I’ve made good progress on the game. The way it has gone almost feels like the opposite of what a modern player would want to experience, yet there are aspects of the style that allow unique choices that are tough to replicate without that roughness. It’s easier to just explain in context —

A Dick Smith System 80, from Classic Computers New Zealand. This was a very popular clone of the TRS-80 in the Australasia region and there is a decent probability Doomsday Mission was developed on one. It was sold as a Video Genie in the UK, a PMC-80 in the US, and a TRZ-80 in South Africa. The clone originated from Hong Kong via EACA International Limited.

— so continuing directly from last time, I had found an elevator with a strange message. In a literal-world sense this would be a gag, but it occurred to me not long after hitting “Publish” on my last post that it might be a clue of some sort.

I tried LOOK UP which revealed a secret panel. After finding the panel you can SLIDE PANEL revealing a hole, then GO HOLE to get to the top of the elevator. There’s a cable you can then climb to make it to the second floor.

This results in a second floor chock full of more ways to die.

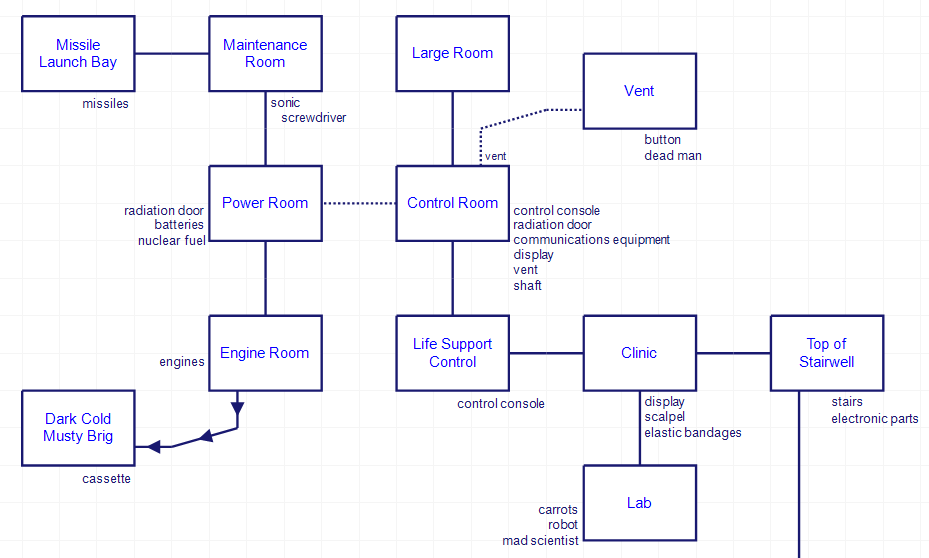

Heading south a bit leads to a Clinic with a scalpel and some badges; adjacent is a Lab with a mad scientist.

The route to avoiding death here involves a vent by the elevator. You can find a dead body of a crewmember holding a phaser held tight via RIGORMORTIS.

This moment is effective due to the opening of the game. The very first step kills you with gas. Since dropping the starting phaser to avoid the gas is not intuitive, most players (myself included) will have experienced an army of clones being killed over and over before finally getting through. Even though none of them are part of the “diegetic text” of the plot — that is, the “real”, “final” plot where we succeed — they still have an effect of the player. (See also: Pyramid of Doom.) The ghost clones gave me a fairly nervous reaction upon seeing the phaser, rather emphasized via the method of obtaining it, via sharp implement:

You can’t shoot the scientist, but the phaser works even if you aren’t shooting it.

The carrots let you see better so that when you go down stairs to the first floor (skipping the elevator) you can see the way up again. The robot has two slots for cassettes which I haven’t used yet.

Having a kick opening with dying the exact same way over and over is not really polite even in a modern time-loop game, so the dramatic effect was uniquely historical. I also like that in its most refined form, this is just a “take object X and bring it to person Y” puzzle, but the extra plot elements indicate depth beyond a node on a puzzle flow chart.

Moving on to more forms of death, past the radiation door:

The radiation can be taken care of by swiping the space suit from the first floor, which doubles as radiation protection.

