Archive for February 2020

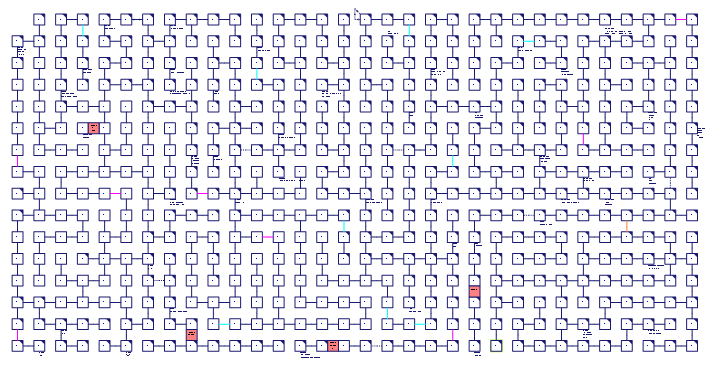

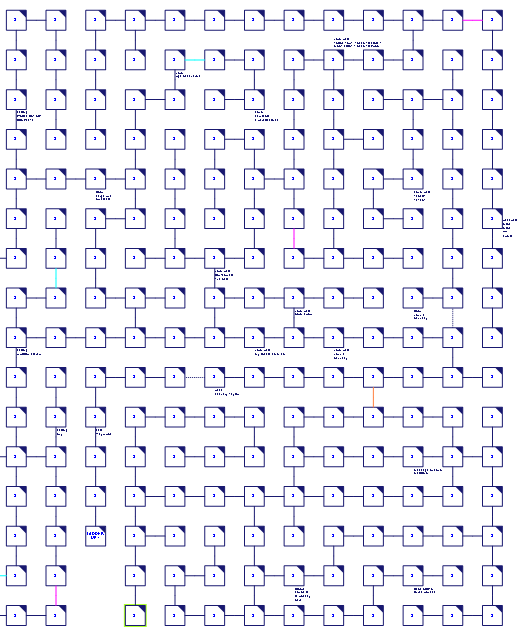

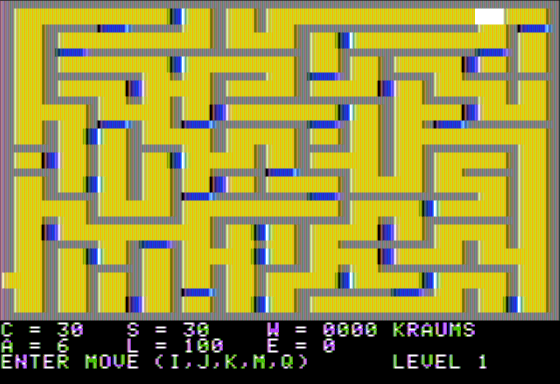

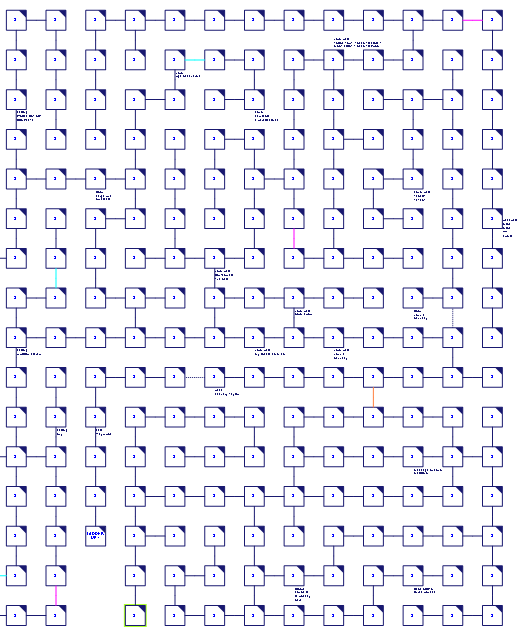

I have filled in most of the map, although I haven’t thoroughly checked everything yet.

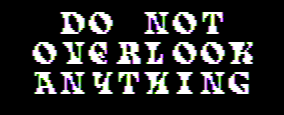

You might notice there’s the missing room in the upper left. I haven’t figured out what’s going on there yet. There is one clue right on the wall next to it

which may have been intentionally placed; perhaps there’s some obscure navigation trick I need to get into that spot.

