Dante’s Inferno was a type-in by Gerard Bernor printed in the January 1980 issue of Softside which tasks you with stealing your contract with the devil from Hell itself. (It states a 1979 copyright date in the source code, so 1979 also works as a date, but I’ve found no evidence of a commercial release prior to the magazine appearance so I’m listing this game as 1980.) The print copy called it a “CompuNovel”, a term used very sporadically elsewhere (ex: page 5 of this February 1980 issue of Softside in an ad for Lost Dutchman’s Gold) and one that died out by 1981.

Rather like Quest from 1978, it has no parser, just navigation: specifically the keys F, B, L, R, U, D for Forward, Backward, Left, Right, Up and Down. This is *not* a relative position game, though (that is, “left” and “right” don’t change based on which way you’re facing) – these directions can be treated like the regular north/south/east/west on a map, which is good, because the game is essentially a large maze.

The game uses pauses for dramatic effect, starting with the screen below:

Keypresses don’t work for a few seconds; you have to actually wait for the first location to appear.

I did find this more enjoyable than Quest, insofar as that the genre of a journey through Hell made the idea of a torturous labyrinth with slightly random layout thematically appropriate. There were a lot of “dead ends” (an easy way for the author to add map locations without having to add extra room descriptions) and there was the usual “going one direction and then going back the opposite way may not take you where you started” business, but all this worked well with the atmosphere.

After about 30 minutes of wandering, I found the “records” and was able to pick up a box of contracts. (Not just mine, the whole box! Guess a whole swath of people are gonna escape the devil.)

But then, a twist!

Rather by accident, Dale Dobson over at Gaming After 40 had an even better experience than intended. At the moment this happened, the TRS-80 speaker let out a “horrendous, screechy white noise” that caused him to jump out of his seat. Unfortunately, this was just a bug. Otherwise it would mark the first use of a sound cue in an adventure game.

A bit more navigation is required to find a different records room, where the contracts have been moved to. (It’s a little unclear why the incubi leave the main character alone otherwise; maybe in the end they appreciate a bit of mischief.) Unfortunately, trying to then go back the way you came has the route blocked off (either by a narrow hall where you can’t carry the contracts, or Satan himself).

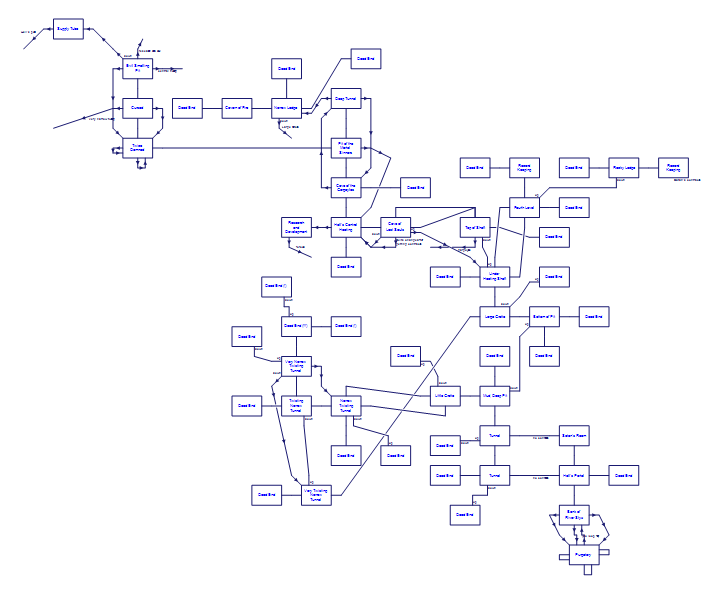

There’s a little more drama after that point: the route you then need to take is down an “evil smelling pit” (in the upper left corner of the map above). However, the “cave of lost souls” room which was on the way seemed to have all its exits reconfigured, so I needed to find an alternate route.

My move count was high, but I was trying to do very careful mapping.

This game hit over its weight class. The narrative frame made what normally would be the drudgery of mapping into a paranoid journey. I guess the lesson is: if your gameplay is going to be minimal, pick a theme that matches.

This glorious picture is from the magazine. I appreciate the “S” on his necklace.

no comments in 5 years. Dang. I played this thru to the end because it is historically significant.

it turns out that being able to get and use objects and interact with the environment is essential to making a game that feels…interactive.

while it has no verbs and no nouns and is ultimately all a big mapping exercise in a map that seems large unless you omit all the dead ends — there are some actual descriptions in here. If course, if that makes you want to interact with anything, too bad.