More hazards still await. In addition to a PHASER the game starts you with INSTRUCTIONS that ARE PLANS TO DISARM THE MISSILES ON THIS STATION. Well, here’s the missiles, so let’s try it:

Just having an alleged shutdown button there would have just been a trap, but by having the instructions tossed in the player’s inventory from the beginning, throwing a psychological shadow, the trap became delicious. The final method of death is from dropping into a cell, the same one you see after using violence:

This isn’t necessarily a loss here but I haven’t figure out yet how to get out. The obvious choice of sonic screwdriver (Dr. Who’s chosen open-all-doors implement) doesn’t seem to work, although I may just be using the wrong verb. You can use violence to get a security robot to come by but they just eat the key to the door and otherwise ignore you (you don’t immediately die at least).

The radiation area also has batteries. After enough time the life support shuts off and the lights go down. You can insert the batteries in a torch from the first level (that’s torch = flashlight, this is an Aussie game) for the light, and for the life support, you need to be wearing a space suit when the drama hits and there’s a lever in a LIFE SUPPORT CONTROL room that resets things so you don’t need a suit on.

I assume there will be some logical reason we can’t just keep a suit on the rest of the game.

So to summarize what I’m up on:

1.) the missiles are booby trapped and may just not be disarmable at all; there might be a way through the booby trap

2.) escaping the cell (which might be easy?)

3.) surviving going through the airlock on the first floor

Regarding the airlock, I did find the BANDAGES could tie to the HOOK, but I was unable to translate that into using them as a safety net or the like. This may simply be again a matter of finding the right verb.

I do have the suspicion I close enough to the end to be able to wrap up in one post, although I also suspect I will have at least a few more ignominious deaths along the way.

I think very few players would find the missile-shutdown booby-trap death to be “delicious”. Far more likely they’d ragequit and never pick up the game again. I know I would.

That sort of puzzle embodies the often wanton, gleeful cruelty of vintage puzzle design that was clearly unfair even in the 1980s. That approach has been, rightfully, largely consigned to history, and this game is a perfect illustration as to why.

>almost feels like the opposite of what a modern player would want to experience

ayep.

I’m just hoping the historical context gets through. I wouldn’t make other people play it!

I think a good analogy would be games that have participatory comedy (which don’t just show a gag, but have the player do an action which becomes part of the gag). This is a participatory plot twist.

I really don’t think we should give the game that much credit. It’s just gratuitous cruelty of the sort that frustrated players even back then, so I don’t think there’s really anything to praise about it.

I sort of felt both ways about it. Probably I personally would have ragequit; but as an artifact to examine, I admit there also some “daaaamn that was a clever trick”.

I suffer so you don’t have to!

(and make copious save games / save states)

I feel like that sort of thing depends on how good and/or annoying the game has been up until that point. An otherwise mundane game pulling this doesn’t strike me as awful, but frankly I would relish that over another overwrought plot twist, at least with a gameplay twist there’s a chance it might be a little more interesting than something like the butler doing it.

Although admittedly, at this point I reserve my ire for adventure games that are tedious over ones that are cruel. Something like this feels like a few steps above something like Return of the Phantom or The Kristal.

The other wrinkle to this which I’ve been trying to get across is not necessarily good/bad, but just that something is providing a unique aspect to gameplay. I think the best comparison would be the two versions of Cranston Manor. The original text version had very twisty, maze-like town section which took me hours to map out. The Sierra version had the town simplified and could be rushed through in about 5 minutes. The end result was I got a strong feel in text Cranston of the town as an abandoned place, which had knock-on story effects, whereas in the Sierra version the town essentially had no plot aspect whatsoever.

I would never endorse making weird maps like the Cranston Manor map. But I recognize it ended up serving a story purpose, and it takes some work to come up with a substitute that people in 1981/1982 didn’t necessarily have.

So when authors are presenting this kind of puzzles, it isn’t necessarily because they don’t know better or they’re trying to sell more hint books! Sometimes it serves a genuine design purpose. That doesn’t mean the purpose doesn’t get swallowed up by the bad, but it does mean any game design decision is a trade-off, rather than a simplistic “it should be done this way” type decision.