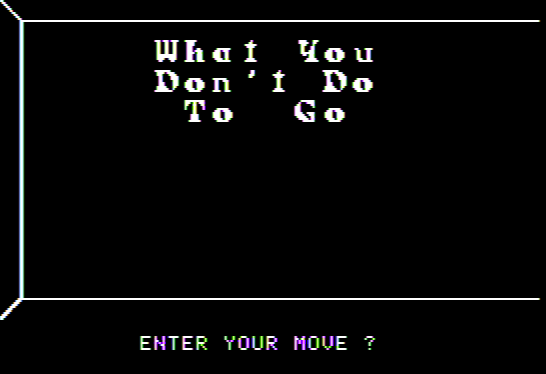

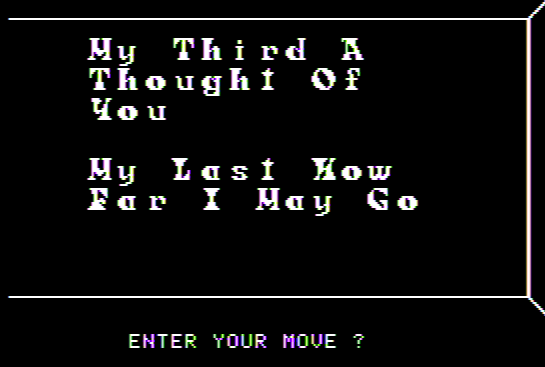

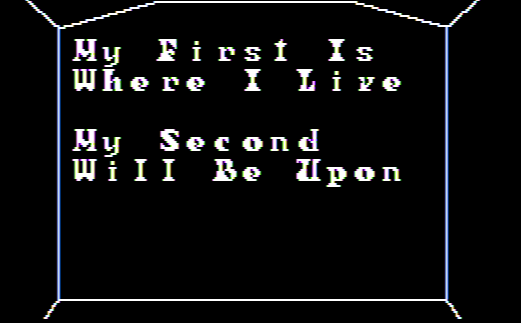

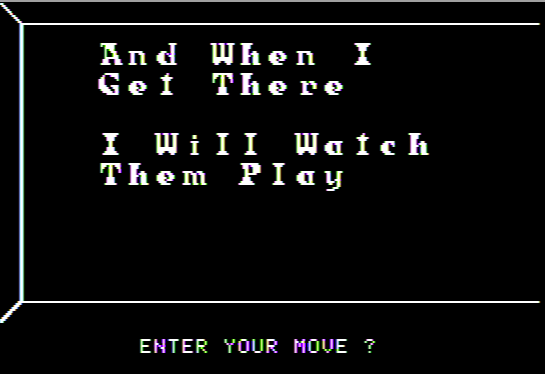

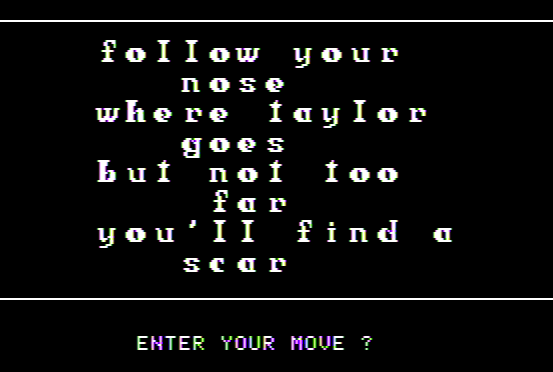

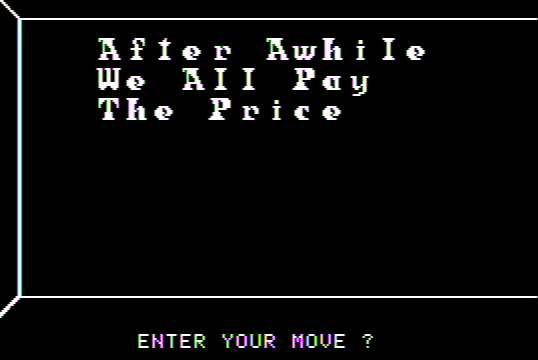

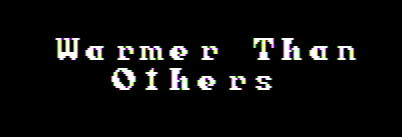

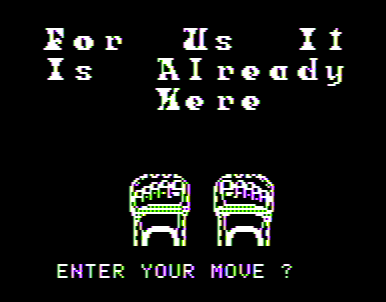

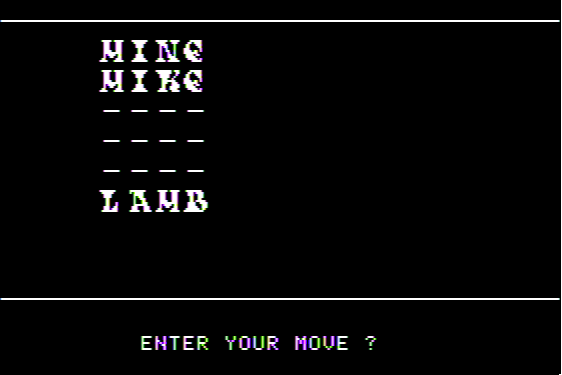

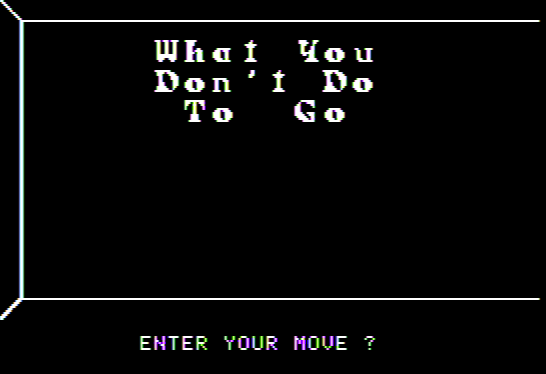

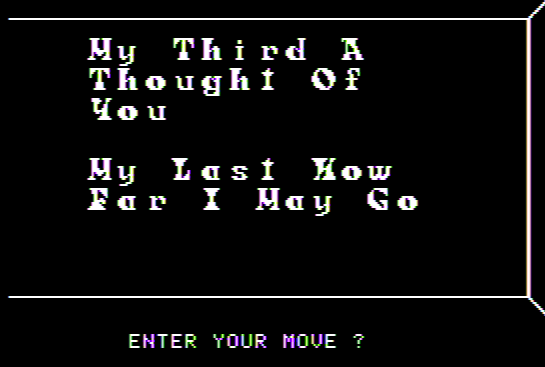

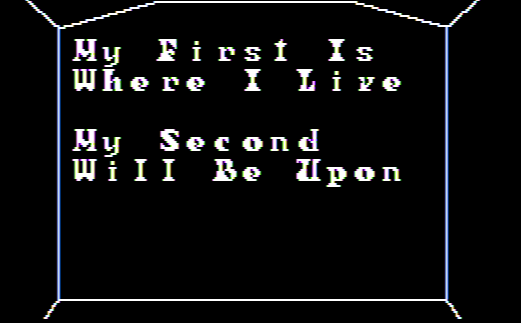

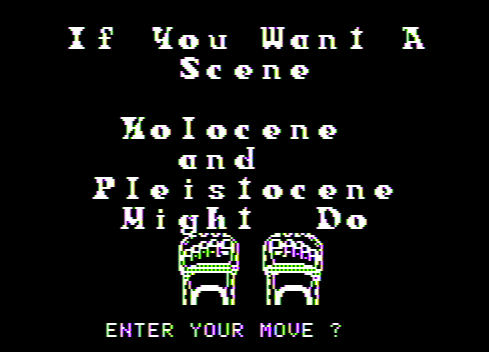

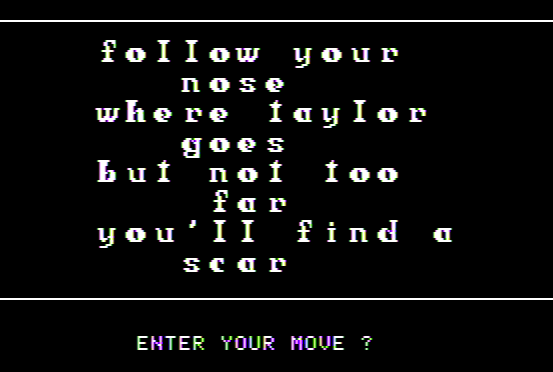

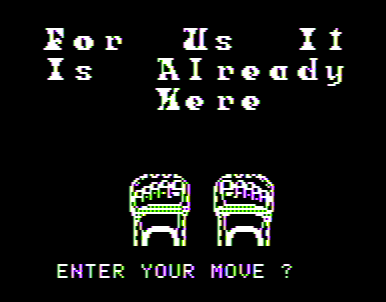

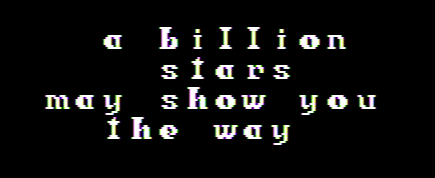

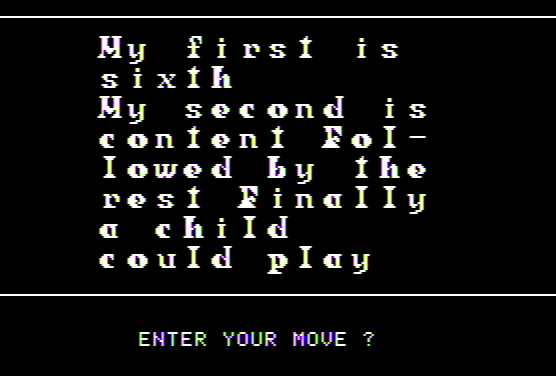

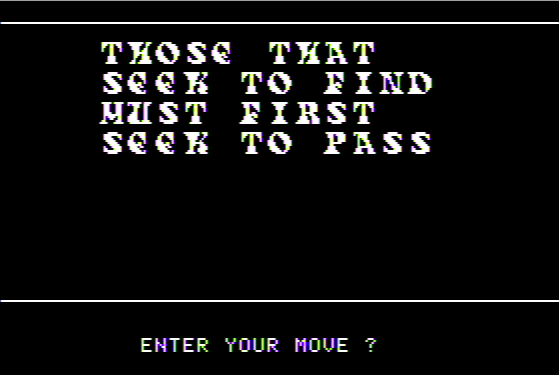

There definitely is some intentionality to the clue-placing — maybe not a lot, but some — because one dead-end had three messages that clearly linked together.

