the hidden item out of the rug at the Small Bedroom, you can’t just LOOK at it, or MOVE it, you have to completely TAKE it. To be fair, this gets you a zinc token which might be a bit small to see just by moving.

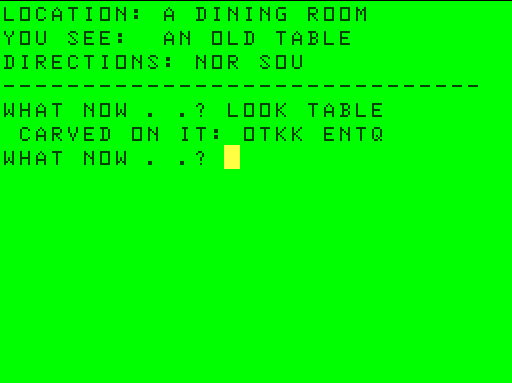

A table gives a cryptic hint: OTKK ENTQ.

The letters just shift one ahead to be PULL FOUR. There’s a closet with four hooks and PULL FOUR reveals a secret compartment with an aluminum coin.

A third artifact, a medallion, is hidden in a cheap statue.

The initial instructions mention BREAK STATUE. I always love it when instructions give a completely explicit hint about an action in the game.

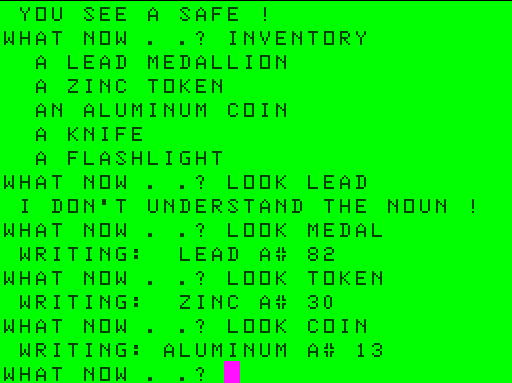

There’s a safe you can find by moving a cabinet, and the three things I mentioned (coin, medallion, token) give “atomic numbers” that can be used to open the safe.

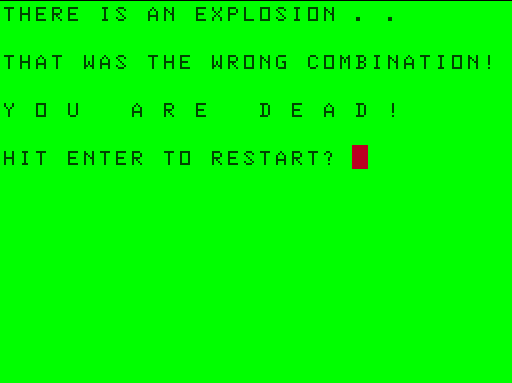

There is, as far as I can find, no hint as to what order to put the numbers in. Normally trying all six combos would be no sweat, but entering the wrong combination kills you. I got it right on the fifth try (13/82/30).

The items are a key and a notebook; the notebook gives you the hint to KSED KCIK (read backwards).

Winning then is a matter of making sure you don’t pull levers or push buttons.

For example, a tempting red button floods the passage you’re in.

There’s another trap when you reach the diamond.

Going through with the action above without using the key first drops you in a trapdoor. You need to insert the key and then the diamond is safe to take, and that’s it! There’s no more twists.

So back to context: this was a single game tossed on a monthly collection, and as such, despite it being a 10-15 minute game at most, didn’t “feel” like a rip-off. Despite a gaggle of useless objects like a flashlight and a nail file the extra parts had some comedy mixed in came off as intentional rather than bad choices.

The bucket does nothing either. In a walkthrough all you need is the key, since the code to the safe doesn’t change.

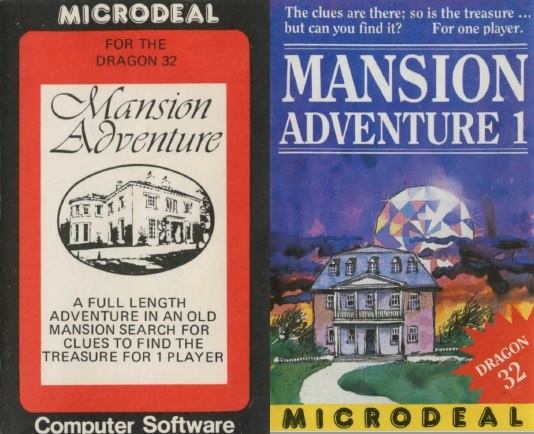

However, this wasn’t the only format the game was published in! It was published by the UK company Microdeal more than once.

We’ll see Microdeal again as this was the first in a series; I’ll get more into their history on a revisit.