Some people don’t want to part with an examine, describe or look at abillity. I thought they were being rigid or harsh, applying later standards to times when there were extremely tight resource restrictions limiting what could practically be done.

but playing games without it, where you are picking up and using objects with no description is not really “almost as good”..

then you delve back in history and say “you don’t like getting and using objects with no descriptions, how about no objects and no verbs?”

how much can you remove and still have just a more simplified something? What is a minimalist aethetic?

somewhat more than this.

I think an interesting contrast if you haven’t played it would be The Fire Tower

https://ifdb.org/viewgame?id=fcm1ikz9ttr6i99a

it’s a modern(-ish) “just explore” game but it include verbs other than walking around and more vivid writing and so forth and gives an impression what the late-70s-early-80s “just explore” games were missing

Interesting. Of course, the early, tiny games had so little memory to work with that they barely even had text, often, there’s not enough to really assess writing quality, let alone generate rich atmosphere.

So probably that makes an important difference.

I should say that the theme here was epic, and there is a story / plot / goal / puzzle(s), just implemented in a way that there are no verbs or nouns.

One might imagine that the directions here, Forward, Back, Left, Right, Up, Down might be used in some CYOA-type ways, but they are all purely directional.

Thanks for the recommendation. I’m a bit fixated on truly old-school works right now, but modern works are important.

The aesthetic of extremely sparse descriptions seems to have its ardent minimalist adherents, there seem to be a good number of people doing work that suggests Scott Adams classics were the peak of the art form for them — but not cutting off the hands of the player and implementing no commands but walking.

I don’t regret spending time on it, but it makes me flash back to those days and realize what excited me so much about the idea of a text adventure, with limited exposure, I managed to convince myself that you could do anything in them. Ironically, the first I ever saw was “House of Seven Gables”. With only several minutes playing with it, I didn’t realize how limited it actually was, and wanting to be able to play text adventures was now an additional reason I wanted to get a computer…the first games I stayed in love with after actually getting to know them were indeed Scott Adams…

As someone who often wondered “Why are so few people willing to give the older games a chance?” actually trying to play them as intended (except with the help of Trizbort) is illuminating. Wandering around mapping mazes, out of context of other compelling content, is boring. I forgot what a high percentage of one’s time with these works were likely just that.

the game I’m playing right now has the super-minimalist style (“YOU ARE IN A DEN. YOU CAN SEE: A DESK”) but manages to be fairly vivid just from the layout and accumulation of scenes and also has no mazes

I don’t think I’ll be posting until tomorrow (I’ve been managing something like 5-a-week recently but I still need some off days) but you might be interested

Thanks for the walkthrough. Very helpful. I’ve made a new version for the TRS-80 MC-10, which your map helped me to debug. By any chance anyone know anything about the author? Like where he was from.

I do not, alas. There are more magazines scanned since last I played this so it might be possible to rustle something up.

I actually looked into this a bit at some point, as I found the game interesting, and my notes say:

May be the same guy as Gerard E. Bernor of Tampa, Florida, 1934-2001. He was listed as running a company called BC Creative Enterprises along with Kenneth Cline in Tampa circa the early 90s, and popped up a few times in mid 90s PC magazines as a creator/distributor of custom fonts (you can still find references to some of these online today).

It’s a very uncommon name, and the combination of being involved with computers, his relatively mature age at the time (fits in well with the tone of the game), and the fact that Florida was one of the early TRS-80 scene hotbeds, mainly thanks to the influence of Scott Adams, leads me to believe that there’s a decent chance it was him. Who really knows, though.

Fun facts: Softside mistakenly listed him as “Gerald” a couple of times, and the game was actually translated to French in 1983 by Claude Picard as “L’enfer de Dante” for the Belgian DAI computer. The BASIC code for it can be seen on Bruno Vivien’s ParaDAI website.

Thanks Jason. I have also made a version of Artic Adventure, with the help of another of your posts. I found a weird bug in my ported code (not sure if it is in the original– I couldn’t get it running using a TRS-80 emulator). If you type SAY COAT right at the beginning it would run the win game routine. Might be a result of my fiddling with the SAY routine, but it could be in the original source (probably not the 2021 version).