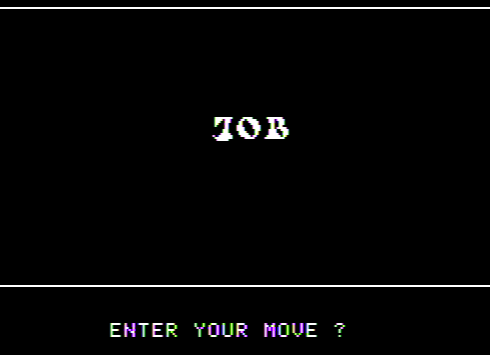

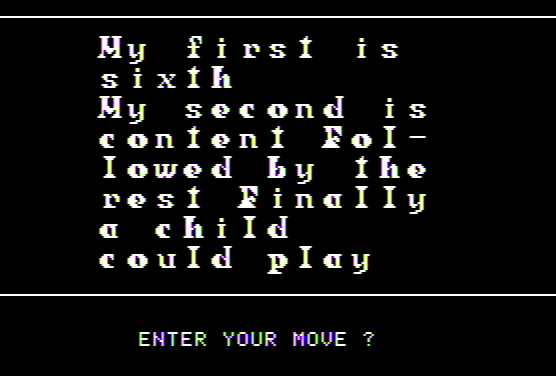

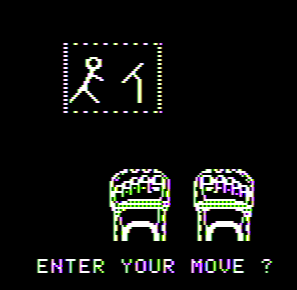

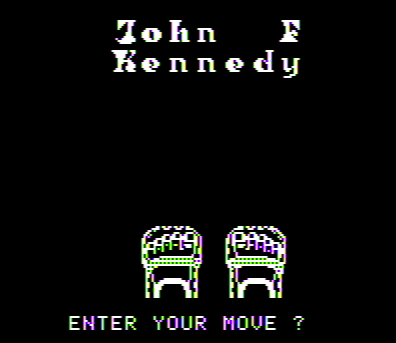

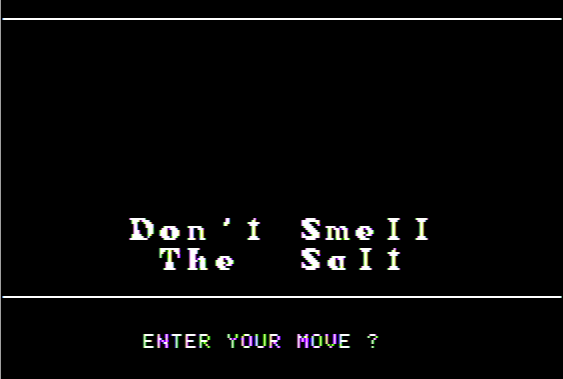

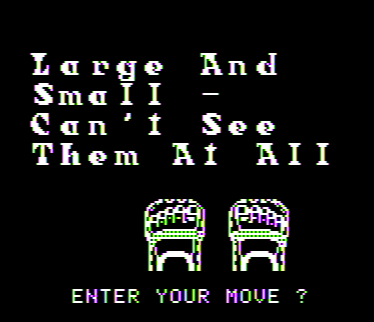

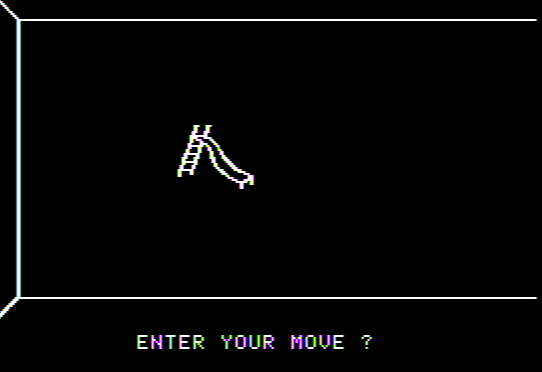

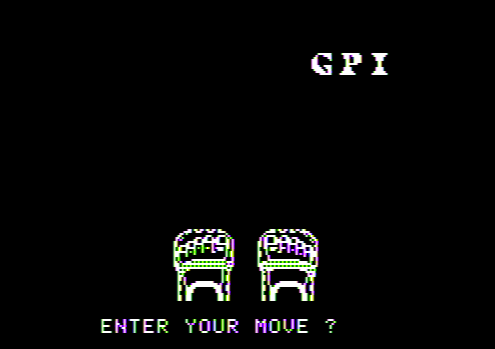

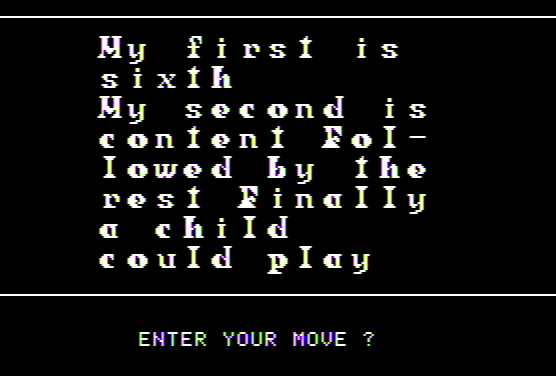

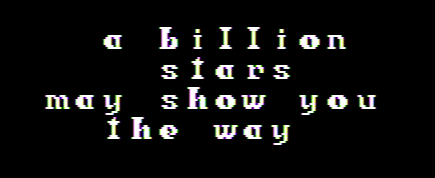

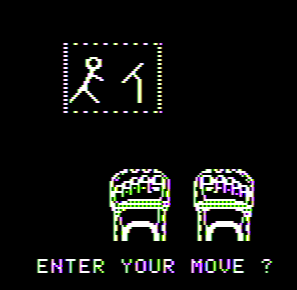

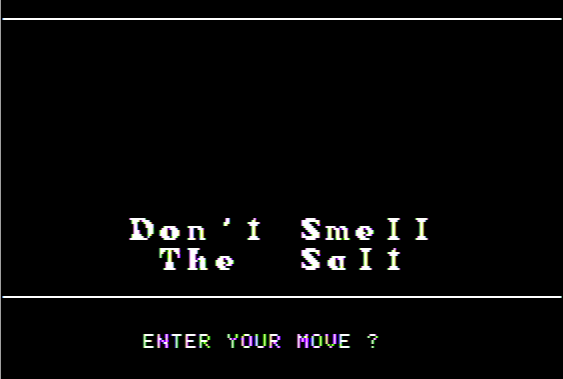

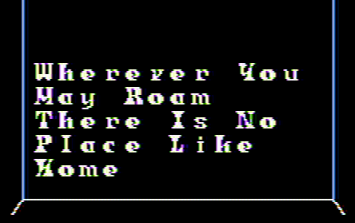

I’m guessing this is a meta-clue, essentially telling what the result will be when all the clues are put together; ex: “The First is Where I Live” giving a general location, “The Second Will Be Upon” being more specific. “And When I Get There I Will Watch Them Play” suggests the stone is hidden in a park, also suggested by this image:

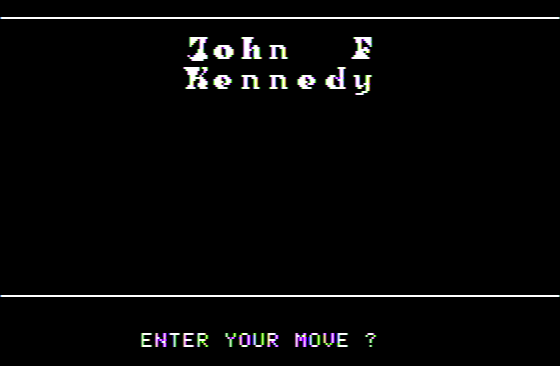

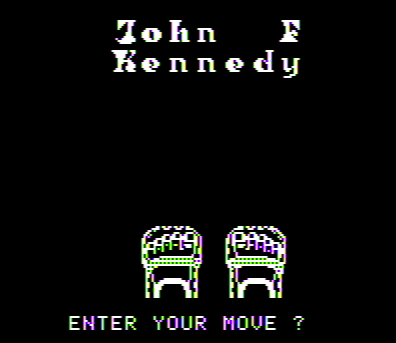