So this was fun enough for a short game, but I’m not sure how I’d feel if I bought it standalone expecting a serious experience. Fortunately, I got a reaction from someone writing in the 80s so I can clock how one person felt:

Microdeal have inevitably produced a series of adventures for the Dragon, including Escape, Flipper, and Mansion Adventure, or at least they call them adventure games, Personally the only one I thought was of lasting interest was the Mansion Adventure, but then we all have our different tastes.

— Exploring Adventures on the Dragon, Peter Gerrard, published June 1984

This honestly seems inscrutable to me — the game was enjoyable enough for what it was but “lasting interest”? On the other hand, in addition to the multiple Microdeal versions there was a Plus 4 port and an (unofficial) VIC-20 port and in modern times it has been ported twice more (once by Barry Hart, once by Jim Gerrie) so maybe the utter simplicity is the appeal.

A mouse and a spider sometimes appear. They’re just for scenery.

Addendum: IF you chip away the deathtraps and dealing with finding the right search-verb, there are really three puzzles: the OTKK ENTQ code, entering the atomic codes, and the KSED KCIK puzzle. This makes it essentially a proto-version of the style of adventure with no object manipulations of note but more a focus on self-contained puzzles (like The Daedalus Encounter or Safecracker: The Ultimate Puzzle Adventure). This does make the game of note in the innovation category and is perhaps why Mr. Gerrard indicated “lasting interest” in his brief review.

Coming up next: one more game that is straightforward and simple but for very different reasons than Mansion Adventure, followed by an ambitious Apple II game that wants you to die.

The safe code is in alphabetical order of the elements (Aluminium, Lead, Zinc). So there is some pattern to it…

Likely what the author had in mind!

I haven’t found any clues that indicate that though (like NOTE: ALPHA ORDER) but I might be missing something.

If anyone wants to check the game is really easy to play online.

It’s also in alphabetical order of the items for what that’s worth (COIN, MEDAL, TOKEN).

Interesting simplicity. I understand this because of being a type-in game, but as you I’m surprised it made its way to a full-published title.

I never got a price confirmation but perhaps it was a “budget title” in the UK, one of the ones selling for only 2 pounds.

But I’m pretty sure there were three printings, so it likely only hit that on one of the later ones!

The UK market was just weird though. Microdeal’s biggest “series” and mascot from the time was Cuthbert, who looks like this. It’s like the MAD Magazine mascot got a series.

For me in the 80s my context would have shifted from “that was cool, what else is on the disk” to “huh, that was it?”

IIRC, they started off in the region of £8, which was fairly expensive for the UK tape-based market. By the end of the Dragon’s lifetime they were being sold by discounters for about £1 a pop.

(Microdeal also did C16 and Enterprise versions of some of these games too. I think those launched under the £4 mark… For comparison, £1.99 to £2.99 became the later standard for a “budget adventure”.)

eeeek 8 pounds does seem a bit much

Just based on your own memories of the past, any guess what your reaction would be?

I didn’t start buying games until Infocom was fairly well-established and that was the standard I expected from a full-price game, so I might be calibrated a bit off.

To be fair though, that £8 price appears even in a 1984 Micro Adventurer pricelist where there is quite a range of different price points on offer. For example, you have The Hobbit (with the book I think) for £14.95, the Mysterious Adventures for £10.06, Pimania is £10, Philosopher’s Quest is £9.95, the Level 9 games for £9.90, Abersoft’s version of Colossal Cave is £6.95, as is Artic’s Planet of Death. I often find, talking to other UK gamers from back then, that we’re coloured by the later influx of incredibly popular £1.99 and £2.99 budget titles sold in newsagents, and forget that prior to that games could actually be quite pricey.

I also think (although I haven’t researched the later years as much obviously) there’s a serious difference between buying in ’82 and buying in ’85, at least from the pricings I’ve seen. It’s almost like the UK had their own “crash” with a dump of budget software but it didn’t affect the market in the same way as it did in the US (which had $39 games going down to $3 because the sellers were stuck with a glut of stock; it wasn’t because the games were bad so much as they had too many of them)

lots of people remember the $3 times as “good” for the consumer because they could get lots of games but it was making Atari bankrupt in the process

the UK market never went to the same scale and even Elite sold “only” 100,000 units rather than in the millions

We didn’t have the videogame crash here but I think after a messy start, with prices all over the place, the market eventually settled to an accepted level with a place for both budget (£1.99 – £3.99) and full price titles (£7.99 – £12.99). A full price release would often get a second lease of life re-released as either as a budget title or in a compilation of multiple games.

Retro Man Cave’s video here gives a nice flavour of what you’d see when you walked into a 1980s UK computer store… or newsagents… or pharmacy! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MyYbVl3sol8

For a moment I thought the editor’s note was the blurb for the game, and that you would be roaming through your mansion looking for food–which could be anything from a trivial My House game to Curses.

Pingback: Eno (1982) | Renga in Blue