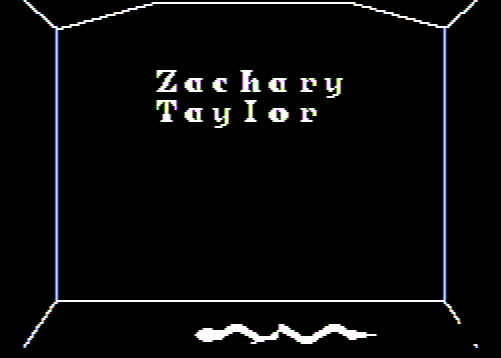

I found John F Kennedy a third time

suggesting it either a number is repeated three times or it’s a very important clue. I’m going with the latter theory for the moment. If we combine with the “Look to Albert for Help” from the very start, I think Albert may be the one in Washington D.C.

The podium and microphone (from my last post) suggest there may be a public speaking spot involved, perhaps a famous Kennedy speech location?

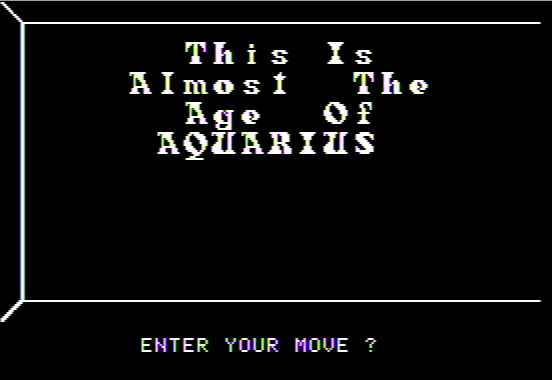

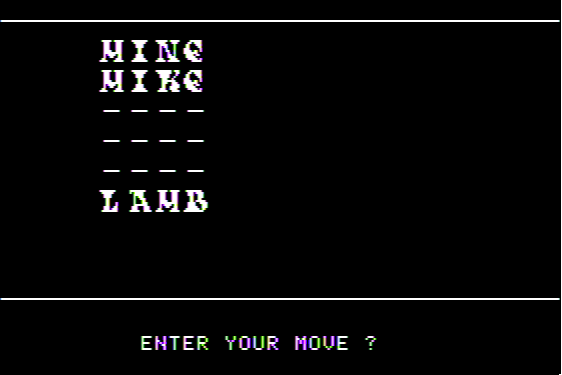

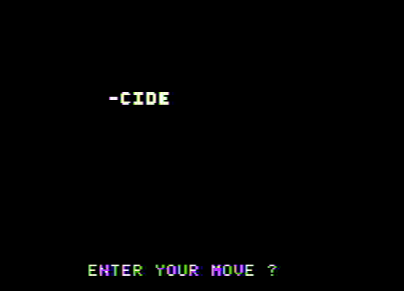

Here are the remainder of the clues I’ve found:

I’m ballparking based on clue density in places I’ve searched well that I have about half the clues in the game.

August of 1979 saw the release of Masquerade, a picture book that was also a puzzle with the solution being the location of a golden hare. It created both frenzy and scandal, but that is not our story for today.

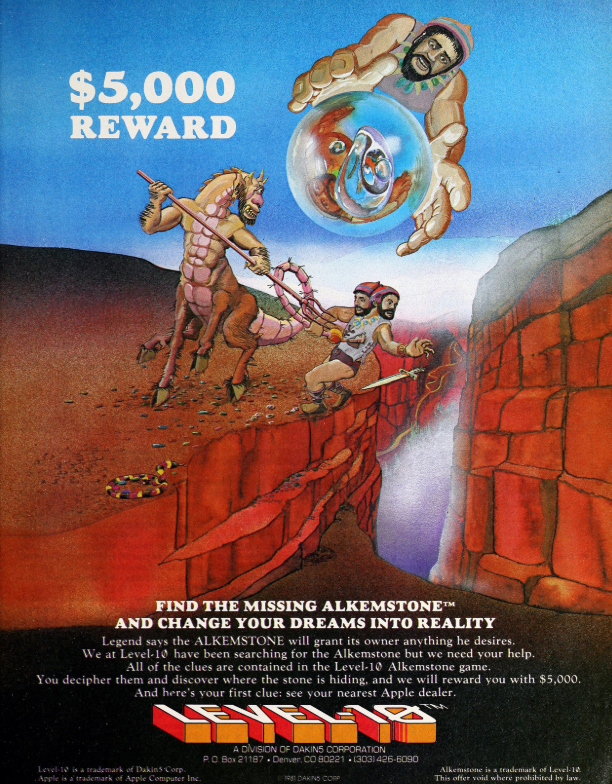

Two years later (before the Masquerade contest had even ended) a man named Gene Carr at a company called Level-10 made a treasure hunt of his own. Like Masquerade, it involved a treasure buried somewhere in the real world and clues to find it, but rather than hiding the clues in a book, he hid them in an Apple II game.

There were two ways to win:

a.) Find and deliver the physical Alkemstone, and describe its location.

b.) Send a detailed description of the Alkemstone’s hiding place.

In both cases, a particular lawyer (Ray Sutton) was in charge of verifying the winner. Mr. Sutton is still alive and has verified he never awarded the prize, and he has no record of the stone ever being found.

In other words, the treasure hidden 39 years ago is likely still in its original location, the hints locked in an Apple II game that barely anyone has played.

On an obscurity ranking system from 1 to 10, Alkemstone lands at about 8.5. Still, it has occasionally surfaced as a piece of gaming trivia — here’s John Romero tweeting about it in 2012 — yet even though it occasionally gets observed

Wouldn’t it be interesting if someone got busy on an old copy of the game and found the stone?

nobody seems to have picked up the gauntlet.

The buck stops here. Let’s try to solve the mystery.

…

Now, this is rather different than my usual playthroughs for All the Adventures, insofar as the end result of all this may involve unearthing a real item. I do want to emphasize that the Alkemstone as an object in itself is not considered valuable (unlike the golden hare); the potential money came from proving where it was. Additionally, despite the lawyer still being alive, the company that offered the prize is long defunct. That means there’s no money at stake, just historical interest.

I will state up front if by some happenstance I come to possess the stone personally, I will donate it to a gaming museum like the Strong. In the (much likelier) event it lands in someone else’s hands I hope they do the same, but I can’t enforce that.

And of course, the Alkemstone may be buried under a parking lot or lost due to some other circumstance.

So feel free to contribute any theories as I post clues, but keep in mind the above caveats. I won’t say it will end in disappointment because even if the physical stone is never found, the solution to the game in general has been a long-open question and would be an achievement in itself; there’s no maps or hints or walkthrough here to rely on.

…

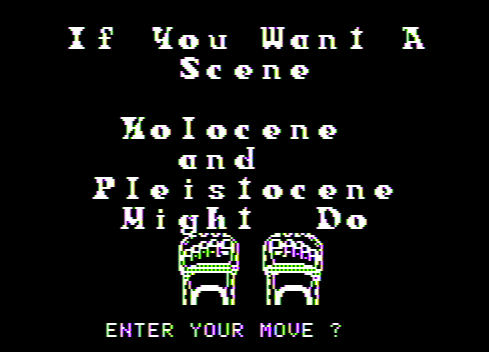

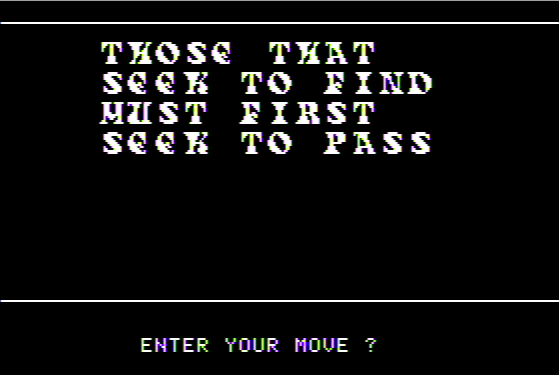

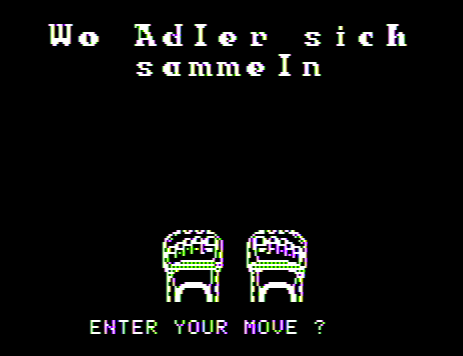

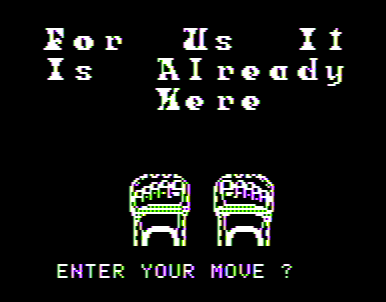

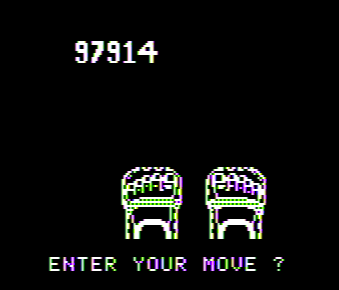

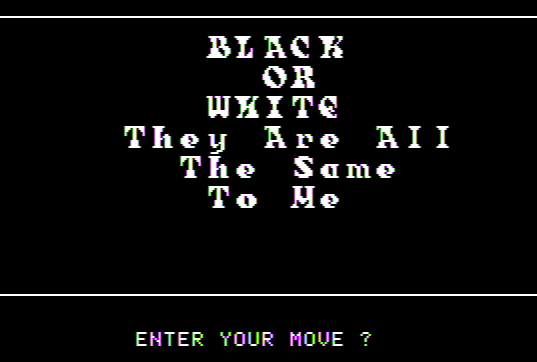

The first scene upon entering the maze; there’s no “hanging banners” style messages other than this one.

Enough preliminaries: what is the game like?

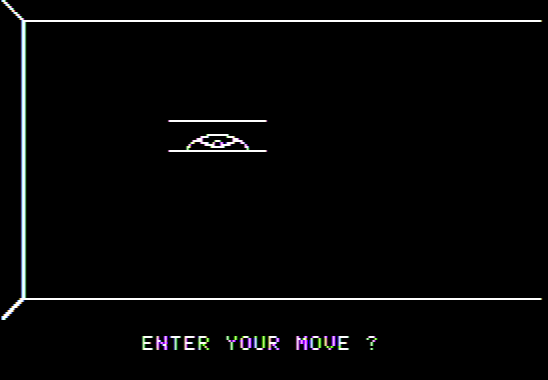

The snakes pass by at random.

Alkemstone adapts the 3D engine from Kaves of Karkhan into a pure-exploration game. There are no obstacles, unless you count illusionary walls and a very, very, large map.

Around half of the map; I still need to fill in a lot of the other half.

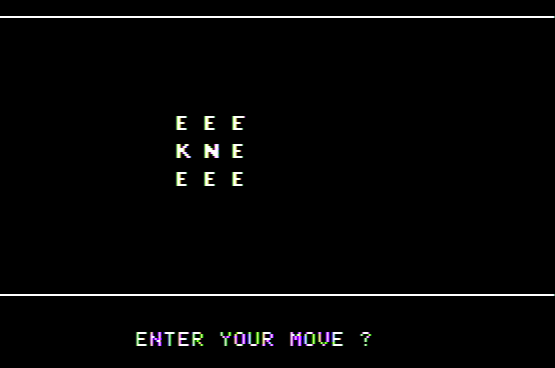

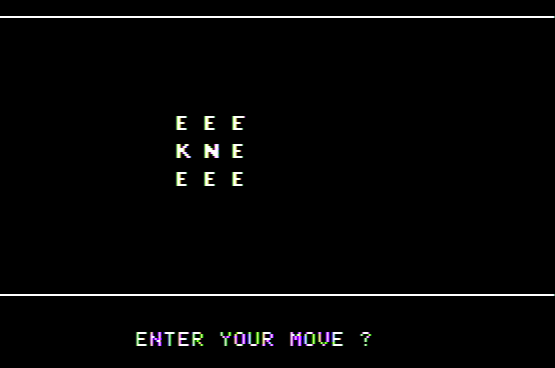

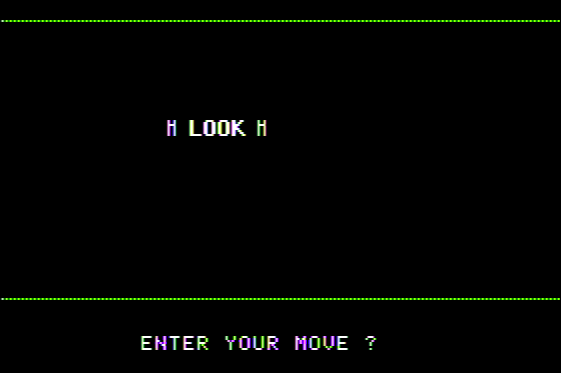

The maze is seeded with clues. You can find them on the walls

or you can find them looking up (tap U to look up)

or looking down (tap D to look down)

The clues are scattered everywhere; finding them all is partially a matter of just being thorough. Sometimes the clues are “solid” and will always appear, but sometimes they flash on and off, or only are visible 1 out of every 10 or so times looking at a particular ceiling. To give you an idea of how easy the clues are to miss: even though I have found 25 “clues” so far I am missing the two shown in screenshots on Mobygames.

I will say the maze is not randomized, and despite the manual’s claims to the contrary, the clue locations don’t seem to be randomized either. It’s still true more than one “walk through” is likely required to spot everything.

I’m going to try my best to sort the clues I’ve found so far by type, but these categories are arbitrary and may be misleading in terms of how the clues actually connect.

In case it’s important, I do have where I found them marked on my map, but I’d like to get my full map closer to completion before I share it.

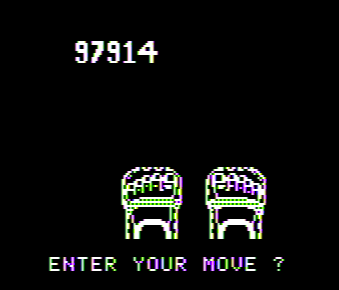

IMAGES AND SYMBOLS:

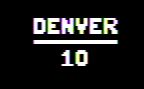

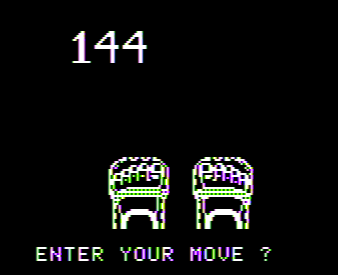

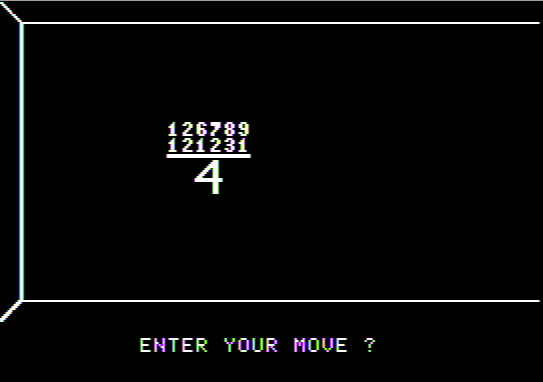

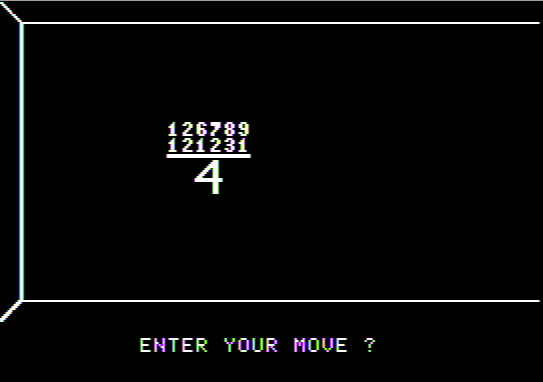

NUMERICAL CLUES:

MESSAGES:

This image also appeared on a wall. I don’t know if the duplication is redundancy to help keep from missing certain things or a clue.

THE TWO FROM MOBYGAMES I HAVEN’T FOUND YET:

…

While there are some obvious surface observations I could make, I’m going to save them for the comments. Just keep in mind the game was released in 1981 (late in 1981; the Nov-Dec 1981 issue of Computer Gaming World mentions it will be available by Christmas, and it has a trademark filing of November 12) so any events or media references to works 1982 or later won’t apply.

There is an online version of the game available, except it gets stalled when asking to flip the disk. There might be a button press in the emulator that will work, but I wasn’t able to play any further.

I wish I could say I had some grand strategy, but I pretty much just grinded until the game decided to show me a win screen.

The only thing I did do extra (and I’m unclear if this is really helpful) is I tried my best to go up rather than down. I used ladders and up-stairs when I saw them, but avoided holes in the ground and down-stairs when possible (it wasn’t always possible).

I honestly suspect the bier (the place where a coffin is placed before being taken to a grave, although it doesn’t look like that from the picture) might just pop up randomly when you’re far enough in the game.

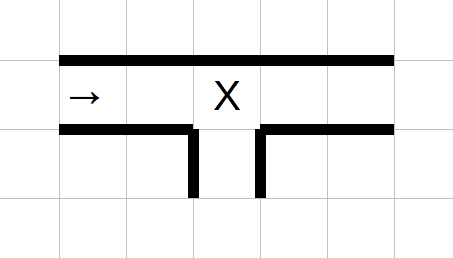

I did make some honest attempts at mapping, and it helped a little at the local level; within a particular area the level is at least somewhat consistent, and it’s possible to systematically eliminate corridors as you test them. One thing I only discovered very late is that encounters “eat up” the square of the map you enter, so if you successfully do an encounter, you “jump” to the next square. That means you may entirely miss a side path that would normally be in that square and you’ll only see the path if you turn back.

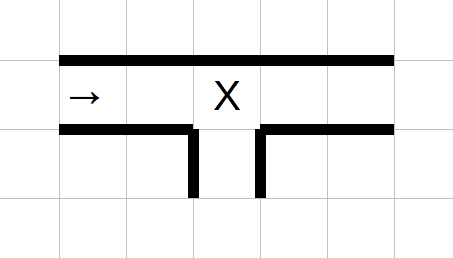

Above is a typical configuration. I was going “east” and I hit the spot marked “X” and there was a river of blood I used a plank to get by. In the process, I missed seeing the passage that went “south” and had to turn around and enter the X position to find it. It’s possible to “skip” the intersection multiple times if you keep finding encounters there.

One last discovery I made was regarding chests. I hadn’t been able to interact with them (“OPEN CHEST” didn’t work, and trying to use my thief or a hammer or anything like that led to nothing happening). I finally discovered just OPEN by itself works.

Another episode of Great Moments in Game Parser History.

Unfortunately, I discovered this when I nearly was at the end, too late to be useful; I had a method past every obstacle except, of all things, a walled-up corridor.

You’d think a hammer would help here, but no.

…

Just for reference, the only other games I’ve hit in my sequence so far I’d call roguelike-adventures are Mines and Lugi. While Kaves of Karkhan was bad for personal enjoyment, it’s still fascinating as an artifact of design. Some of the elements — like having a limited subset of available items, and randomized puzzle placement but consistent solutions — seem like they’d make a roguelike-adventure a success, but they fell down hard here.

First, keeping track of 10 characters and 10 items was excessive. It made getting used to the environment rough, and I only felt comfortable after about two hours of gameplay.

Second, it makes for overly simplistic gameplay when each puzzle boils down to finding the right object or character. This is similar to my complaints with Devil’s Palace and The Poseidon Adventure where the authors try for higher difficulty without an adequately complex world modeling system to match. By contrast, Lugi had some persistent effects (like being infected) and puzzles that needed to be solved with objects in combination.

Third, the map was too random to use geography in any rational way. To compare with Lugi again, in that game it was possible to encounter a puzzle in one location, find a helpful object in another, then loop back to the original location to solve it.

Fourth, the punishment of losing objects or characters for failed puzzle attempts was too harsh in context, and it was impossible to reliably survive a loss of resources without already knowing how to solve most of the puzzles.

Fifth, having almost no items found during the process of the game undercuts a lot of what makes an adventure game fun (having an adventure game without the ability to “increase power” with new discoveries is akin to an CRPG that doesn’t let you level up your character). Even an essentially item-less game like Myst at least contains a steady drip of new information and clues.

The only immediate “fix” I could see that would help the game without more extensive design changes would be to allow a lot more alternate solutions. As things stood I was jamming pipes with juggling balls and walking on lava with buckets, and not because I was being creative; they were the only solutions I could find via brute force testing everything I had.

We’re going to have at least one more adventure-roguelike in 1981 — Madness and the Minotaur — at which point I’ll try a grand recap and armchair design of How to Make Such a Thing Work (or possibly, instead, a cautionary warning that such experiments are best left in the early 80s).

Long before we get to that, we have another game from Level-10 that re-uses their 3D engine for a much different game; one only comparable to a handful of computer games across history, and with a mystery that has never been solved.

Five years ago when I was writing about Treasure Hunt (1978) I remarked on a lack of deviation from adventure-genre norms; the Crowther/Woods version of adventure was essentially so good (and already in computer form) that most that immediately followed just copied the model, rather than approach their own way.

CRPGs, by contrast, were trying to adapt a tabletop game, and it wasn’t terribly obvious what form an adaptation would look like, so there were lots of early experiments.

Kaves of Karkhan feels like a game from a parallel universe where the standard text adventure format never dominated. I reckon the reason why it exists in the first place is that it comes from a series which started with a CRPG: Dragon Fire (1981), which was covered by The CRPG Addict in detail here.

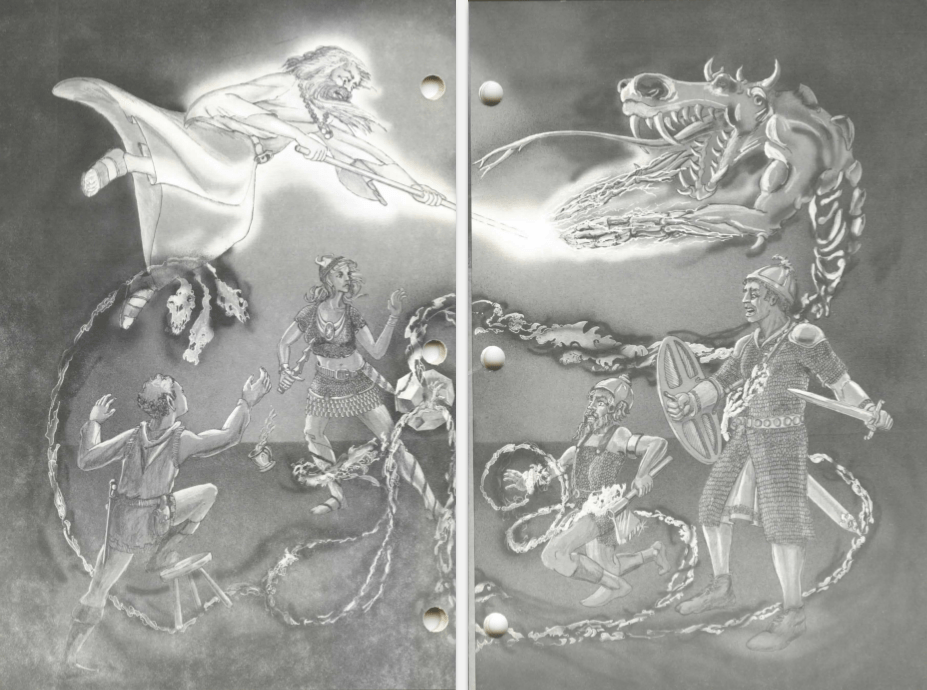

According to the manual, the second game, Kaves of Karkhan, uses the same characters as the first: an unnamed warrior, dwarf, huntress, and elf. (The first game had a wizard but you can’t control him in this game for reasons you’ll see in a moment.) The manual tries hard to build lore around these characters, even though they are unnamed:

There is little traveling in this time before the harvest, and a new face arouses much suspicion. Some say the barbarian seeks revenge upon a man with a quarter-moon scar on his left cheek. Others say he’s a professional bandit specializing In the exotic: the left hoof of the centaur, the lost crown of the Faerie King, the eye of the stingbat, and the like. And still others say he seeks to give up his present occupation as fighting man and find something more peaceful, perhaps as an artisan’s or baker’s apprentice. A few insist he flees memories of a lost love.

The story starts directly after the first, where the party defeated an evil dragon and received bucketloads of treasure. The dwarf is busy showing off in a tavern, including a jewel he found “outside one of the rooms on the third level”.

A hairline fracture suddenly appeared in the jewel’s surface.

The dwarf leaned forward anxiously. The crack seemed to be branching off, dividing, but silently. He was amazed. His jewel was crumbling right before his very eyes, but completely without sound.

A shadow suddenly obscured the crack. The dwarf looked up, but there was no one standing over him. He looked down and the shadow was still there, in fact had spread; the shadow crept across the surface of the jewel as If it were liquid. Upon closer examination the dwarf could see that the shadow had issued from the crack.

The gem was a container for a demon named Maldameke who is now breaking free. The wizard manages to contain the demon, for now

“Take the jewel . . . the pieces . . . return them . . . to Maldamere’s home … the bier … the top of the mountain … even one piece … will draw him … back there … trap him … in the Kaves of Karkhanl Hurry! Hurry! Cannot … hold him … long … but beware … beware … his influence … is still … felt … in those underground … realms … “

but the rest of the party now needs to “find your way through the maze of hallways within the crags of Karkhan, solve the traps, and then deliver your piece of the gem into the bier at the top of the mountain”. Each of the four original characters (warrior, dwarf, huntress, elf) picks a team to take along. In actual gameplay, I found no difference between the choice of main character (and you have no interaction with the characters you don’t pick), so the “team” is what’s important.

Yes, ten characters, and you need to keep track of their names and occupations (only in the manual). I used a spreadsheet.

After starting the game, you are told to open the entry doors you must solve an anagram.

It’s always two four-letter words jumbled together, but the words used are random from a fixed list. This one was STEMROPE. There’s lots more valid two word combinations here (like MORESTEP or MOSTPEER) but none of them work.

Then you’re dropped into a randomly generated first-person perspective, and the pain begins.

This incidentally means Kaves of Karkhan is the first 3D-perspective adventure by someone other than Med Systems.

The game moves sluggishly (especially at authentic 1981 Apple II speeds!) and the maze is so random it seems to have no logic at all. You can go down a dead-end hallway only to turn around and find a stairway up has appeared.

The main “gameplay” is a set of randomly appearing traps and encounters, and again, there seems to be no logic to their placement or appearance. A hall with a chasm one moment might turn into quicksand in another. (Only after defeating the obstacle the first time, though — you can’t switch which obstacle you’re looking at just by going back and forth.)

In order to get by an obstacle, you have to type a two-word command. Most of the time it’s USE (character) or USE (item) although there are a few exceptions. Quite often you can lose an item or die by getting it wrong; here’s a transcript of the water obstacle above.

?USE PLANK

NOTHING HAPPENS

?USE NET

NOTHING HAPPENS

?USE BUCKETS

NOTHING HAPPENS

?THROW PLANK

NOTHING HAPPENS

?USE ALANA

ALANA WAS JUST KILLED BY THE WATER

?USE JUG

YOU THROW THE JUG IN. IT FLOATS! EACH CREW MEMBER USES IT IN TURN TO CROSS THE WATER. ALL GETTING QUITE WET.

Alana was my (now-expired) sorceress. I quite often would burn through my entire party (ending the game) while trying to get by a single obstacle.

Occasionally there is enough logic to passing an obstacle that I was able to do it first try; when encountering some weeds I tried USE MILES, my farmer…

…but for the most part, on each obstacle, I had to lawnmower down through my entire list of available objects and people.

Here I am getting by a mystic portal by using THROW BUCKET.

While there are some multiple solutions to puzzles (THROW SWORD also works on the above puzzle), I knew if I lost a character or item I could potentially get stuck, so I made generous use of save-states while I took notes on how to defeat each obstacle. My “favorite” piece of absurdity was using my acrobat to defeat a lake of fire.

Oh yes, the game is timed. If you switch emulator speed to “fastest” in order to avoid sluggish walking you get an immediate game over.

I’ve yet to beat the game — I keep wandering the maze in circles — and I may soon just call this one finished. I will still make one more post, because this game represents another stab at the ultra-rare adventure-roguelike genre (where puzzles form the primary gameplay, yet the environment is still highly generative).

…

I don’t know who to credit for this game other than the company (Level-10). The previous game in the series (Dragon Fire) was made by Rodney Nelsen. The follow-up game (which we’ll get to next, but is very different) was made by Gene Carr. I think it more likely Gene Carr was the author of Kaves (the 3D engine was in the latter game but not the former); however, at the moment I have no proof.

The one person involved with all three games was Steve Rasnic Tem, who did the manuals. At least with Kaves, the backstory is stronger than the game itself! Steve Tem later went on to write quite a few books and win a World Fantasy Award for a novella he co-wrote with his wife, Melanie Tem.

Here’s one last excerpt from the manual to close things out, for now:

Looking around him, once again the dwarf felt vaguely puzzled by the variety of types in the human community. No other race to his knowledge possessed such a range. Packed elbow-to-elbow in the tavern’s central room he could see a skinny youth carrying a rope looped over his shoulders, a short man carrying three companions twice his size, a tall man with his face covered by gray gauze — all shapes and sizes of humanity. The dwarf wondered how humans must keep track of them all; it seemed very confusing to him.